Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

L’Avenir (Things to Come)

Terri Murray takes in a subtle critique of academic philosophy’s anemic inertia.

Things To Come – L’Avenir (2016) – is French writer-director Mia Hansen-Løve’s tale of Nathalie Chazeaux (Isabel Huppert), a middle-aged philosophy teacher haunted by a vague malaise while seemingly having no insight into its cause. Things To Come manages to deliver a searing indictment of the state of Western philosophy in an exceptionally understated film. This fine balance earned Hansen-Løve the Silver Bear for Best Director at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival in 2016.

No Commitments

At the beginning of the film Professor Chazeaux walks through a picket line of demonstrating students to get into the Paris university where she works. When several students interrogate her apparent lack of concern, she retorts, “I’m not here to talk politics, but to teach.” In the classroom, one of her less-politicised students asks whether they can have a political debate – a request seemingly intended to steer their thought back to a relevant practical social application. But the professor’s indifference to political issues is so thorough that not only does she have no opinion on the strike’s objectives, she discourages her students from critically engaging in the matter. Instead she proceeds to read an obscure text by a little known philosopher, raising a completely abstract question for her students to ponder.

Soon afterwards, a former student of hers, Fabien, seeks Nathalie out to tell her how grateful he is for her inspirational mentoring, which has transformed his life. From having attended the famous École Normale Supérieure, which was her idea, he has dropped out of bourgeois consumer culture and moved to a farm, where he writes and lives a very spartan existence in keeping with his non-consumerist ideals. Nathalie has, by contrast, made no genuine commitments to anyone or any cause, and because of this she can hold on to nothing of her own. During one of her lessons, conducted in a park, she explains that philosophy is not about delivering truth, but about ‘the criteria for truth’. When she (somewhat unprofessionally) takes a call on her phone, realising that it is her needy mother, she abandons her students mid-lesson and rushes to her mum’s apartment. But no sooner is she with her mum than we see her resentment at taking the role of a dutiful daughter. As we see her life unfold, we discern that Nathalie is not truly reconciled to any decision she takes, nor to any relationship or role she plays. She lacks the courage of conviction. Yet when her husband announces that he’s leaving her for another woman, Nathalie doesn’t entertain the possibility of sacrificing her pride to try to keep him in her life, but instead puts the situation down to his lack of commitment, saying “I thought you would love me forever.” The idea that she might have to do something towards keeping him does not even occur to her. Instead she exacts her mild ‘revenge’ by excluding him from a family occasion; making him pay the price for having taken a decision, while accepting no responsibility for never taking any herself. We know from a comment her husband makes early on in the film that when they met she was handing out ‘commie’ tracts. She does not repent of her former activism, and admits to having been an activist for three years, but apparently that’s all in the past. Nathalie wants everything and everyone in her life ‘to a certain extent’, but nothing and no one so completely that she would genuinely risk sacrificing anything for it or them. Her elderly mother constantly makes demands on her time, and calls her at all hours with ploys for attention. After one too many of her mum’s feigned suicide attempts, Nathalie finally decides to move her to a care home; but then rationalises her decision by reminding her son that she chose an expensive one, which costs a small fortune and has a pleasant view.

Indecision plagues every facet of the professor’s life, including her relationships. She admires Fabien for his commitment to an alternative lifestyle, and wants to benefit from its positive aspects, but only by taking a temporary vacation into his exotic way of life, not by actually joining him to live at the rustic farmhouse, as he has invited her to do. Full commitment would entail dealing with the downsides of living outside of consumer culture, and she hasn’t the nerve for that.

Likewise, Nathalie is half-hearted in her role as a parent. Her son jealously claims that she prefers Fabien because he’s the son she’d have liked to have had, both physically and intellectually. This implies that she has not been totally engaged in her childrens’ lives either. Instead, it suggests that she has favoured her students, but even to them she remains only partially committed.

After a stint at Fabien’s farm, Nathalie declares, “To think, I’ve found my freedom. Total freedom. It’s extraordinary.” However, Nathalie is not free in her life but only from it. She has not made a life, but avoided making one. As such, she lives vicariously through others; first through Fabien, but implicitly through books and as a perpetual flaneur (sightseer) who samples from and enjoys temporary participation in other people’s commitments and life projects. In one scene she has travelled by train and car to reach Fabien’s farm, and she seems to appreciate the natural beauty of the uninhabited landscape. But we see in an extreme long shot that she has her nose stuck in a book. She is free in the sense of having no attachments, and therefore no responsibilities, because she has designed her life that way. The final shot in the film is grandmother Nathalie lovingly holding her daughter’s newborn baby, while her relationship to her own daughter is lukewarm at best.

