Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

The Wisdom of Frugality by Emrys Westacott

Mark Waller finds out with Emrys Westacott that the simple life is not so simple after all.

A book about the pros and cons of frugal living might well be the sort of thing you’d come across in the self-help section at your local bookstore. The benefits of living simply, cutting out inessentials, using thrift and greater self-reliance to better manage our lives, stave off debt, quell the hunger for buying more and more stuff, live healthily and, while we’re at it, save the environment, are the regular ingredients of self-help books and videos. Down the ages, all sorts of mystics, gurus, sages and holy characters have also prescribed the frugal life. It’s long been the panacea for minds and bodies troubled by troubled times – and by and large, all times have seemed troubled to those experiencing them. In this book, Emrys Westacott, Professor of Philosophy at Alfred University, and occasional Philosophy Now contributor, cites plenty of examples of this aspect of the frugal message, but he locates his subject solidly in a philosophical tradition that goes back to ancient eras. There is some evidence Socrates linked virtue to happiness and happiness to simple living – as Epicurus (341-270 BCE) emphatically did a century later. Rightly or not, Socrates appears to us now as the quintessential philosopher – one who eschewed material riches in favour of the virtue-seeking life of the mind. It’s an enduring ideal. Some twenty-two hundred years after Socrates we find Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) living up a mountain “like a monk without a monastery”, as Westacott describes him.

In part Westacott is interested in seeing whether the ideas of the ancients – mainly the Epicureans and Stoics – have much traction today. He notes early on in his study that people tend to pay lip service to the ideals of frugality, “but you still don’t see many politicians trying to get elected on a platform of policies shaped by the principle that the good life is the simple life. On the contrary, politicians promise and governments strive to raise their society’s levels of production and consumption” (p.3). In a similar vein, people may well advocate or admire simple living and frugality while being reluctant to change their own lifestyles and levels of consumption.

Interior with an old woman combing a little girl’s hair by Jacobus Vrel 1654-1662

The questions Westacott raises to test the soundness of the supposed virtue of frugality and simple living make up the core chapters of this study. Why, he asks, have so many philosophers identified living well with living simply? Why is simple living so often associated with wisdom? Should extravagance and indulgence be viewed as moral failings? Or is frugality an outmoded value that most of us no longer think of as a moral virtue? Are there social arguments for or against simplicity quite apart from its consequences for the individual? The Wisdom of Frugality examines these seemingly straightforward questions in light of a long philosophical tradition and inspired by some of the concerns raised by the followers of Epicurus and the original Stoic, Zeno of Citium (334-262 BCE).

Westacott’s discussion of why simple living is supposed to improve us untangles some of the standoffs between competing conventional wisdoms, and shows why what we think of as fairly solid moral ground is almost always treacherous. This could be because nuanced appreciations of simple living tend to get cast aside or boiled down to either/or simplifications. Indeed, the book’s subtitle, Why less is more – more or less, is not a fence-sitting rider to the main title, but a warning that the subject is far from straightforward. The Wisdom of Frugality discusses how generalizing oversimplifies some of the ideas and ideals of frugality that have come down to us from the sages of old. For example, arguments in favour of simple living usually support the view that it is morally desirable because it is indicative of sound character, superior values, and integrity, in contrast to the shallowness and superficiality of materialistically driven hedonism. But on the contrary, frugality “can sometimes foster (or bespeak) miserliness; poverty can breed unsavory traits and provoke desperate, even criminal remedies; some important values, like truth or scientific progress may require significant expenditure for their realization; and while excessive indulgence in luxury may constitute what some would criticize as a ‘shallower’ form of existence, the precise meaning of and justification for this claim is hard to spell out” (p.71).

