Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Question Marx

How Can Anybody Change Culture?

Kevin Brinkmann tells us, with the help of Althusser, Gramsci and Mannheim.

These days it seems almost everybody is upset about ‘where the culture is going’. One faction is celebrating the rise of LGBT rights, while another is fighting for the survival of ‘the family’. One side is fighting to keep pro-choice funding, the other is fighting for stricter pro-life laws. One group hails technology as a panacea, while another bemoans the loss of traditional values. And that’s before we even get onto politics proper. It seems everyone has strong views in one way or another about the nature of society. But can anybody do anything about it?

Line drawings © Jay Johnson 2019

Three dead philosophers say yes, and even tell us how. They talk in terms of ‘cultural hegemony’, which means a set of ideas or a worldview having a predominant influence in a culture. In simple terms, the cultural hegemony is what the majority of people in a given culture assume is right, good, and true – usually without even questioning it. The challenge is taking theoretical insights about cultural hegemony and making them practical. So let’s start by taking a brief look at the ideas of these three twentieth century philosophers – Louis Althusser, Antonio Gramsci, and Karl Mannheim.

The French philosopher Louis Althusser (1918-1990) led a renewal in Marxist scholarship in the 1960s-70s by rereading Marx’s works in opposition to its Stalinist misinterpretations. Althusser is best known for developing the concept of ‘ideology’, which he understood as “the imaginary relationship of individuals to their real conditions of existence” (Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, 1971, p.162).

Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) led the Italian Communist Party in the 1920s before Mussolini’s government sent him to prison for speaking against fascism. There he wrote the Prison Notebooks (1929-1935), in which he developed the idea of cultural hegemony. He died still in prison after eleven years, at the age of forty-six.

Born in Hungary, Karl Mannheim (1893-1947) pioneered the sociology of knowledge in the 1920s-30s. Mannheim argued that no knowledge can be context-free. Rather, each person “confronts the world and in striving for truth constructs a worldview out of the data of his experience”, leading to distorted or at least limited thinking (Ideology and Utopia, 1936, p.26).

These three big ideas – ideology, cultural hegemony, and the sociology of knowledge – when joined together will help us answer two big questions: Why is our culture the way it is? And what can we do about it?

The Big Picture

Gramsci described hegemony as the way in which the ruling class, the elite, in any society maintains its position of power and privilege by promoting its values and beliefs through the institutions it controls, so suppressing any popular desire for change.

Consequently, for many ‘hegemony’ is a dirty word, carrying connotations of the abuse of power. But it is also possible to view it more neutrally, as simply the process by which we, the members of a certain culture, form our assumptions about reality, which, once formed, exert influence on behaviour, policy, and laws. Despite its powerful influence, hegemony is never final in the same way that culture is never final. Culture is always interacting with various influences that keep it in a state of flux. Once hegemony can be challenged, and eventually replaced, by another, and it can happen in a perfectly peaceful way.

Suppose one point of view exercises virtually uncontested influence over a culture, and of course is reflected by and perpetuated by society’s various institutions. At some point in time, a small reform movement develops and challenges the dominant culture. In the end, if successful, the small reform movement has itself become the dominant culture. Let’s take the example of education to illustrate this process. Once the preserve of tutors and monks, today most developed countries prefer a mass schooling model for education. Children travel to large buildings to be taught in classes with other children of the same age by professional teachers. This is now the dominant culture, although it was also only a small reform movement two hundred years ago. However, within this dominant culture, many families have now grown dissatisfied with what they see as a ‘production line’ approach to education. They want a more organic, individual-oriented approach. So they start a home-based model, based on the teachings of John Holt or Charlotte Mason. The movement is small, but it’s growing. It starts networking with other families that want the same thing. As this home-school movement grows, this creates a phase of struggle between the two sets of cultural values. If they’re successful, then after a period of struggle, the home-schooling model will become an accepted, or even mainstream, alternative to mass schooling – and with it establish a new set of cultural values.

