Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Friendship

Aristotle on Forming Friendships

Tim Madigan and Daria Gorlova explain Aristotle’s understanding of good friends and tell us why we need them.

Although he lived long ago, the ethical writings of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BCE) still have relevance to the present day, particularly when we want to understand the meaning of friendship. In Books VIII and IX of his work the Nichomachean Ethics (named in honor of both his father and son, who shared the name Nichomachus), Aristotle categorizes three different types of friendship: friendships of utility, friendships of pleasure, and friendships of the good (also known as virtuous friendships). Briefly, friendships of utility are where people are on cordial terms primarily because each person benefits from the other in some way: business partnerships, relationships among co-workers, and classmate connections are examples. Friendships of pleasure are those where individuals seek out each other’s company because of the joy it brings them. Passionate love affairs, people belonging to the same cultural or social organization, and fishing buddies all fall into this category. Most important of all are friendships of the good. These are friendships based upon mutual respect, admiration for each other’s virtues, and a strong desire to aid and assist the other person because one recognizes an essential goodness in them. (See Tim Madigan’s article ‘Aristotle’s Email, Or, Friendship in the Cyber Age’ in Philosophy Now 61 for further details on these categories.)

But, the questions remain – just why do we need friends? And if we do need them, how do such relationships arise?

Eudaimonia

Aristotle writes, “For without friends no one would choose to live, though he had all other goods” (NE, 1155a). But just why is this so? Because friends are central to Aristotle’s overall conception of what constitutes a good life.

In the larger context of the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle addresses what makes us human. In this book, as well as in other works, Aristotle asks the fundamental questions; What does it mean to be a human being?, and What goals will bring out our best? In this context, Books VIII and IX of the ten-book Nichomachean Ethics are part of his discussion of the nature of eudaimonia, a term often translated as ‘happiness’ but which literally means [having a] ‘good soul’. Friendship is part of what makes for eudaimonia, and connects to the nature of what it means to be human.

For Aristotle, the good life consists of developing one’s natural abilities through the use of reason, and a virtuous life is one where habits are formed that allow one to reach one’s full potential. Some goals, such as the desire for good health, wealth, or public recognition, can propel us to action; but such aims are not what Aristotle considered our ultimate goal or telos. Rather, they are all means to an end. The ultimate end or goal of life is eudaimonia, which is based upon self-fulfillment and self-sufficiency. “For the final and perfect good seems to be self-sufficiency,” Aristotle writes. “However, we define something as self-sufficient not by reference to the ‘self’ alone. We do not mean a man who lives his life in isolation, but a man who also lives with parents, children, a wife, and friends and fellow citizens generally, since man is by nature a social and political being” (1097a).

Philia

We are, as Aristotle points out, social and political beings. We cannot exist independently from everyone else. Our very development as humans is contingent on the proper, or natural, support given to us by other people. This leads us directly to the category of social relations Aristotle calls philia, which is the ‘friendship of the good’. For Aristotle, the best way of defining philia (what we might these days call ‘close friends’) is ‘those who hold what they have in common’. Essentially, philia is a personal bond you have with another being which is freely chosen because of the virtues you see in your friend.

If the only people we knew were our family members, our roles in life would be quite limited, as would be our opportunities for development. But remember Aristotle’s assertion that we are by nature social and political beings. Polis is the ancient Greek term for city, but it literally means ‘a body of citizens’, and it relates to the fact that most of us live not just within a family structure but rather within a larger political system. Yet most of the people in such a system are strangers to each other. If they were all related, it would be clearer what roles each person is to play (for instance, when a monarch has children, usually the firstborn is deemed to be the next in line to rule); but in most political systems there is more flexibility, and more opportunity for people to develop their talents in different ways. Good friends become useful in this sort of political situation.

Aristotle points out that if in fact all people in a given society were friends, there would be no need for laws, since we would naturally work out our differences: “When people are friends,” he writes, “they have no need of justice, but when they are just, they need friendship in addition” (1155a). Some utopian thinkers, such as the followers of the later Greek philosopher Epicurus, took this to mean that we should attempt to live only among friends. But Aristotle is quite clear that this is not possible, for the basic reason that friendship requires commitment of time and a trusting relationship, and there are natural limits to how many such connections we can make.