In this sort of way the too-easy premises of many proponents of frugality fail to withstand Westacott’s interrogations. He repeatedly shows how a particular line of argument only works up to a point, and can be thrown off balance by counter-examples; but that these too won’t lead you to definitive answers. Westacott claims that we find frugality attractive because our attitudes today are ambivalent: we accept acquisitiveness as a necessary condition of economic growth and prosperity while “denouncing it as an undesirable character trait that bespeaks false values and unethical conduct” (p.162). But, economics aside, extravagance can do us a lot of good, Westacott argues, broadening our range of experiences. And extravagance fuels culture. Without the extravagance of the privileged few in the past, we wouldn’t have such a rich cultural heritage to enjoy. Frugality, conversely, risks breeding parsimoniousness, restricting our ability to enjoy much of what the world has to offer. Wealth gives us security and leisure, and attaining it denotes individual achievement. Material progress has resulted in more people living longer, accessing education and health and benefitting from science and technology. The frugal sages of old lived in far simpler societies, and the world has since changed. All of which prompts Westacott to ask whether their wisdom isn’t simply outdated. Frugality as a lifestyle choice may be well and good for a scattered few who decide to go off grid in a nostalgic reach for the simpler ways of a largely imaginary past, but it is unfair and probably unrealistic to expect the majority of people to follow suit.

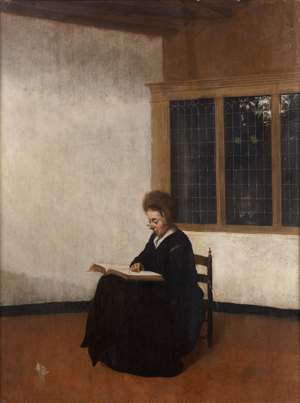

Une femme á sa lecture by Jacobus Vrel 1654-1662

Despite such carefully examined reservations, Westacott looks at how the lessons of frugality could be applied to how we run our societies, to make them better planned, more rational, fairer, happier, and far less wasteful in terms of human and natural resources.

The environmental arguments for simpler living and frugality are perhaps the most pressing in global terms, as most of the problems of the environment, from climate change to the destruction of ecosystems, have to do with how we (mis)use what’s available to us. Westacott’s general argument here is that if more people shifted their lifestyle in the direction of frugal simplicity in the way the sages of old proposed, this would reduce our collective negative impact on the environment. This frugal wisdom of the past still has much to offer us, then.

The book could have examined in greater detail the implications of the fact that around the world people live in very different contexts. Applying ideas of simpler living to societies where poverty and inequality are not only pervasive but deepening is an especially hard sell. The view that despite some reversals, the course of human history is nevertheless on the up and up, because overall improvements in the quality of life have increased among greater numbers of people, needs to take better account of negative trends. The picture is decidedly mixed. For instance, in South Africa, where I live, more people now have access to technology than ever before, the education and the health system now serves the majority of people better than during white minority rule, and middle class lifestyles are available to more people. But poverty and extreme economic inequality are increasing in this country. Social dysfunction and violence are more widespread and intense, and the massive migrations from deeply impoverished rural areas to the peripheries of urban hubs are further deepening these trends, and generating new problems. In these respects South Africa is like much of the rest of the developing world. Too many people are forced to live brutishly simple lives.

None of which detracts from the example of the frugal sages, or of the excellent application of philosophical enquiry Westacott brings to this refreshingly multidisciplinary study. It is perhaps because we have ignored the lessons of simplicity and frugality so comprehensively that the problems we now face as societies seem insurmountable without drastic upheaval and change.

We can’t say we weren’t warned. The Roman Epicurean poet Lucretius, who lived in the first century BCE, would probably see our plight as a familiar one: “Skins yesterday, purple and gold today – such are the baubles that embitter human life with resentment and waste it with war.”

© Mark Waller 2018

Mark Waller is a freelance writer and translator living in Pretoria, South Africa.

• The Wisdom of Frugality: Why Less Is More – More or Less, by Emrys Westacott, Princeton UP, 2016, 328 pages, $15.99 pb, ISBN: 0691155089