Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Street Philosopher

Hounded in Holland

Seán Moran considers canine companions.

Photo © Seán Moran 2019

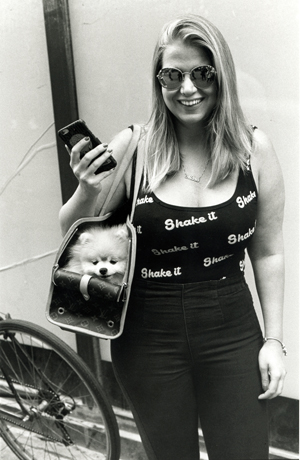

Dogs are good for us: (wo)man’s best friend has measurable effects on our wellbeing. When we gaze lovingly into the eyes of our faithful pet, our brains secrete the feel-good hormone oxytocin, usually associated with maternal closeness and mate-bonding. And canine company can reduce both our blood pressure and the stress hormone cortisol. But are we good for dogs? It looks that way: a recent Japanese study shows that when they’re with us, dog brains secrete oxytocin too. The dog in my photograph, taken in the Netherlands, seems to be a happy pampered baby-substitute. It also fits with empirical research showing behavioural and neuroendocrine similarities between dog ownership and mother-and-infant relationships.

However, some people mistreat dogs, and pedigree breeding has also produced various health issues alongside the human-aesthetically-pleasing outcomes. Pugs and bulldogs may look cute (to some), but around half of them have breathing problems. Their flat-faced appearance is attractive (to some), mimicking aspects of human baby morphology and triggering bonding responses; but at the expense of their efficient breathing. There is also an argument that even keeping a healthy dog, and treating it well, is morally reprehensible. The clue is in the word ‘keeping’. A kept dog is not a free animal, able to roam without restriction, to copulate, urinate, and do spontaneously all the things its doggy heart desires. It relies on our permission for everything, and has lost its wild autonomy. The animal has been domesticated and neutered (perhaps literally), becoming a pale shadow of its wolf ancestors. It suffers from a type of Stockholm syndrome: loving its captor and having no desire to escape.

Along these lines, the environmental ethicist Stuart Spencer suggests that since dogs are pack animals, keeping one in isolation denies its telos. His use of the Greek word is interesting. It’s a key concept in Aristotle’s philosophy. It means ‘end’, ‘purpose’ or ‘goal’. For instance, a knife’s telos is to cut. So, in an Aristotelian way, dogs have a built-in purpose, and to interfere with this is to subvert nature’s plan and hence be unethical. Spencer goes on to say that, “Other actions more deliberately infringe telos and autonomy. Enforced shampooing… hair-cutting of poodles; putting animals in clothes” (Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 2006).

I’m not entirely convinced by this teleological argument. I, for one, have used a table knife in lieu of a tyre-lever when fixing a bicycle puncture. That isn’t the knife’s telos, but it still did an adequate job (though it didn’t go down too well at home). And I’m sure that I’d rather be shampooed, coiffed and clothed than take my chances in the wild against Tennyson’s ‘nature, red in tooth and claw’. Being carried around in a basket by a Dutch Post-Millennial might become tedious after a while, though. (That’s a sentence I never expected to write).

Some would say that here I’m guilty of anthropomorphism: of projecting human sensibilities onto a non-human creature. But I am an anthropos (Greek for ‘man’), so can only conceptualise the world from an anthropocentric perspective. And just as humans can’t imagine what it’s like to be a bat (as Thomas Nagel convincingly argued), so neither can we fully put ourselves into a dog’s furry shoes. Canines inhabit a world of smells and sounds we can’t even conjure up. Furthermore, the dog is just as guilty of perspectival bias. It indulges in ‘canomorphism’ by seeing its owner as the leader of its pack.

Arguments based on the notion of a fixed telos often involve essentialism, with all its problems. In Essentially Speaking (2013), Diana Fuss defines essentialism as “a belief in the real, true essence of things, the invariable and fixed properties which define the ‘whatness’ of a given entity.” So a naïve (and sexist) essentialist might regard, say, a woman as being submissive to her man and nurturing to her children. Such hardening of categories puts artificial constraints on what’s acceptable, and limits human flourishing. It’s one thing to notice typical feminine attributes and aggregate these into an informal norm; but quite another to deny the womanhood of individual women who inhabit the outer reaches of the female bell-curve. So who are we to deny the doggiehood of even the most pampered pet? Canis lupus familiaris can also occupy a wide distribution of lifestyles and still be regarded as proper pooches. And the details are up for negotiation. To take Spencer’s example, if Fifi really objected to being shampooed, a sensitive owner would notice this and limit its frequency.

There is something symbiotic in these unspoken negotiations that tames the behaviour of both parties. We have domesticated dogs over millennia, but they have civilised us too. Around fifteen thousand years ago we simultaneously started to build agricultural settlements and see that animals from other species were worthy of our love. We are probably not barking up the wrong tree in speculating that human friendships with Canis lupus had a beneficial impact on the interactions between members of Homo sapiens in these early settlements. We became more empathetic.