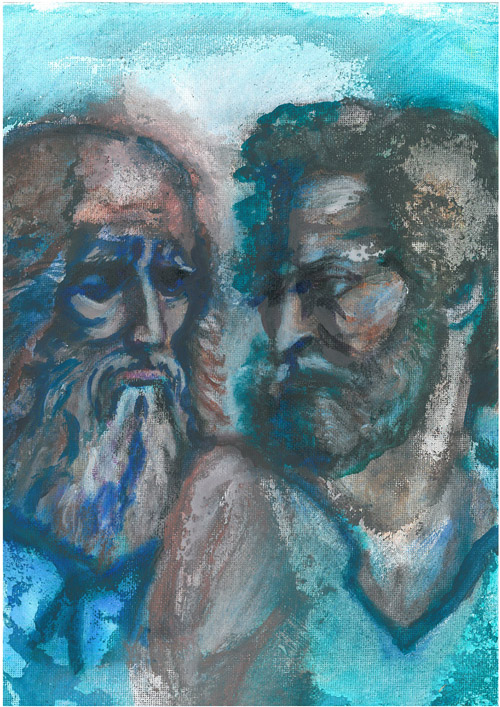

Aristotle & friend (Plato) by Gail Campbell 2018

Stanley Milgram & ‘Familiar Strangers’

An interesting example of this limitation is the so-called ‘familiar strangers’ experiment of the psychologist Stanley Milgram (1933-1984).

Milgram is best known for his rather infamous ‘Obedience to Authority’ experiments in the early 1960s, in which participants thought they were administering electric shocks to learners who didn’t give correct answers to multiple choice questions. The real purpose instead was to see how far these participants would go in administering pain (which unbeknownst to them was only being simulated by those getting ‘shocked’) merely because they were told to do so by an authority figure. But Milgram was a complex figure who came up with several other fascinating experiments. For instance, he and his students at the City University of New York tried to show how close two random people might be by determining the number of connections that they had with each other. This so-called ‘Small World’ experiment was the basis for the famous idea of ‘Six Degrees of Separation’, which claims that, at most, there are six links between people separating everybody from everybody else (this is also the basis of the game ‘Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon’, in which you try to show how any actor from any film is separated from a film starring Kevin Bacon by, at most, six other people). But where Milgram most relates to Aristotle is through his so-called ‘Familiar Strangers’ experiment. Milgram asked his students to perform a very simple experiment – so simple that at first many of them thought he was joking: go up to someone you’ve seen many times but have never spoken to, such as someone you see walking the halls of the school, or someone you see waiting every day for the same subway you take, and introduce yourself to that person, then report your experience. Simple enough. But, as Milgram’s biographer Thomas Blass points out, it turned out not to be simple at all – in fact, for many of the students it was emotionally overpowering. For once you’ve spoken to such a ‘familiar stranger’ you’ve formed a connection. They are no longer a stranger to you. You have each acknowledged each other’s existence. And the next time you see them you can’t just politely ignore them as you have in the past. You have to continue to make conversation, even if it’s just a banal “nice weather we’re having” comment.

Blass says that “Milgram felt that the tendency not to interact with familiar strangers was a form of adaptation to the stimulus overload one experienced in the urban environment. These individuals are depersonalized and treated as part of the scenery, rather than as people with whom to engage” (The Man Who Shocked the World, 2004, p.180). What made the experiment so uncomfortable is that it was a forced introduction, rather than a natural one. This nicely points out the fact that most of us, even while being ‘friendly’, are still shielding much about ourselves from others, even such basic information as our names, our family relations, where we work, and where we went to school. By sharing such information with others, we open up the possibility of their doing the same, at which point a relationship begins. That is also why it is easier to share such information, as well as much more personal information such as our political beliefs, our financial situations, and our sexual adventures, with strangers we’re likely to meet only once, say on a plane, train, or boat. Since we aren’t likely to ever see them again we’re more willing to be open, knowing that no relationship is going to form from the disclosure. (But, as Milgram showed in his ‘Small World’ experiment, it pays to be cautious – how can you be sure that stranger you’re talking to about how much you hate your boss or how you’re cheating on your spouse isn’t somehow connected, by just a degree or two of separation, from your boss or your spouse?)

“If You Want a Friend, Tame Me!”