Professor Chazeaux is a perpetual dilettante, selecting what she wants from life or from other people’s lives, but never sinking her energies or her passion into a definite plan or purpose of her own. As such, she is a proxy for what European/Western philosophy has become – an intellectual game, a pleasant pastime, but not a discipline with any real social application. She is but a pale imitation of the towering icons of post-war French philosophy such as Sartre, De Beauvoir, Camus or Merleau-Ponty, many of whom were active in the wartime Resistance or published political tracts, socially relevant plays or novels, and spoke in public about current events.

Professor Chazeaux conducts some research.

L’Avenir images © Les Films du Losange 2016

No Truth

In two separate scenes we gain insight into what philosophy is all about to Nathalie, and seemingly also to her husband, who teaches the subject to admiring university students. After a day of teaching, he comes home and tells Nathalie that he just spent his afternoon giving a lecture on rationalism and empiricism – the two competing philosophical theories of how to arrive at truth. They formed the central debate occupying Western philosophers from the late seventeenth century, until in the early-mid twentieth century, ideas about knowledge gradually morphed into extreme subjectivism, linguistic theories, conceptual schema, and finally, total skepticism about objective reality. These days, endless ink is spilled debating (or deflating) the correct criteria for truth, while virtually none has been devoted to taking a stand for a particular principle, policy, or model. Instead, academic careers rise or fall upon the relentless ritual deconstruction of other peoples’ ideas.

Many influences contributed to the development of this post-modern outlook: Nietzsche’s analysis of the relationship of language to reality, Lyotard’s focus on the role of narrative in human culture, Wittgenstein’s analysis of the linguistic structuring of human experience, Heidegger’s critique of metaphysics, Derrida’s deconstructionism – many influences converging to draw Western academia into a view of human knowledge that radically relativises claims to truth or knowledge.

The postmodern mind’s cynical detachment and spiritless dilettantism derives from this idea of how little knowledge can be claimed, and so how little basis for decision there is. From its self-relativising diffidence flows the nihilistic rejection of all values – a position that on its own terms cannot have any more epistemic clout than the meta-narratives it rejects.

Douglas Murray summarises this dismal state of affairs nicely in his book The Strange Death of Europe (2017) when he writes:

“Today German philosophy, like the philosophy of the rest of the continent, has been ravaged not just by doubt (as it should be) but by decades of deconstruction… Their deconstruction not only of ideas but of language has led to a concerted effort never to get beyond the tools of philosophy. Indeed, avoidance of the great issues sometimes seems to have become the sole business of philosophy.”

Professor Chazeaux exemplifies this postmodern mindset in which intellectual effort and academic commitment has transformed into a paradoxical certainty that no knowledge and no moral position can be held with any confidence. Yet through the tension it sets up between Nathalie and Fabien, L’Avenir brings to the fore the existentialists’ recognition that the grounding of the world for each of us lies in a subjective choice, not just in a subjective perspective. Indeed, by setting the non-committal academic in opposition to the committed philosopher who lives out his or her ideals, L’Avenir carries existential undercurrents of a distinctively Kierkegaardian tone.

No Certainty

Søren Kierkegaard’s existentialist vision of religious commitment is the polar opposite to the authoritarian submissiveness required by most religions. Religions often make subjectivity an offence to the established order. The individual who holds a God-relationship in opposition to the established orthodoxy is often accused of selfishness, ingratitude, or relativism. Kierkegaard on the contrary claimed that established Christianity evades the religious demand on the individual Christian by turning Christianity into “a construction of definitions” which depend entirely upon “these marks for recognizing piety directly by honour” (Training in Christianity, 1850, translated by Walter Lowrie, p.93).

