Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Santa Claus: The Movie

Chris Vaughan says “Bah humbug” to consumer society.

Santa Claus: The Movie (1985) is without doubt, and intentionally or not, a bold statement about how capitalism hijacked Christmas. It did so at some point during the Twentieth Century and in much the same way that early Christians absorbed the Roman festival of dies natalis solis invicti (‘The Birthday of the Invincible Sun’) on 25th December into their own ideas of divine birth in order to appease the party-going Roman public.

Had Eric Fromm (German sociologist and philosopher, 1900-1980) lived just five more years, no doubt he would have seen this movie and shouted, “I know where they are coming fromm!” For Santa Claus: The Movie essentially embodies the central arguments of his 1955 book The Sane Society. Like other Frankfurt School philosophers such as Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse, Fromm’s main concern was the alienation of humanity through the rise of consumerism. He expands on Marx’s description of a steadily growing dissociation of the worker from their work in industrial society, presenting a detailed story of how consumer culture causes widespread human alienation from life. He blames the totally profit-centred goals of big business in the 1950s. Add to this the arguments of Marcuse’s One-Dimensional Man (1964) and Adorno’s essays collected in The Culture Industry (1991) and The Stars Down to Earth (2001), and the reasons behind the unstoppable spread of a consumer-orientated world in which ‘economic man’ is the dominant species, become devastatingly clear. The difference between the Twentieth Century’s ‘Super Capitalism’, as Fromm calls it, and the normal capitalism of the Seventeenth-to-Nineteenth Centuries, is that in the Twentieth Century West the market became the human raison d’être. Previously money had been a means to satisfy human ends; now it had become its own end, and the employee no more than an appendage to the economy. In Super Capitalism, people exist to serve abstract market forces. Fromm puts it neatly, saying that the faith society once put in God, it now invests in the market.

Grotto or toystore?

Film images © Tristar Pictures 1985

Modernisation of the Means of Christmas Toy Production

So, what does the less-than-festive Frankfurt School have to do with Santa Claus: The Movie? The School’s arguments are repeatedly illustrated by aspects of the movie. It’s not much of a stretch to say John Lithgow’s character B.Z. is the absolute personification of Fromm’s dehumanising Super Capitalist. Cigar munching, evil-cackling B.Z. puts profit before all other concerns. In B.Z.’s set up, both worker and consumer are merely one-dimensional tools, abstractions in the bigger acquisitive picture. Not only is he less concerned with the quality of his products than his sales figures, he is even willing to put potentially lethal toys on the market – provided he has a fall guy.

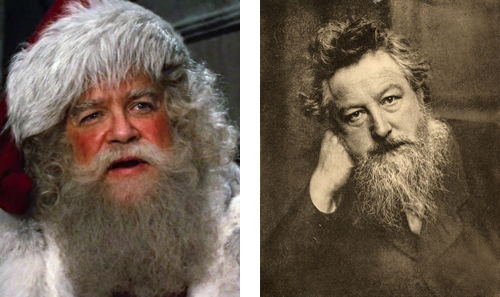

His patsy takes the form of the unwitting elf Patch (Dudley Moore). Patch enters B.Z.’s scene already a convert to industrialisation. He has come to New York from the William Morris-esque Arts & Crafts-type workshop community of Santa’s Grotto. Santa is played by John Huddlestone – note his uncanny resemblance to a certain bearded Victorian radical. Patch had tried to introduce Fordism into the Grotto – that is, the automated mass production of toys rather than their craft production – with predictably shoddy results. Patch’s products literally fell apart, leaving kids with that familiar sinking feeling that there’s nothing in life of any real quality that’s free or magically comes down chimneys. But as Patch himself says when his complex machine starts wheeling and conveying toys at incredible speed: “This is the Twentieth Century!” Indeed, before Twentieth Century Super Capitalism, the competition ushered into the Grotto by Santa pitting Patch against the traditionalist Puffy for the position of chief helper didn’t exist in the same way. The precise questions of hierarchy and position, promotion and career progression that their competition explores, are tied to the Grotto’s potential place in the Twentieth Century that belongs to B.Z. and the Super Capitalists. Santa is short-sighted when he chooses Patch over Puffy based on the quantity of toys produced.

By and large Santa remains medieval. From the hourglass indicating the passing centuries at the beginning of the film, it seems that Santa starts out in the Fourteenth Century and feels no need to update his manufacturing methods or infrastructure for six hundred years. In fact, the only change before Patch’s effort at industrialisation has been the addition of a merit system at the behest of Mrs Claus, which awards good children and punishes naughty children. This kicked in roughly around the Nineteenth Century because of a brat who liked torturing cats.

William Morris; Santa Claus

A Christmas Advert

Leaving aside the anachronism of the Grotto, back in the big city we’re introduced to a homeless kid, Joe. Street-smart Joe has literally been left out in the cold; but he’s taken under Santa’s wing, and later befriended by B.Z.’s young niece Cynthia.

In a pivotal scene, Joe peers through a window of a McDonald’s at middle-class families munching Big Macs. This evokes the traditional orphan peering-through-window-in-the-snow-at-warm-festive-household scene; only here it is McDonald’s which frames the ideal Christmas desire. Joe does not yearn for the warmth of belonging to a family in festive spirits; it’s through brand affiliation that he can (momentarily) escape the bitter cold. Bringing Joe in to a safe and warm environment is only a matter of his acquiring the right appetites and desires. And when Cynthia leaves a plate of food and a can of Coca Cola outside for Joe, there’s nothing ambiguous about the label – as an emblem of Christmas, it infers warmth. (McDonald’s and Coca Cola both had promotional tie-ins with the movie.)

The idea of a lack of any liveable life outside this system is reinforced by using New York to represent late Twentieth Century society. Outside of New York (or consumer Super Capitalist society), all we see are wastes of snow or depopulated mountain regions; or frozen Lapland itself, where Santa, Joe, Cynthia, and Patch eventually retreat from the devouring self-centred city.

Our last view of B.Z. is of him hurtling into space, elevated by his latest product, candy that can make you fly. If we take the Twenty-First Century Christmas industry as any indicator, it’s safe to say B.Z. eventually returned down to Earth and went on to conquer Christmas. Santa may have saved Patch, Joe, and Cynthia by retreating with them into the pre-industrial William Morris hinterland of medieval Lapland. But the real sequel to this unsung socialist classic is B.Z.’s fantasy of ‘Christmas II’ come true: Black Friday.

© Chris Vaughan 2018

Chris Vaughan is a writer currently living and working in Gibraltar. His fiction can be found at Ambit, The Lifted Brow and some other places. He writes reviews for The Rumpus, and has seen Santa Claus: The Movie at least twenty times.