For Aristotle, friendships, especially friendships of the good, don’t come easily, and must be cultivated. In such relationships, we reveal our innermost thoughts and aspirations to another. The trust between such friends is unlimited, and should not be given lightly. You have to get to know the other person, and that cannot be rushed. Your judgment should be a rational one, not one made in haste due to expediency or pleasure. “One cannot extend friendship to or be a friend of another person until each partner has impressed the other that he is worthy of affection,” Aristotle warns, “and until each has won the other’s confidence. Those who are quick to show the signs of friendship to one another are not really friends, though they wish to be; they are not true friends unless they are worthy of affection and know this to be so. The wish to be friends can come about quickly, but friendship cannot” (1156b). It takes time and effort.

One of the best examples of how such a friendship is formed can be found in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s 1943 classic children’s book The Little Prince. A visitor from another planet comes upon a fox whom he wishes to befriend. But the fox tells him that he must first be tamed. “What does tamed mean?” the Little Prince asks. “It is something that’s been too often neglected,” the fox replies. “It means ‘to create ties’.” When the little prince replies that he doesn’t have time, the fox poignantly replies: “The only things you learn are the things you tame… People haven’t time to learn anything. They buy things ready-made in stores. But since there are no stores where you can buy friends, people no longer have friends. If you want a friend, tame me!” As the fox understands, real friendship comes slowly, over time. If you tame me, the fox says, then I will be unique to you, and you will be unique to me. The little prince understands, and a beautiful friendship is formed.

Is Friendship Limited In Number?

Another important point at which Aristotle is in accord with Milgram is in regards to the view that we do not open up to all people because there are natural limits to the time and effort we can put into cultivating relationships. “To be friends with many people in the sense of perfect friendship is impossible,” he writes, “just as it is impossible to be in love with many people at the same time” (1158a). So Aristotle feels that there is definitely a natural limit to how many friends of the good one can have. If you have a handful of such relationships in your entire life, consider yourself fortunate. But what might the maximum number be? “Perhaps,” he writes, “it is the largest number with whom a man might be able to live together, for, as we noticed, living together is the surest indication of friendship; and it is quite obvious that is it impossible to live together with many people and divide oneself up among them. Furthermore, one’s friends should also be the friends of one another, if they are all going to spend their days in each other’s company; but it is an arduous task to have this be the case among a large number of people” (1171a).

Some modern thinkers are giving independent verification to these claims. The British psychologist Robin Dunbar’s research shows that the number is necessarily finite. According to Dunbar, “There is a limited amount of time and emotional capital we can distribute, so we only have five slots for the most intense type of relationship. People may say they have more than five, but you can be pretty sure they are not high-quality friendships” (Kate Murphy, ‘Do Your Friends Actually Like You?’, The New York Times, August 7, 2016). Five friends of the good is probably about all you can really sustain, he says.

To call friends of the good ‘perfect’, as Aristotle does, is not imply that there are no dangers involved in forming such relationships, or no possibilities that they might end. While they are the strongest type, they are not invulnerable. For instance, there is always the danger that one may lose a friend due to death, or to the friend’s moving away. This occurs in The Little Prince, when the prince says that it’s time for him to return to his home planet. “Ah!” the fox said. “I shall weep.” “It’s your own fault,” the little prince said. “I never wanted to do you any harm, but you insisted that I tame you…” But the fox replies that it has been worth it, “because of the color of the wheat”, which will always remind him of the little prince’s hair and the friendship they once had.

Happiness & Friendship

Let us end by returning to Aristotle’s views. He argues that in order to be happy, we need two things: good fortune and skill. We need to develop our talents into skills so that when good fortune arrives we will know how to make the most of it. But in order to develop our skills, we need the support of others, most particularly, of good friends. They will encourage us to make good use of our reasoning skills and to avoid vices – deficiencies or excesses of behavior – that lead us astray. Aristotle’s key to a good life is to achieve a ‘happy medium’ between extremes. And although there is no guarantee that good fortune will smile upon us, Aristotle felt that nature generally allows the possibility for human beings to develop their talents in ways that will allow them to be happy. And so, as the Beatles so memorably put it, we get by with a little help from our friends.

© Tim Madigan & Daria Gorlova 2018

Tim Madigan is Chair and Professor of Philosophy at St John Fisher College and President of the Bertrand Russell Society. Daria Gorlova is a graduate of St Petersburg State University and a member of the Bertrand Russell Society.