Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

In Thoreau’s bicentenary, Martin Jenkins looks at the famous American eccentric.

A few years ago I went into a bookshop to buy a copy of Thoreau’s Walden (1854). I couldn’t find one, but the assistant could: in the fiction section. This may reflect the difficulty of classifying Thoreau. Was he a nature writer, a poet, a travel writer, a political thinker, even a philosopher – even all of these? Perhaps; but not, I am certain, a novelist!

Thoreau’s works do not help to classify him. He wrote widely on a range of subjects. He only published three full-length books, but wrote numerous essays and lectures, and he kept a journal which ran to two million words. However, two works stand out philosophically: Walden and the essay Civil Disobedience (1849).

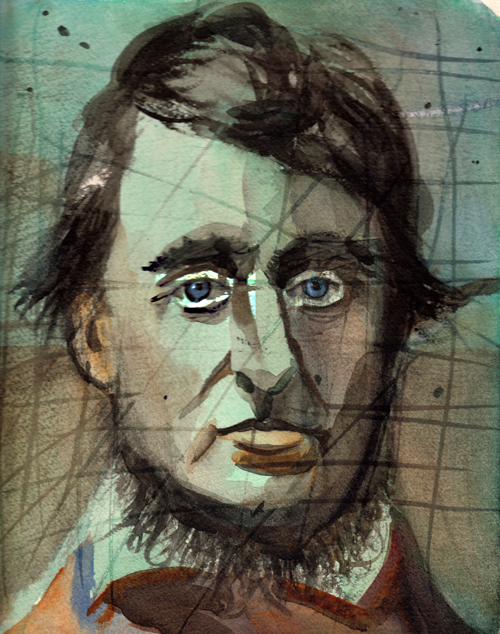

Henry David Thoreau portrait by Darren McAndrew 2017

Life

David Henry Thoreau was born in Concord, Massachusetts, in 1817. (He called himself Henry David from 1837, the year he started his journal. Both may be seen as expressions of his individuality.) His father was at first a farmer; but also ran a grocery store, worked as a teacher in Boston, and then returned to Concord to run the family’s pencil factory.

Thoreau was sent to Harvard in 1833. He undertook more than the required curriculum, and graduated in 1837. Returning to Concord, he took a job in his old primary school, but resigned rather than flog his pupils. Subsequently he opened a secondary school with his brother John.

About this time Henry was attending meetings of the group loosely known as ‘The New England Transcendentalists’ at Ralph Waldo Emerson’s house in Concord. This group was united more by interests than by ideas: the one thing that they agreed on was opposition to slavery. However, they managed to create a magazine, The Dial, in which they expressed their various ideas, and to which Thoreau contributed more than thirty essays and other works.

In 1839 both John and Henry Thoreau fell in love with Ellen Sewell. She rejected both their proposals. This is the only known romantic attachment in Thoreau’s life. In 1841, John’s ill health resulted in the closure of the school; and in 1842 John died of tetanus after cutting himself shaving. Henry was devastated and for a while suffered a psychosomatic paralysis.

As early as 1837, Henry Thoreau had improved the graphite used in the family firm’s pencils. In 1844 he developed an improved drilling machine for the pencils, as well as pioneering shades of graphite. In the same year, when Emerson could not get a single Concord church to offer him space for an anti-slavery lecture, Thoreau organised the use of the courthouse. In 1850, when someone was needed to go to recover the body and manuscripts of Margaret Fuller after she drowned in a shipwreck, it was Thoreau who undertook the job. So Thoreau was an eminently practical man, and could have been a commercial success. But he chose a different road, and spent most of the rest of his life relying on odd surveying jobs and work as a handyman.

