Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

War & Philosophy

Bergson: Rights, Instincts, Visions & War

Carl Strasen says Henri Bergson’s ideas about wars need rediscovering.

While he is almost forgotten today, the French thinker Henri Bergson (1859-1941) was perhaps the most famous philosopher of the WWI era. His extraordinary skills as a lecturer, and his 1907 bestseller Creative Evolution, made his visit to the US a media event and a public street nightmare. Strange as it seems to us now, the first rush hour traffic jam on New York’s Broadway was caused by the flood of people hoping to attend a Bergson lecture.

Bergson always approached philosophical problems by separating out quantitative differences – differences in degree or amount – from qualitative differences – differences in kind. Differentiating differences in kind from those in degree is a bit like the old saying in math classes that you can’t add apples to oranges. When this sorting and sifting of types of differences between ideas is done, Bergson hopes that the philosophic knot has been loosened enough to allow the circulation of understanding.

In his first two books Bergson uses this method to show how space is different in kind from time, and how the brain is different in kind from memory. The upshot of these seemingly arcane insights is a validation of human freedom against determinism, via what Bergson calls ‘ la durée’ (duration) which is the sort of extended consciousness we have when listening to music, for instance. In Creative Evolution, Bergson’s insights are extended into the flow of evolution, which is given a force of its own, called the élan vital, or vital impulse. This impulse finds manifestations in instinct and intelligence in all species. In his last work, The Two Sources of Morality and Religion (1932) Bergson finishes by pursuing how a closed society is different in kind from an open society. So Bergson’s effort to demonstrate and analyze differences in kind between the dualities of space/time, memory/brain, subjective/objective, intuition/rationality, lived time/measured time, human/insect, open society/closed society, trace the arc of his thought, with the prize being the reunion of religion and science. This effort in mending dualities made him Descartes’ heir, a Nobel Prize winner, and for some time in France he was philosophy’s superhero. Of Bergson and his kindred spirit philosopher William James, President Theodore Roosevelt noted that “every truly scientific and truly religious man will turn with relief to the ‘lofty’ thought of Bergson and James.” (Bergson and American Culture, Tom Quirk, 1990).

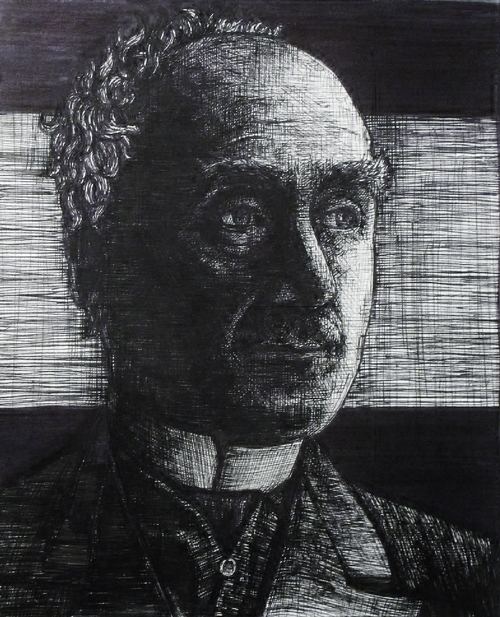

Bergson portrait © Woodrow Cowher 2018. Please visit woodrawspictures.com

War & Rights

The Two Sources of Morality and Religion was published in 1932 after twenty-five years of effort. In it, among other things, Bergson sought to understand the problem of war. Bergson was born in 1859, the year that Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was published. It seemed clear to Bergson that human societies had biological roots, and that the confluence of our technological development and our territorial instincts threatened our future as a species.

It is worth looking at WWI briefly to put our current problems with terrorism into perspective. Consider the Battle of the Somme in 1916. During the first day of combat, over 25,000 British soldiers were killed, with some regiments having 90% causality rates. The impact of WWI on European populations was profound: Germany lost 15.1% of its active male population; Austria-Hungary lost 17.1%; and France lost 10.5%. Yet unlike other philosophers of the era, such as Bertrand Russell, Bergson was a staunch advocate of continuing to fight WWI, because the Germans were trying to invade his homeland, France. He was only interested in peace after the Germans had been defeated.

