Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

Alistair MacFarlane considers the long and thoughtful life of Thomas Hobbes.

Thomas Hobbes was one of those very rare people who had a fundamental insight into what would come to dominate life centuries after their death. His insight was into human agency, the capacity to use information to control action. Hobbes had seen that groups of people working with shared information to a common purpose could generate shared agency. He thus conceived the amazing idea of artificial people. In Hobbes’ day this was a way of looking at large socioeconomic entities such as governments and their armies. Nowadays we can look at large globally distributed and coordinated transnational companies in the same way. These are now widespread, exercising a dominant effect on all our lives.

Hobbes called such a composite entity ‘Leviathan’, taking the name from a mythological sea monster. In what follows it will be used as a generic term for any form of large, coherent, purposive and organised group of people. In a stroke of artistic genius the original cover illustration for Hobbes’ famous book of that name showed a giant picture of the King towering over his realm, that on close inspection, turns out to be made up from lots of little people. Like real people, such Leviathans are born and die, prosper or struggle, collaborate or fight, and are driven by a variety of purposes, not all of which benefit the multitude of real people of whom they are composed. It is an idea at once commonplace yet of almost unimaginable significance for our future. Hobbes, a man whose life was dominated by fear of war and civil strife, had seen something truly fearsome.

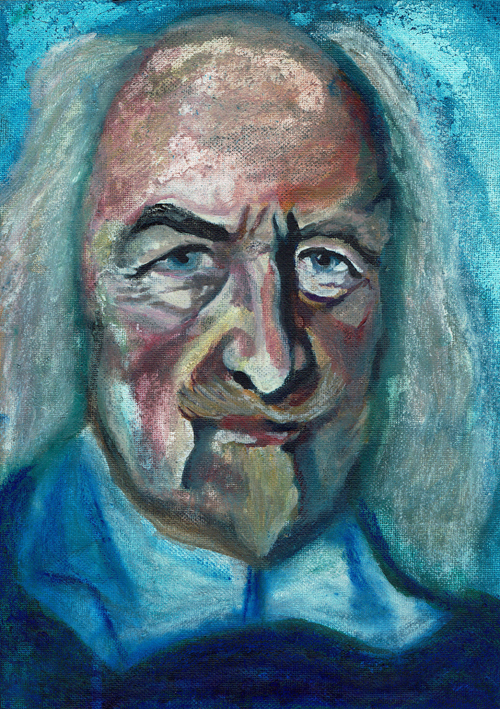

Thomas Hobbes by Gail Campbell 2018

Life

Thomas Hobbes was born on 15 April 1588 in Malmesbury, Wiltshire. He was plagued by fear throughout his life, and joked that his mother fell into labour on hearing that the Spanish Armada was on its way, “so that fear and I were born twins together.” His father, a poor clergyman, became an alcoholic and abandoned his three children to the care of his brother, who was a well-to-do glover. There is no record of the identity of his mother. Luckily, Thomas and his elder brother and younger sister were well cared-for.

It soon became clear that Thomas was an exceptionally gifted boy. He showed an outstanding ability in Latin and Greek, and proceeded to Oxford where, at Magdalen Hall (which later became Hertford College) over a period of five years he thoroughly mastered classical literature.

At the time aristocratic families were constantly on the lookout for promising tutors for their children, and in 1608 Hobbes was appointed tutor to the son of William Cavendish, first Earl of Devonshire. Hobbes later became his secretary, and maintained a close relationship with the Cavendish family for most of his life. As a member of their household he spent many years at Chatsworth, their country estate, or in London, meeting most of the leading politicians and literary figures of his day. In 1610, Hobbes toured France and Italy with his pupil (also called William), gaining a good insight into a life of intellect and scholarship. He returned to Chatsworth determined to become a major savant. During the next eighteen years he worked diligently in pursuit of this goal, but produced little except a translation of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, published in 1629.

When William Cavendish died in 1628, Hobbes accepted a position of tutor to the son of Sir Gervase Clinton, and remained with the family for the next three years, two of which were spent in continental Europe. Here Hobbes developed an interest in geometry and mathematics. This so reinvigorated his interest in philosophy that from this time on it dominated his life. In 1631 Hobbes returned to the Cavendish household as tutor to the new Earl and made his third visit abroad. On this visit he met Galileo in Florence and the circle of philosophers associated with Mersenne in Paris. He also met, and severely disagreed with, Descartes.

As the struggle between king and parliament began to spiral into the English Civil War (which occurred between 1642 and 1649), in 1640 Hobbes prepared a pamphlet, Elements of Law, to brief his aristocratic employers on the escalating conflict of interests. This was widely circulated among Royalists and greatly resented by Parliamentarians. Sensing the way the wind was blowing (against the aristocracy), fearful for his personal safety, and having accumulated sufficient savings for the purpose, Hobbes fled to France, where he spent the next eleven years. There he wrote and in 1642 published De Cive (On The Citizen), an exposition of his political philosophy.