In 1845 Thoreau began to construct a cabin in the woods by Walden Pond, about a mile and a half from Concord. He moved in on July 4th, and remained there until 1849. He was not a hermit, nor did he set out to be self-sufficient: by his own admission he spent a lot of time with friends, and at his family home, and often had meals there. Indeed, the most famous incident of his life occurred because he went into town to collect a shoe repair from the cobbler, whereupon he was arrested for non-payment of his poll tax and imprisoned for a night, being released after a friend paid it for him. Thoreau refused to pay the tax in protest at the state’s collusion with slavery in the Southern states.

Anarchy In The USA

The outcome of this experience was Civil Disobedience, which opens with a statement of his political philosophy:

“I heartily accept the motto, ‘That government is best which governs least;’ and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe – ‘That government is best which governs not at all’; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have.”

This is, of course, anarchism; but, as the last phrase shows, Thoreau believed that human beings had to become worthy of it.

In the meantime, how should those who are worthy of it act towards the state as it exists?

Thoreau’s answer is in one sense complex but in another sense simple: the individual must follow their own conscience, and refuse loyalty and obedience to the state which lacks moral virtue. Slavery, he says, is not maintained by Southern slave-owners, but by Northerners who tolerate it in the interests of maintaining the state.

However, Thoreau is not a rampant individualist. Having refused to pay his poll tax, he writes: “I have never declined paying the highway tax, because I am as desirous of being a good neighbour as I am of being a bad subject.” He insists on being a good member of the community – just not of the state. After being released from prison, he joined a party who were going out to pick huckleberries (“who were impatient to put themselves under my conduct”), and two miles outside Concord “the State was nowhere to be seen.”

Civil Disobedience is arguably the most influential of Thoreau’s writings. Reading it convinced Gandhi to develop his theory and practice; and maybe Gandhi, in naming his method satyagraha, or ‘truth-force’, came close to summarising Thoreau’s philosophy.

Into The Woods

If Thoreau’s stay in the woods was not an exercise in self-sufficiency, what was it?

It was an exercise in self-exploration. “Be a Columbus,” Thoreau wrote, “to whole new continents and worlds within you, opening new channels, not of trade, but of thought.” If Civil Disobedience explores the proper relationship of the individual and the state, Walden asks how the individual should properly relate to himself, others, and the world in general. How do we perfect ourselves, and thus become worthy of the ideal state? And to answer that question for yourself, you need to know who you are as an individual.

In Walden’s long opening chapter Thoreau mounts a critique of modern life and how it generates ‘needs’ (for ‘better’ shelter, clothing, food, etc) which are not needs at all. He memorably describes modern heating as being “cooked, of course à la mode.” He also has no time for the “need for speed” and is unimpressed by the railroad. He writes:

“Our inventions… are but improved means to an unimproved end… We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate… As if the main object were to talk fast and not to talk sensibly.”

Having expressed his dissatisfaction with the contemporary world, Thoreau moves on to put forward the alternative he discovered by living at Walden.

Thoreau was not living there to avoid human company. He begins the chapter ‘Visitors’ thus: “I think that I love society as much as most, and am ready enough to fasten myself like a bloodsucker for the time to any full-blooded man that comes in my way.” He claims to have had up to thirty people in his hut at one time; his circle included thinkers such as Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Margaret Fuller. But most of the ‘Visitor’ chapter is concerned with one man, a Canadian woodcutter. Thoreau clearly enjoyed his company, and “did not know whether he was as wise as Shakespeare or as simply ignorant as a child.” The woodcutter did not want to change the world but knew how to live contentedly in it; he had some thoughts, but not great ones: he was, Thoreau says, humble without knowing what humility was. It is difficult to imagine a greater contrast to the high thinking of the Transcendentalists; but not hard to understand why Thoreau might have preferred the woodcutter.

This theme of company is continued in the chapter ‘Former Inhabitants’, in which Thoreau communes with the memory of people who formerly lived nearby: two slaves, a coloured woman, a potter, a ditcher, a tavern-keeper. This is Thoreau’s history of Concord: not its great men, nor “the shot heard round the world” but the humble people forgotten except in folk memory.