This model of the evolution of cultural hegemony does not come from Althusser, Gramsci, or Mannheim individually. Rather, it synthesises their insights about how culture forms and reforms to argue for the possibility of a non-deterministic type of social change: change that doesn’t just happen, but is chosen and deliberately promoted. In other words, this model says how small groups of dedicated individuals can change economic, political, and cultural norms in a way that is flexible and amenable to various types of influences. This is in contrast to the economic determinism often associated with Karl Marx, the political determinism often associated with Carl von Clausewitz, or the cultural determinism often associated with Max Weber. In all these cases, the named dimension holds decisive influence over the other two, such that the other two dimensions of human life cannot in the end affect what will happen in the determining dimension. In reality no single dimension of human life is deterministic. This is good news for those without power – those not occupying seats of economic, political, or cultural leadership – because it means the path of development of society is not set in advance. It implies that a small group of concerned and committed individuals can begin the cultural change process, which moves out to the economic dimension by its ability to multiply and sustain itself, exerts influence on the political dimension, before thoroughly influencing the cultural dimension. I might summarise the advice of this article in the words of the anthropologist Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world” (Earth at Omega: Passage to Planetization by Donald Keys, 1982, p.79).

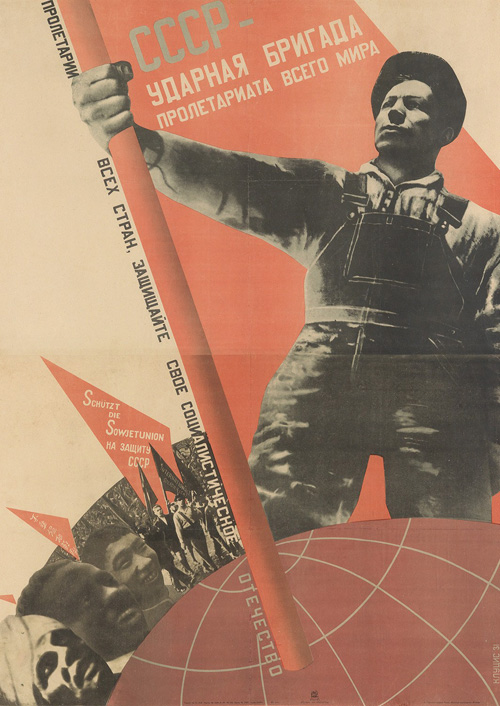

‘The USSR is the Shock Brigade of the World Proletariat’ by Gustav Klutsis, 1931. Klutsis was killed in one of Stalin’s purges soon afterwards.

How Did Our Culture Get This Way?

On this model, a cultural hegemony forms through three stages: its supporters acquire some power; they get institutions on board; and then let the institutions spread the culture.

Power is a natural and inevitable part of human society. Although philosophers such as Marx wanted society to ultimately move beyond power dynamics, someone, or some group, is always more powerful than another. Like everyone else, those in power hold a set of cultural values, whether they’re aware of them or not. Without decisive intervention, those cultural values will eventually become the dominant cultural values. Naturally, those in power want to extend their vision of a better world – that is, their culture. To do this, they must get key institutions on board: families, religion, education, media, and social leaders. Althusser called these institutions ‘Ideological State Apparatuses’ because they’re the instruments that shape people’s thinking (Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, 1968, pp.127-188).

But how does one get families, religion, education, media, and social leaders on board? Give them something they want, in order to get something in return. All institutions want some kind of power, even if it’s only for their own survival. For example, families want the power to make a living. Religions want the power to practice freely. Leaders want the power to make a difference. So they are all to some extent incentivised to comply with those already in power. As much as is possible, they agree to the culture prescribed by those in power. Both sides gain.

It goes deeper. Incentives can buy votes for politicians and approval for a businesses; but what about when the incentives run out? The long-term plan for power is not built on providing incentives but on establishing cultural values. Values are the decision-making criteria of our lives. If I can change your values, I no longer have to buy your vote. So how do we change values? Through ruling intellectuals.

Gramsci describes two types of intellectuals: ruling intellectuals, who maintain the status quo for those in power, and organic intellectuals, who challenge the status quo. According to Gramsci, ruling intellectuals are the ‘deputies’ of the dominant culture (Selections from the Prison Notebooks, 1971, p.12). For example, if those in power are pro-capitalist, the ruling intellectuals will write textbooks that highlight the achievements of open markets and deconstruct the failures of socialism – or vice versa for a pro-socialist context. Althusser goes so far as to say that “no class can hold State power over a long period without at the same time exercising its hegemony over and in State Ideological Apparatuses” (Lenin, p.146).

According to our philosophers, the last stage of establishing a hegemony – spreading a culture – is the easiest to achieve. Winning power requires fighting. Winning institutions requires negotiation. Winning individuals requires only their consent to the values of the institutions. Most of the values of most individuals are unconsciously absorbed. We do not often question the values of our culture (for example, human rights, individualism, materialism) because, in the words of Gramsci, they have become ‘common sense’ (Selections, p.134). For example, we are pro-choice or pro-life usually because that is the stance of our family or religion.

