Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Can an ‘Ought’ be Derived from an ‘Is’?

Philippa Foot says it’s super easy, barely an inconvenience.

One thing about running a philosophy magazine, with the resulting creative chaos, is that occasionally when tidying up you stumble across memos from your philosophical heros. At least, that was my experience recently.

One of my greatest philosophical heros was the Oxford philosopher Philippa Foot (1920-2010). One of the world’s best known and most original moral philosophers, she reignited interest in virtue ethics. She also invented the ‘Trolley Problem’– an ethics thought experiment that recently inspired an entire episode of The Good Place! At university my ethics tutor Anthony Price introduced me to another of Foot’s groundbreaking contributions, a 1972 paper called ‘Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives’. It relates to a critical problem at the very root of ethics: the ‘Is-Ought Problem’ first pointed out by David Hume in the 18th century. Hume noted that all systems of ethics about which he had read seemed to progress from ordinary statements about what is the case to claims about what ought to be the case, and that it wasn’t clear how they did this, as statements of the latter kind are completely different from the former. It is a principle in logic that nothing can appear in the conclusions of a valid argument unless it also appears in the premises.

Philippa Foot portrait © Clinton Inman 2018. Facebook him at clinton.inman

A huge debate reignited in the 1960s and 70s over whether an ‘ought’ could be derived from an ‘is’, or to put it another way, whether propositions about what ought to be done can be logically derived from propositions that are purely statements of fact. Some have argued that if this is in principle impossible, then there can be no way to derive any system of ethics from facts about the world, and that anyone who claims to do so must be mistaken. All ethical systems would be subjective, and none of them could ever be proven true. Debate over whether this ‘is-ought gap’ could be crossed raged in the journals, with ingenious papers by the likes of Richard Hare, John Searle and Max Black. Foot seemed to elegantly sidestep the problem with her famous paper. Immanuel Kant had said that ethics is the realm of categorical imperatives (“One should never lie” and so on), but Foot suggested that our moral lives could instead be based on hypothetical imperatives. These are “If… then” statements. For example, “ If you want some sugar then you should walk to the shop before it closes.” So if you do in fact want some sugar, you should walk to the shop. Otherwise not. It’s easy to invent examples in ethics: “If you want the happiness and safety of those you love, then…” and so on. Hypothetical imperatives can be proven true or false. They don’t require any crossing of the ‘is-ought’ gap, and Foot claimed that they could form the basis of our moral lives including voluntarily banding together with like-minded people to promote the common good. I found her argument plausible and actually rather inspiring.

In 2001 I finally had the chance to interview Philippa Foot for Philosophy Now. She poured me tea in her Oxford home and we chatted about her then-new book, Natural Goodness. I asked her about how her new work related to her paper on hypothetical imperatives, and she told me that she believed she had been wrong about that, and had completely dropped the idea. I wanted to ask her more about that, but she mostly preferred to talk about her new work, and so we did. After a delay the interview finally appeared in Philosophy Now Issue 41. I always regretted not pressing Foot a little more about the question of ‘is’ and ‘ought’, and especially regretted that after her death in 2010.

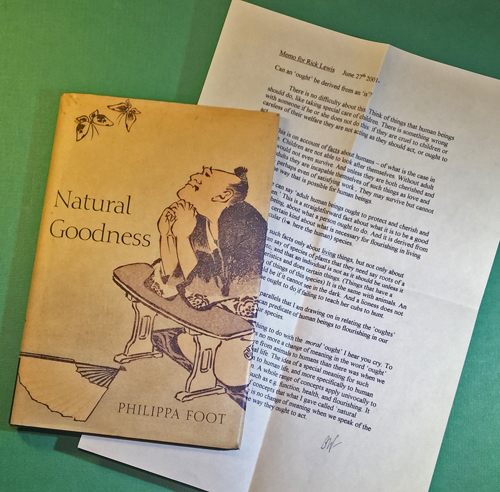

Then recently I noticed that my copy of her book on Natural Goodness seemed to be in two separate places on the bookshelves simultaneously. I toyed with various metaphysical explanations before realising that I had two copies of the same edition. I opened the more obscurely located copy, and a folded piece of paper fell out. It seems that Philippa Foot wrote it as a follow-up after our meeting. I think she must have mailed the note to me folded and tucked inside a copy of her new book. I assumed the book was a review copy, and as I already owned a copy I didn’t bother opening the new one. I just put it on the shelf.

What she wrote in it won’t startle Foot scholars as it is certainly very much in tune with what she was arguing in Natural Goodness. But it was nice of her to specifically address my interest in the Is/Ought problem and I thought I’d share her memo with you.

Does it demonstrate, as she thought, that you can derive an ‘ought’ from simple facts about humans? I’m not sure. I’ll leave it for you to decide.

Rick Lewis

Memo for Rick Lewis, June 27th 2001

Can an ‘ought’ be derived from an ‘is’?

There is no difficulty about this. Think of things that human beings should do, like taking special care of children. There is something wrong with someone if he or she does not do this: if they are cruel to children or careless of their welfare they are not acting as they should act, or ought to act.

This is on account of facts about humans – of what is the case in human life. Children are not able to look after themselves. Without adult care they would not even survive. And unless they are both cherished and taught by adults they are incapable themselves of such things as love and friendship – perhaps even of satisfying work. They may survive but cannot flourish in the way that is possible for human beings.

So we can say ‘adult human beings ought to protect and cherish and instruct children.’ This is a straightforward fact about what it is to be a good or bad human being, about what a person ought to do. And it is derived from other facts of a certain kind about what is necessary for flourishing in living things in a particular (i.e. here the human) species.

There are such facts only about living things, but not only about humans. For we can say of species of plants that they need say roots of a certain kind, etc, etc, and that an individual is not as it should be unless it has certain characteristics and does certain things. (Things that have a function in the lives of things of this species) It is the same with animals. An owl is not as it should be if it cannot see in the dark. And a lioness does not do something that she ought to do, if failing to teach her cubs to hunt.

These are parallels that I am drawing on in relating the ‘oughts’ and ‘shoulds’ that we can predicate of human beings to flourishing in our case – in the case of our species.

‘But this has nothing to do with the moral ought’ I hear you cry. To which I reply that there is no more a change of meaning in the word ‘ought’ or ‘should’ when we move from animals to humans than there was when we moved from plant to animal life. The idea of a special meaning for such words when we apply them to human life, and more specifically to human action is a complete illusion. A whole range of concepts apply univocally to all living things – concepts such as e.g. function, health, and flourishing. It is within this logical space of concepts that what I have called ‘natural goodness’ belongs, and there is no change of meaning when we speak of the way humans should be and the way they ought to act.

P.R.F.

© Prof. Philippa Foot 2001