Thoreau had a great deal of solitude at his hut. Perhaps living there enabled him to ration his human contact, giving him time to explore himself, to encounter nature more directly, to meet and talk with people outside his usual circles, and most importantly, to think. “Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth,” he writes, recognising that truth is what human beings often do not want. On that note he creates a brilliant simile for how his book will be received by comparing it with the ice from Walden Pond: “Southern customers objected to its blue colour, which is the evidence of its purity, as if it were muddy, and preferred the Cambridge ice, which is white, but tastes of weeds.” For Thoreau, the truth is discovered by looking beyond appearance and testing reality.

Thoreau is often regarded as a ‘spiritual’ writer. But as has been shown, he was a practical man, and towards the end of Walden he brings together the search for truth and practicality:

“Say what you have to say, not what you ought. Any truth is better than make-believe. Tom Hyde, the tinker, standing on the gallows, was asked if he had anything to say. ‘Tell the tailors,’ said he, ‘to remember to make a knot in their thread before they take their first stitch.’ His companion’s prayer is forgotten.”

(The last sentence reminds us that Thoreau was possessed of a dry humour. For another example, “Some circumstantial evidence is very strong, as when you find a trout in the milk.”)

Out Of The Woods

Replica of Thoreau’s cabin in the woods

© RythmicQuietude 2010

Thoreau left the woods perhaps because Emerson wanted him to look after his house while he was on a lecture tour; but his own explanation is that “I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there” (Walden); or, “I do not know what made me leave the pond. I left it as unaccountably as I went to it. To speak sincerely, I went there because I had got ready to go; I left it for the same reason” (Journal). This comes close to “It seemed like a good idea at the time.”

From this point on Thoreau seems to have distanced himself somewhat from the Transcendentalists. He was outraged by the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which required free states to return escaped slaves to their owners in the South. He took an active part in the underground railroad smuggling slaves out of the South: on at least one occasion he provided shelter and a route to Canada for a fugitive slave. Thoreau continued to think, as his writings prove; but he was becoming more of an activist.

The most controversial episode of Thoreau’s life occurred in 1857, when he met John Brown of Kansas, an abolitionist who promoted armed insurrection on behalf of that cause, and gave him the fullest support, even writing and publishing ‘A Plea for John Brown’ after Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859.

Thoreau’s father died in 1859, which left Henry head of the family and responsible for his mother and sister. In 1860 he developed bronchitis and travelled to Minnesota for a cure. Here he met members of the Sioux Nation, and was concerned about their treatment by the federal government – an activist to the last. The cure did not work. Thoreau returned to Concord, made arrangements for the posthumous publication of The Maine Woods (1864), and died of tuberculosis on May 6th 1862.

Assessments

One tendency within Thoreau scholarship has been to divert attention from what he says by calling its context into question. He has been criticised for not being economically self-sufficient (when he did not set out to be); and Carl Bode has put forward a psychoanalytic explanation which sees Thoreau’s hostility to the state as linked to an Oedipal hatred of his father and John Brown as a father figure. Anything rather than acknowledge that Thoreau’s (admittedly threatening) ideas might be worth considering in their own right!

It seems more likely that what Thoreau saw in John Brown was a reflection of his own development. He had moved from being a thinker to being an activist. Emerson and his circle may have spoken and written against slavery, but they were not recorded as sheltering runaway slaves, as Thoreau did. Thoreau recognised in Brown someone who not only believed in a cause, but did something about it.

Thoreau can be presented as an outsider, but that does not appear to be how his Concord neighbours viewed him. Small communities can be intolerant of difference; but Thoreau was accepted as a member of his community. He was eccentric, perhaps: one of that increasingly rare breed, the Yankee individualist. Yet he got on with people; he gave freely of his time and thoughts to lecture in the Concord Lyceum (and was allowed to do so); and he kept getting hired. After all, he was a damn good surveyor, and knew how to make a good pencil.

© Martin Jenkins 2017

Martin Jenkins is a retired community worker and Quaker in London.