Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Michael Oakeshott (1901-1990)

Alistair MacFarlane considers the modes of life of a conservative philosopher.

Michael Oakeshott, like Ludwig Wittgenstein, is a philosopher’s philosopher. He had a unique point of view, and a coherent way of looking at life, clearly expressed in wonderfully elegant prose. Oakeshott was also utterly indifferent to fashion in academic, political and philosophical life, and pursued obscurity to a point of near public invisibility. On his death, the local pastor who was due to take his funeral service was astounded to read in his Daily Telegraph of 21st December 1990 that he was soon to bury “the greatest political philosopher in the Anglo-Saxon tradition since Mill – or even Burke.” The Guardian called him “perhaps the most original academic philosopher of this century”; and in the Independent his writing was compared to the essays of Montaigne, which would have greatly pleased him. When reporters asked his neighbours about him, all they learned was that he had rebuilt, with his own hands, the cottage where he lived, and that he drove a very old sports car. As for where he came from, or what he had done for a living, they had no idea.

The Telegraph’s comparison of Oakeshott with both Mill and Burke is significant, because Oakeshott suffered a great misfortune: he was a liberal little ‘c’ conservative whom Britain’s Conservative Party tried to claim as one of their own in an attempt to acquire intellectual respectability. He made his personal opinion about that clear by refusing the offer of Companion of Honour made by the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. In his own words, to be conservative was to “prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.” It was an attitude to life, not a political label.