Dog-Philosophers of Ancient Greece

Plato goes further than this, and actually credits dogs with being philosophers. In the Republic he says that:

“A dog, whenever he sees a stranger, is angry; when an acquaintance, he welcomes him… Your dog is a true philosopher… Why, because he distinguishes the face of a friend and of an enemy only by the criterion of knowing and not knowing. And must not an animal be a lover of learning who determines what he likes and dislikes by the test of knowledge and ignorance?… And is not the love of learning the love of wisdom, which is philosophy?”

If one Greek philosopher regarded dogs as philosophers, a group of Greek philosophers, the Cynics, saw themselves as akin to dogs. Their name acknowledges this: the word ‘Cynic’ comes from the Greek kunikos, which means ‘dog-like’.

In many respects, the Cynics were barking mad, but two of their traits were quite attractive: 1. Living a ‘natural’ life, with no respect for convention; and 2. Speaking truth to power (parrhesia). According to the biographer Laertius, Alexander the Great came upon the founder of the Cynics, Diogenes of Sinope, while Diogenes was sunbathing at the Craneum gymnasium. Alexander announced his high status to Diogenes by saying, “I am Alexander the Great King.” Diogenes replied with his own rank: “I am Diogenes the Cynic” (which is to say, Diogenes the Dog). Alexander stood over him and said, “Ask of me any boon you like”; to which Diogenes answered, “Get out of my sunlight.”

Plato described Diogenes as “Socrates gone mad.” In return, when Plato endorsed Socrates’ definition of a human being as a ‘featherless biped’, Diogenes took a plucked chicken into Plato’s Academy and announced, “Here is Plato’s man.” Plato was forced to modify Socrates’ definition of ‘human being’ to ‘broad-nailed featherless biped’.

Amusing as he was, Diogenes would almost certainly be no-platformed in many present-day academies. He held essentialist views about gender, as Laertius recounts: “Seeing a young man behaving effeminately, ‘Are you not ashamed,’ he said ‘…for nature made you a man, but you are forcing yourself to play the woman?’”

Bad Fido, Good Fido

Let’s return to my photograph of a broad-nailed featherless biped with her manicured furry quadruped on the streets of Amsterdam. Are we to say that this dog is essentially a wolf in a basket who has been shamefully robbed of nature’s intentions? Or might the dog now identify as a princess, to be mollycoddled and live the sort of luxurious life Diogenes would reject? It seems, though, that only human beings can redefine ourselves in this latter fashion, that is, culturally rather than being defined by nature. Moreover, according to Jean-Paul Sartre, we (humans) must embrace our radical freedom and so constantly redefine ourselves in an authentic way. To do otherwise is to show ‘bad faith’ (‘mauvaise foi’) – like the café waiter Sartre describes in Being & Nothingness (1943), whose precise and mannered movements show that he has discarded his real nature and allowed his role to define him. But for Sartre, his ‘real nature’ has not been predetermined: it is up to the waiter – as a free human being – to define it for himself, and to keep on defining it. Sartre is no essentialist.

We may wonder to what extent the young woman in my photo is defined by her role as a Post-Millennial Amsterdammer. Her generation – Generation Z – has been labelled hyperconnected, open-minded, and compassionate; but also risk-averse, snowflaky, and afflicted with short attention spans. Yet like any essentialist analysis, this is a sweeping generalisation. If it applies at all, it applies only ‘for the most part’ as a handy informal norm. So I should not have been surprised recently when lunching with another strong, independent Post-Millennial woman at a smart pavement café in sight of the Eiffel Tower in Paris (you see the sacrifices I have to make as your Street Philosopher). She produced a fountain pen to write in her notebook, kept her (non-smart) phone in her bag, and talked about her vinyl record collection. Her brave travel plans and lengthy PhD research undermined any labelling as ‘risk averse’ or ‘of limited attention span’. I was so entranced that I didn’t notice whether or not our waiter showed any mauvaise foi.

The flaunted smartphone and canine companion of the Dutch Gen Z woman in my photograph advertise her stereotypical connectedness and compassion. As far as I could see, they were both making her happy, and approachable. The smartphone unites her to the elevated cyberworld, and the dog anchors her to the earthy, animal realm. Overall, their relationship seems benign. Each party in that canine-human dyad helps the other to flourish. Granted, the dog has to suppress its inner wolf; but the Post-Millennial human has to make some concessions too: her freedom is limited by having a dog to look after. Both have made compromises, and by doing so each has enriched the life of the other.

© Dr Seán Moran 2019

Seán Moran teaches postgraduate students in Ireland (which remains a member of the European Union). He is also Professor of Philosophy at a university in the Punjab.