Althusser describes the process of accepting the culturally hegemonic institutional line as moving from being ‘free subjects’ to willingly accepting subjection ‘all by [one’s] self’ (Lenin, p.182).

How Can Cultural Values Be Reformed?

If this is how we got our culture, how can we change it?

Anybody can change culture; but only if they can spread their ideas to other ‘organic intellectuals’ – thinkers also holding culturally unpopular opinions.

Who could qualify as an agent of cultural change? Anybody with a Facebook account, podcast, or YouTube channel. It’s easier today than it has ever been for anybody to change culture.

Cultural values are reformed in three stages: get people thinking, get people together, and get institutional change.

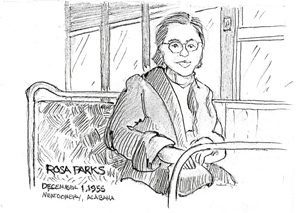

To begin, some type of critical incident is usually necessary to create awareness of and then to question ‘the philosophy of common sense’. Mannheim describes this as an unveiling of our ‘false consciousess’ – that is, the uncritically-accepted assumptions of the dominant culture – through self-reflection (Ideology and Utopia, pp.62-84). When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in 1955, her action became a critical incident inciting the reflection of an entire culture. Or in 1787, the British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson met the Member of Parliament William Wilberforce and showed him the handcuffs, shackles, and branding irons used in the slave trade. This, along with Clarkson’s essay on slavery, was enough to get William Wilberforce thinking, and redirect his efforts for the next thirty-five years to work to make the slave trade illegal.

In stage two, awareness must spread to a sizeable minority through the activity of the organic intellectuals. Gramsci says that when enough organic individuals network together, they form a new voice, loud enough to challenge the ‘philosophy of common sense’. For Mannheim their collective voice presents a possibility of what could be – a ‘utopia’. Martin Luther King Jr. called it having a dream. Many activists are doing this today through social media – selling a dream. (This may also explain the recent popularity of books on how to make ideas spread: for example Made to Stick (2006), Influencers (2007), Start with Why (2009), All Marketers are Liars (2009), Contagious (2013), The Small Big (2014).)

In cultural reform stage three, ideas must change institutions – or create influential new ones. It’s not enough to have ten trillion likes on Facebook; your ideas must change people’s behaviour. It’s not enough to get a hundred organic intellectuals talking about them, either: your ideas must create policy change. Unfortunately, this stage often drags on for decades. For example, in 1929, the German doctor Fritz Lickint published a formal study that linked smoking with lung cancer. But it was not until 1964, after seven thousand more studies had been published, that the US Surgeon General’s office made its first public announcement on the dangers of smoking.

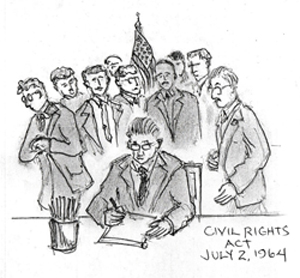

Let’s return to the civil rights movements in the US and the UK I cited, to consider the step from gaining popularity (stage two) to policy change (stage three). Martin Luther King, Jr. was a success not because he and his followers persuaded 250,000 people to march on Washington in 1963, but because he and they convinced President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the Civil Rights Act in 1964. William Wilberforce was not a success in 1792 because he and his followers had collected 390,000 signatures demanding the abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire. He was a success in 1807, when the slave trade was abolished; and further in 1833, when slavery itself was abolished. An idea must re-align the behaviour, policy, and laws of institutions in order to have a widespread and lasting effect on culture. Once embodied in institutions, the institutions themselves start doing the work of socialising individuals. Or in Althusser’s terms, institutions are the ‘material existence’ of culture which ‘recruits’ individuals and ‘transforms’ them into their idealised culture (Lenin, pp.165, 170).

The process of cultural reform is never finished. Power is always being negotiated. Someone is always fighting to maintain the status quo – just as a politician in power must still be thinking about maintaining popularity for the next election.

Culture is not something static – people are always changing culture. So the real challenge, after all, may not be how to change culture. Our three philosophers have given us a roadmap for how to do that. The real challenge may be changing culture with humility and civility, knowing that everyone is upset about something in the culture, and that many people are doing their best to make this a better world.

© Kevin Brinkmann 2019

Kevin Brinkmann is the author of The Global Leader™, a leadership development programme used by Fortune 500 companies and the United Nations. He can be reached at kevinbrinkmann.com.