The French government enlisted Bergson’s help in 1917 in a secret mission to America. As P.A.Y. Gunther writes in A Companion to Continental Philosophy (1994), he was “authorized to promise President Wilson that if he would bring the United States into the First World War on the side of the Allies, after the war Britain and France would back the creation of a League of Nations, dedicated to maintaining world peace.” And indeed, with Bergson adding to the tipping point, the US did enter WWI, and Germany was defeated. President Wilson then saw his dream come to life as the League of Nations began its work, and Bergson became the President of the League’s International Committee for Intellectual Cooperation. (Fittingly, the Committee provided the framework for a cooperative work between Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud entitled Why War?. Sadly, these two intellectual giants made little headway on their topic. Einstein hoped Freud had the solution, but Freud showed a flair for the obvious by saying that throughout history conflicts have been settled with violence.)

The League of Nations eventually failed, in the face of rising fascist aggression in the 1930s. Its successor, the UN, has at its foundation The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. According to Clinton Curle in Humanité (2007), the main author of the Declaration, John Humphrey, had Bergson’s The Two Sources of Morality and Religion as his inspiration. The Declaration is the archetypal human rights document, and by declaring that “recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world” it seeks to protect everyone with its list of rights.

Although Bergson was the strongest supporter of human rights, his vision was only partially implemented in the drafting of the Declaration. One problem is that human rights are often crushed just when they are needed most; when there’s a strong feeling of ‘us against them’ and cruelty against a minority becomes justified by the fears of the majority. This happens frequently in wartime.

The Human Instinct For War

Bergson argues that the ‘war-instinct’ is intrinsic to human, animal, and insect societies. Many animals also seem hardwired with what we would call cruelty. For example, if you supply wild birds with plentiful food in a bird feeder, they’ll frequently attempt to knock other birds off a perch instead of simply flying to a perch that’s open. Why? So that a rival gets less.

In ancient human times a small group with access to a stream or field and the right tools would flourish, and another group cut off from resources would perish. Bergson notes from this that “the origin of war is ownership, individual or collective, and since humanity is predestined to ownership by its structure, war is natural. So strong indeed, is the war-instinct that it is the first to appear when we scratch below the surface of civilization in search of nature. We all know how little boys love fighting. They get their heads punched. But they have the satisfaction of having punched the other fellow’s head.” (Two Sources, p.284.) He then observes that logic and rationality follow behind the pre-thought of instincts like a caboose follows the freight train, providing reasons for war after the war-instinct has already been stimulated into operating.

Bergson also describes here the constant interplay between closed and open societies. A closed society is instinct-driven and values security for its elite, and sometimes, to get what it wants it goes to war, since it can seize resources to protect its selected members. Thus closed societies are prone to starting wars: Bergson describes a closed society as one that endlessly circles the fixed point of war. An open society, on the other hand, is unbounded: it does not limit who its members are or what they must do. It seeks liberty, equality, and fraternity, not the protection of privilege.

Unfortunately, hoping that war can be eliminated by declaring the individual to be protected by their human rights misses the difference in kind between open and closed societies. Adding human rights into a closed society initially seems to work, but the two institutions won’t mix, like stirring water into oil. A closed society bases its security on defined roles and norms of behavior, so when a closed society views itself as under threat from ‘outside agitators’, it suspends human rights.

Closed societies aren’t a mistake as such; they form from the survival instinct, so it is pointless to belittle their supporters as ignorant. But they should know that left alone, closed societies gravitate toward war. The best one can hope for to prevent war is that the vision of a mystic with a message of love and peace will eventually permeate the closed society and move it toward being an open society, in a jolt. This jolt is the next step in Bergson’s theory of the development of society.

Of Ants & Men

Philosophical theories are especially interesting when they provide an ‘Eureka’ insight into unalike problems. Prior to writing Creative Evolution, on his vacations throughout France Bergson studied ants and bees. This must have seemed as an odd activity for a philosopher. But I know why he studied insects: to try to understand communal behaviour.