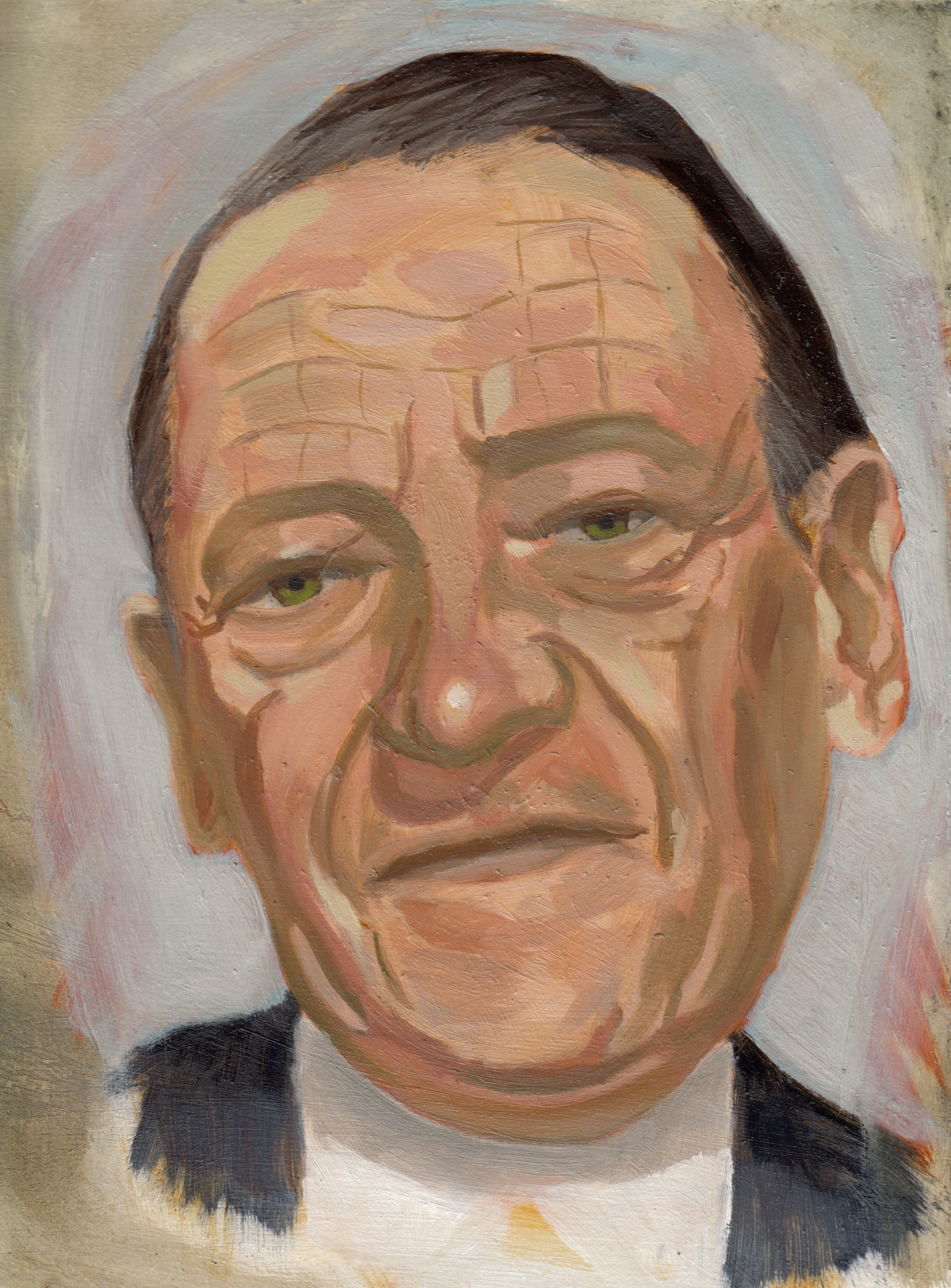

Michael Oakeshott

Life

Michael Joseph Oakeshott was born on 11th December 1901 in Chelsfield, Kent. His father was a civil servant in the Inland Revenue Department, and played a prominent role in the socialist Fabian Society. His mother Frances was a vicar’s daughter who trained as a nurse, and ran a small military hospital during the 1914-18 war. He was the second of three brothers.

Oakeshott read History at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. On graduating, he was elected to a fellowship. Outraged by the political extremism that was engulfing Europe, he renounced his pacifist principles and joined the army in 1941. An attempt to join the Special Operations Executive to become a spy was rejected on the grounds that his quintessential Englishness would make it impossible for him to work undercover. Undeterred, he managed to join an intelligence unit linked to the SAS, and saw active service, though not in the front line. After the war he returned to Cambridge for two years.

Following a brief spell at Nuffield College, Oxford, Oakeshott was unexpectedly appointed to succeed Harold Laski at the London School of Economics. The appointment outraged most left-wing academics because it was such a blatant abuse of the power of appointment by the new Conservative government. The LSE was famous for its long association with the Fabian Socialists since the days of its founders. Although his appointment was widely regarded as a scandal, he was unperturbed, accepted it, and held the position of Professor of Political Science there from 1951 till his retirement in 1969. During his time there he produced, among other fine work, his famous collection of essays on Rationalism in Politics (1962). It provides a devastating rebuttal of the mean-spirited and resentful criticism to which he was subjected. In his inaugural lecture he courageously defended his view that the prime duty of a political philosopher was not to change the world but to seek to understand it. It was not his job, as he saw it, to propagate narrowly conceived ideological programmes aimed at radically transforming the human condition.

Although the liberality and humanity in his writing is attractive, Oakeshott was not an admirable human being. Rather, he was an unabashed libertine who treated many women with cruelty whilst professing to admire and respect them. He was married three times. His first marriage in 1927 was to Joyce Fricker, a graduate of the Slade School of Art, with whom he had a son, Simon. After it ended in divorce in 1938, he married Katherine Burton. This fared better, but they divorced in 1955. His third and most successful marriage was in 1965 to Christel Schneider, an abstract artist. This lasted until his death, since they led largely independent existences.

Philosophy

The organising principles behind Oakeshott’s philosophy are based on his concept of modality, and are introduced in his first masterpiece, Experience and Its Modes (1933). For Oakeshott, a mode is a particular consistent way of looking at the world, emerging from a settled direction of attention. Modes include morality, science, art, religion, music, poetry… and, above all, the practices of everyday life. Each mode represents a coherent area of human achievement, and none can claim to be superior to any other. The possible number of modes is limited only by our imagination. We master a mode by sustained engagement and practice, leading to a body of experience that cannot be reduced to formulaic procedures, nor simply characterised in terms of goals. Oakeshott’s bêtes noir were the Rationalists who thought that everything could be reduced in such ways.

Oakeshott’s work bears strong affinities with that of the later Wittgenstein. Some would claim that Oakeshott’s is the more humane and accessible approach. His view of everyday practices is very different from Martin Heidegger’s view of them, but in the same spirit of reaction against a narrow way of understanding. In terms of traditional philosophical categories, Oakeshott could be regarded as an Idealist – the idea that reality is fundamentally mental in nature – since for Oakeshott a description of reality had to provide more than “an unearthly ballet of bloodless postulates.”