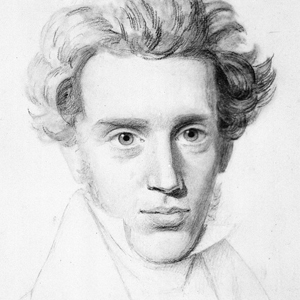

Søren Kierkegaard c.1840 by his father, Niels Christian Kierkegaard

For Kierkegaard, the fact that one’s view is only relative does not bring forth a morality of universal indifference and moral self-defeat. Kierkegaard thought it a mistake to assume that conviction in ethical life has to be an attitude of certainty based on knowledge. In Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846), he states unequivocally that Christianity is not a matter of knowledge. When the religious person operates in a mode of certainty, the individual becomes a philosopher who speculates over how to live, but not over his own life: he speculates about life in general, a sum of doctrinal propositions to which he ‘subscribes’ intellectually as a means of evading his own anxiety. For Kierkegaard, however, the individual’s confidence is not tantamount to certainty, but to “a paradoxical and humble courage.”

Therefore, in contrast to the usual religious demand to arrive at knowledge of what God wills, Kierkegaard substitutes the aphorism “innocence is ignorance”. When he writes in Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing that “to will the good is to will one thing”, his ‘one thing’ is not some particular good object or another, but rather good more generally conceived. That is to say, he is not concerned with the content of this or that moral principle or belief. His concept of ‘will’ neither claims, nor secretly believes in, its own superior knowledge. It renounces knowledge altogether, in exchange for a chosen ignorance. (And Kierkegaard’s understanding of the demands of religious faith is no less applicable in the secular sphere, where scientists and philosophers hunt for ultimate systems for knowledge devoid of subjectivity.)

No Essence

Both religion and atheism’s moral skepticism are currently in anxiety about the content of belief. To escape the impasse, we can perhaps turn to another existentialist philosopher; but one for whom existentialism is a humanism rather than a religious leap of faith.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s humanism shifts the moral focus from God to human beings. But like Kierkegaard, he deplored abstract, generalised accounts of ‘humanity’, which conflicted with his view that we are all free to make what we will of our lives, unbound by any predefined ‘human nature’. For example, the notion that ‘man is of intrinsic worth’ suggests that all human beings must be loved no matter what they may have done, simply because they are human. Sartre rejects this, beginning instead from the premise that there is nothing other than ‘the universe of human subjectivity’. Humans uniquely have the potential to invent themselves, but although moral values are constructed or created by individuals, we still have a responsibility to every other human being. To pretend that I act the way I do because of some external demand to which I must be accountable is ‘bad faith’. In refusing to acknowledge our freedom in such a way, we hope to escape the personal responsibility that is freedom’s logical corollary.

Some critics felt that this film should have had a car chase…

Like Kierkegaard, Sartre begins with the individual in his subjectivity, which for Sartre means his particular concrete existence in the world and history. And like Kierkegaard, Sartre begins with the radical freedom that arises from our realization that we cannot depend upon any universal or eternal ethical principles given to us either by religion or philosophy. Rather, we invent moral values through our chosen commitments and our actions. Yet Sartre’s claim is not that we must universalize the moral content of our choices, but that in choosing we at the same time acknowledge freedom itself as the ground of all values. I cannot consistently value my own freedom above the freedom of other people because to give my own freedom higher worth than theirs implies that I am intrinsically more valuable than them: “I am obliged to will the freedom of others at the same time as mine.” So for Sartre, when I choose, I am not only willing a particular action, I am also willing the freedom that allows me to make that choice. I am universalizing freedom as the foundation of my choices. In this Sartre seems to have bridged the gap between existentialist subjective individualism and the community ethics or moral responsibility of humanism.

In Sartre’s existential humanism, as in Kierkegaard’s existential religion, the central insight is that freedom or individual choice will overcome false confidence in universal truths or ideologies. In Kierkegaard’s view, “the only good is freedom”. He claimed that the difference between good and evil is “only for freedom and in freedom” and that this difference is never in the abstract but only in the concrete (The Concept of Anxiety, ed. and trans. Reidar Thompte, p.111, 1844.) And an individual’s consciousness of himself is the most concrete content of consciousness. “To understand a speech is one thing, and to understand what it refers to, namely, the personal, is something else; for a man to understand what he himself says is one thing, and to understand himself in what is said is something else” The Concept of Anxiety, p.142). Yet self-understanding in and through choice is one form of consciousness that postmodern academic philosophers seem to have forgotten. Hansen-Løve’s film perfectly captures the hollowness of their current endeavours.

© Terri Murray 2018

Terri Murray is the author of Feminist Film Studies: A Teacher’s Guide. She earned her BFA degree in Film & Television Studies from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, and has taught A-Level film studies for over 14 years.