While hiking in the jungle of Ecuador, I saw leaf-cutter ants cross our hiking track. They made smooth trails transporting snipped sections of leaves relatively long distances. It looked a bit like an aerial view of a freeway, with red carrier ants hauling green leaf pieces at a steady rate, while unencumbered soldier ants overtook them. The ants bypassed plants as they made their way to a distant twenty-five foot clearing of light in the deep green gloom of the jungle. The light was due to the seeming devastation of a tree where the ants had crawled up the branches and systematically cut the leaves from all but one of them, where, curiously, a single intact leaf remained. “They always leave enough for the plant to recover,” our guide noted. I was skeptical, but found his observation mirrored in Bert Hölldobler and Edward Wilson’s extraordinary book The Ants (1990): “Another broad ecological interest is whether or not leaf-cutter ants husband their resources by directing their attacks so not to kill off too many plants close to home. Foragers have often been observed to shift their attentions from one tree to another without denuding any of them” (p.623). How is this possible? Do ants heed some current, jolt, or bolt of transmission that says “Enough! change!”?

In The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, Bergson suggests that exactly that sort of thing happens, but on a larger scale: fundamental changes in a human society’s behaviour come from the communication of an idea in a ‘jolt’. The jolt moves a closed society in the direction envisioned by mystics such as Christ, Moses, or Buddha, and is translated to the masses via education. As Bergson says in Two Sources:

“We represent religion, then, as the crystallization, brought about by the scientific process of cooling, of what mysticism had poured, white hot, into the soul of man…” (p.238) “…since [mystics] cannot communicate to the world at large the deepest elements of their spiritual condition, they transpose it superficially; they seek a translation of the dynamic into the static which society may accept and stabilize by education” (p.274).

The ‘frenzy’ of the mystic causes them to communicate a vision of a radically different direction to society, not based on selfish reasoning. Under its influence the closed society stops endlessly circling the fixed point of war; instead, it changes direction to become an open society, and save itself. However, the leap of the idea from the mystical visionary to everyone in society is sadly not inevitable. The struggle against injustice is slow and uncertain; and even the idea of waiting for mystical visions for social solutions is utopic at best and painfully naïve after the horrors of two World Wars and the Holocaust.

Bergson addressed this problem of the mystical vitalising of society thus:

“If mysticism is to transform humanity, it can do so only by passing on, from one man to another, slowly, a part of itself. The mystics are well aware of this. The great obstacle in their way is the same which prevented the creation of a divine humanity. Man has to earn his bread with the sweat of his brow; in other words, humanity is an animal species, and, as such, subject to the law which governs the animal world and condemns the living to batten upon the living. Since he has to contend for his food both with nature and with his own kind, he necessarily extends his energies procuring it; his intelligence is designed for the very object of supplying him with weapons and tools, with a view to the struggle and that toil. How then, in these conditions, could humanity turn heavenwards an attention which is essentially concentrated on earth? If possible at all, it can only be by using simultaneously or successively two very different methods. The first would consist presumably in intensifying the intellectual work to such an extent, in carrying intelligence so far beyond what nature intended, that the simple tool would give place to a vast system of machinery such as might set human activity at liberty, this liberation being, moreover, stabilized by a political and social organization which could ensure the application of the mechanism to its true object. A dangerous method, for mechanization, as it developed, might turn against mysticism: nay more, it is by an apparent reaction against the latter mechanization that it would reach its highest pitch of development… This [development] consisted, not in contemplating a general and immediate spreading of the mystic impetus, which was obviously impossible, but in imparting it, already weakened though it was, to a tiny handful of privileged souls which together would form a spiritual society; societies of this kind might multiply; each one, through such of its members as might be exceptionally gifted, would give birth to one or several others; thus the impetus would be preserved and continued until such a time as profound change on the material conditions impost on humanity by nature would permit, in spiritual matters of a radical transformation. Such is the method used by the great mystics.” (p.235.)

In the three large revolutions I’ve seen unfold in my lifetime, namely Nelson Mandela’s jolt to South Africa to change the regime of apartheid, Lech Walesa and Solidarity’s role in the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Ayatollah Khomeini’s overthrow of the Shah of Iran’s regime, the dynamic of ‘mystical frenzy’ acting upon a society has changed the behavior of its individuals in a deep way.

Conclusion

Despite the noblest and most rational thought of humanity, war is an intrinsic part of life. It is not a quirk, a rare exception, or a moral lapse of the ignorant manipulated masses. Bergson’s radical critique is worthy of study if we wish to stop endlessly circling the fixed point of war.

© Carl Strasen 2018

Carl Strasen remains a dedicated amateur student of philosophy after surviving twenty-five years in the salt mines of Silicon Valley, and analytic philosophy at UC Berkeley.