Modes of Behaviour & Modes of Experience

Oakeshott’s philosophy focuses on part of our daily lives that is so familiar we normally give it little attention: our ability to switch between specific ways of acting. We have evolved over millennia as a species, and learned over decades as individuals, to be able to cope with different circumstances. This capacity is a necessity for survival in a complex and unpredictable world. Our earliest ancestors had to constantly switch between hunting prey and fleeing predators, between obtaining food and preparing it, between life as individuals and life in a community. Later ancestors had to reconcile their daily lives in a variety of occupations with the sudden, violent upheavals of wars and other calamities. Such modes of behaviour are specific forms of organizing our mental, physical and social ways of acting in order to achieve specific goals or to cope with specific circumstances. In Experience and Its Modes Oakeshott discusses in detail historical experience, scientific experience, and practical experience.

The modes are best appreciated by considering extreme examples. So imagine you’re a world-class athlete taking part in an Olympic final. How did you get there? By extensive and demanding physical training, which developed your great natural talent into a superlative specialised skill. By rigorous mental training, which enables you to shut out all distractions, and to focus, briefly but totally, on executing your skill when required. And by organising a very specific set of your mental, physical and social (working with your coach) ways of acting in the world. In short, you’re able to switch into and out of a very specific mode of behaviour. Equivalent modes are exhibited by virtuoso musicians performing in concert; by exceptional scientists making great discoveries; and by great philosophers working out new ways of looking at the world. Few of us can be Olympic medallists, or Nobel prize winners, or join the pantheon of great thinkers and artists: but all of us, to greater or lesser degrees, must be able to switch into and out of modes of behaviour. To achieve out-of-the-ordinary things, we have to focus and co-ordinate all our relevant resources and exclude everything irrelevant.

On Human Conduct

Oakeshott’s second masterpiece, On Human Conduct (1975), follows from and massively extends the ideas developed in his first. It is in the form of three lengthy connected essays. The first deals with the theoretical understanding of human relationships, and further develops and refines the ideas of modes of experience. The second, entitled ‘On the Civil Condition’, extends his concept of modality to what he calls ‘civil association’. The idea of a civitas or civil society as a rule-articulated association of human agencies runs through the whole book like a golden thread. The final essay, ‘On the Character of a Modern European State’, traces the evolution of the European state from medieval times to its modern form. The whole book reads like a long, elegant conversation, albeit one which demands careful and unremitting attention.

Oakeshott’s last books published during his lifetime were On History (1983), a collection of essays summarizing his philosophy, and The Voice of Liberal Learning (1989). For almost all his adult life, Oakeshott kept a detailed personal journal, from which selections have also now been published as Notebooks, 1921-86 (2014). This is a collection of miniature essays, observations and aphorisms on his philosophy and his private life. It’s an astonishing document. Although no mention is made of wives, friends, or relatives in it, it’s so revealing in parts that it’s hardly believable that he would have wanted it published, rather than simply made available to researchers.

Last Days

After retirement from the LSE, Oakeshott retreated with Christabel to Langton Maltravers, not far from the Purbeck quarries on the Dorset coast. Here he purchased two adjacent derelict quarrymen’s cottages, which he renovated and converted himself. While Heidegger also extolled the philosophical interest of manual work, among great philosophers only Oakeshott seems to have engaged in it.

Towards the end of his life he developed cancer, although he concealed it from his wife and friends until the very end. In mid-December 1990 he became increasingly ill, and died around midnight on 18th December, just a week after his eighty-ninth birthday. He is buried in the cemetery of the village church in Malton Travers. A close friend later remarked that he would have enjoyed his funeral as there was nothing remarkable about it.

Legacy

Oakeshott’s philosophical approach has great humanity and breadth, and relates closely to the familiar practices of everyday life. Reading him after struggling with the complex intricacies of some modern writer’s approach to, say, the philosophy of mind, is like stepping out of a crowded underground carriage in the rush hour into a sunlit, open meadow. We need philosophy to be accessible, uplifting, understandable, enjoyable, and practically useful. Oakeshott’s great legacy is to show that this is possible.

© Sir Alistair MacFarlane 2017

Sir Alistair MacFarlane is a former Vice-President of the Royal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor.

Correction

This article originally appeared with this picture of philosopher Maurice Cranston instead of Michael Oakeshott. This mistake has been corrected.

Maurice Cranston 2017 portrait by Darren McAndrew