Hobbes had gone to Paris because he saw it as a city of philosophers, but a growing lack of funds persuaded him in 1645 to accept a position as tutor to the exiled Prince of Wales, who had also fled there after his father’s execution. But Hobbes steadfastly continued his philosophy, and in 1651 published his masterpiece Leviathan. He presented a specially bound copy to his former pupil. It was to prove a shrewd investment. The Earl of Devonshire had made his peace with the new Cromwell government by paying a large lump sum for the return of land that had been confiscated as a penalty for supporting the former king.

Leviathan had given Hobbes a European-wide reputation, so after careful soundings among members of the new government who admired his work, he decided to take the risk of rejoining the Cavendish household in 1657. Although Hobbes had supported the king before the war, he had also denied the divine right of kings. By this argument, anyone in principle, and in particular the commoner Oliver Cromwell, could sit at the pinnacle of a Leviathan state.

Keeping an appropriately low political profile, Hobbes was able to enjoy a relatively untroubled life under Cromwell’s Protectorate. He resumed work on his system of philosophy, published De Corpore (On The Body) in 1655 and De Homine (On Man) in 1658. Hobbes’ remaining years were ones of incessant activity and of literary, mathematical and philosophical controversy. After the Restoration, Hobbes’ former pupil, now Charles II, invited him to Court and granted him a pension. From then on, Hobbes spent most of his time in London. He finally withdrew from worldly affairs in 1675 and retired to Chatsworth. Hobbes died in Hardwick Hall on December 4, 1679 at the age of 92, and was buried in St John the Baptist’s Church cemetery in Ault Hucknall in Derbyshire.

Frontispiece for Leviathan (1651)

Leviathan

The essence of Hobbes great insight into how society develops organisational structures lies in what in a modern context we would call ‘agency’. It is fascinating to look at his own words about this in Leviathan:

“For by Art is created that great Leviathan called a Common-Wealth or State, (in latine Civitas) which is but an Artifiiciall Man; though of greater stature and strength than the Naturall, for whose protection and defence it was intended; and in which the Soveraignty is an Artificiall Soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body; The Magistrates, and other Officers of Judicature and Execution artificiall Joynts [and] Counsellors are the Memory. Lastly, [are] the Pacts and Covenants, by which the parts of this Body Politique [are] set together.”

This famous passage is now of more historical than philosophical interest, and the anatomical detail pushes the metaphor past breaking point. But the crucial, breathtakingly simple, idea remains: Society develops by creating entities which function as super-persons, with a coherent, organised ability to set goals, reason out how to achieve them, put together huge coordinated resources, engage with each other, and exert a dominating influence over their constituent members. Most people, in modern advanced societies, lead a multiple existence. For part of their day they are components of a Leviathan, for the remainder they seek to be themselves.

Where did Hobbes get this idea that people in a developed society must necessarily lead a complex multiple form of existence which is more than a mere social contract between equals? One obvious possibility comes from acting in a theatre. An actor, when acting, is indeed an artificial person created by an author. Moreover any number of people can act the same part, so that the artificial person transcends the individuals who may play it. Similarily, groups of people create contracts to create super-groups – councils, governments, legislatures, companies… which in some sense, since they are created by us and composed of our like, must function as augmented versions of us.

In arguing why we must surrender part of our individual freedom to Leviathans, Hobbes compared that outcome with its alternative:

“In such condition [as before the formation of government], there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Leviathans are the price we pay for the advantages of civilisation.

Legacy

Hobbes is generally regarded as the founder of British moral and political philosophy, and as one of the greatest of English philosophers. For him, moral and political philosophy were of more than academic interest. They were of huge practical importance too, for he saw them as a means of counteracting the civil war that was the greatest of his fears. In his day, Hobbes was an admired all-round thinker. He made important contributions to optics, and to a materialistic explanation of human behaviour. His uncompromising endorsement of materialism aroused the hostility of religious authorities of all persuasions, who were enraged by his claim that if reason by itself is to be taken as a guide to action, then God is dispensable as a source of ethics. On his return to England after the Restoration, determined attempts were made to push a Bill through the House of Commons against atheism, and moves were made to investigate Leviathan. Hobbes accordingly burned any papers that might compromise him.

Two people I have covered in ‘Brief Lives’, Ada Lovelace (see PN 96) and Thomas Hobbes, have had startling visions of the future. Lovelace foresaw the possibilities which material agency would open up for computing, and Hobbes foresaw how human agents could combine to form superhuman agencies. As both these visions are increasingly integrated, with huge companies combining the use of information and manufacturing resources on a scale that challenges governments, the results will dominate our future. We face a fundamental dilemma: in seeking to make a better future, we must place our fate in the hands of people who share our fundamental flaws and limitations. And as Immanuel Kant said, out of the crooked timber of humanity nothing straight was ever made.

© Sir Alistair MacFarlane 2018

Sir Alistair MacFarlane is a former Vice-President of the Royal Society and a retired university Vice-Chancellor.