Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Bertrand Russell & Common Sense for Savages

Stephen Leach considers what Bertrand Russell thought about common sense & reality – and how the one does not necessarily show you the other.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) believed that reality is knowable, but ordinary language is apt to deceive us as to its nature. For example, an assertion about ‘the present king of France’ is understandable, but ‘the present king of France’ does not denote an entity in the real world, and so anything said about ‘him’ that implies his existence will be false. Misleading assertions such as these are likely to entangle the unwary philosopher; but, Russell believed, an ideal language, discovered through careful logical analysis and rigorously applied, would prevent us from being deceived.

At the turn of the twentieth century he set out to formulate this ideal language, at the same time attempting to demonstrate that mathematics is reducible to logic and that both mathematics and logic refer to real entities. Although Russell’s ultimate ambition was never achieved – reality, logic, and mathematics remain separated – he made enormous contributions to the study of logic along the way, and also came some way towards his ideal language, by helping to develop predicate logic. Moreover, on the way, Russell helped inspire a new way of doing philosophy. He is one of the Founding Fathers of the analytic tradition, one of the main characteristics of which, to this day, is an awareness of the deceptiveness of language. There is a determination in the analytic tradition to be clear and unambiguous – a determination that some might argue is sometimes (or often) carried a bit too far. An essay written with determinedly unambiguous language does not always make for the easiest of reading. However, in Russell’s case, in both his technical writings on logic and in his more popular works, the clarity of his language is matched by the elegance of his expression.

Given his view of the misleading nature of ordinary language, one might expect Russell to have been extremely wary of common sense, which after all is invariably expressed in ordinary language. However that is not quite Russell’s view. In fact, as A.J. Ayer points out, a consistent characteristic of Russell’s career is that he looked for reasons for accepted beliefs: “In the course of his long career, Russell… has held quite a large variety of philosophical opinions… But the fact is that, while he has fairly often changed his views on points of detail, his approach to philosophy has been remarkably consistent. His aim has always been to find reasons for accepted beliefs, whether in the field of mathematics, natural or social science, or common sense” (Metaphysics and Common Sense, 1969, p.179). That is not to say that in metaphysics Russell regarded accepted beliefs as a criterion of truth. Far from it: he fully realised that accepted beliefs and conventional wisdom might simply reflect a contingent environment:

“The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the cooperation or consent of his deliberate reason.”

(Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy, 1912, p.91)

Common sense may supply a starting point, but is not a criterion of truth.

However, in his journalism on social and political questions – which he sharply distinguished from his more technical philosophy – Russell was less critical: “I am prepared to admit the ordinary beliefs of common sense, in practice if not in theory” (Sceptical Essays, 1928, p.12). His journalism contains plenty of approving and unquestioning references to common sense – including Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare (1959), in which Russell presents himself as the champion of common sense. In this respect, in his journalism Russell followed in the footsteps of Thomas Paine, whose pamphlet Common Sense (1776) accelerated the advent of American independence. What Paine with false modesty told his readers was common sense was not actually common sense until they read his pamphlet and were convinced it was. The same applies to Russell. He claimed to speak on behalf of common sense, but, in doing so, he was doing no more than attempting to prejudice his readers in his favour. It’s a rhetorical move which has been pervasive in political debate ever since the Enlightenment.

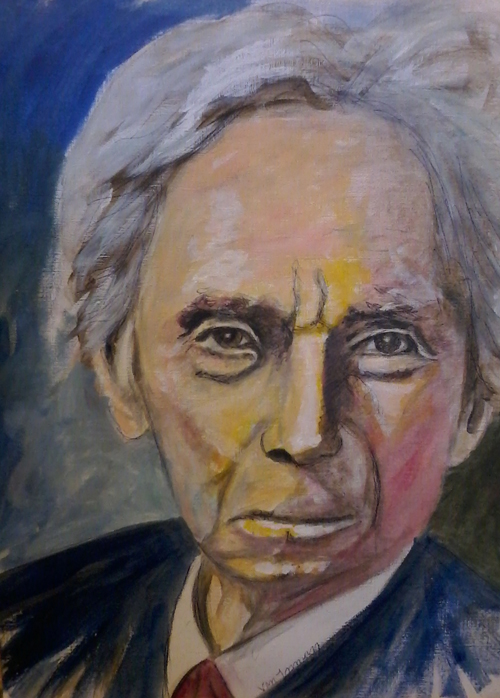

Bertrand Russell

Russell portrait © Clinton Inman 2019. Facebook him at clinton.inman

Metaphysical Savaging

However, this tolerance of common sense as at least providing the starting point of an investigation does not seem to chime with one of the most famous of Russell quotations: “Common sense is the metaphysics of savages.” Intrigued by this disparity, I have searched for the original source of this quotation. It seems to first occur not in Russell’s writings, but in a paraphrase of Russell’s views by the American theologian Douglas Clyde MacIntosh, in 1915.

MacIntosh was commenting on the views expressed in Russell’s book Our Knowledge of the External World (1914). Two years earlier, in The Problems of Philosophy, Russell had argued that we infer the existence of the physical world from our sense experiences. That is to say, the existence of the physical world is accepted because it provides the best inferred explanation of our experiences. But in 1914, in Our Knowledge of the External World, Russell argues that objects are not inferred from but are actually constituted of actual and possible sense data. That is to say, he argued that physical objects are, in fact, no more than collections of actual and possible immediate sensory impressions. Russell’s earlier view was dualist, in that it acknowledged a fundamental difference between mental content and the physical world. His new view was monist, in that it acknowledged no such gap: the world is made of just one type of stuff. This tallied with Russell’s view that all knowledge derives from experience, and it is also attractive because, all else being equal, a simpler explanation is preferable to a more complicated explanation (Ockham’s Razor). Russell argued that to infer the existence of the physical world independently of our collections of actual and possible sense data is an unnecessary step. An independent physical world may be the common sense view, but it is unnecessary. Thus, looking back to his earlier view, Russell became dismissive of common sense: “Physics started from the common-sense belief in fairly permanent and fairly rigid bodies… This common-sense belief, it should be noticed, is a piece of audacious metaphysical theorising… We have thus here a first departure from the immediate data of sensation… probably made by our savage ancestors in some very remote prehistoric epoch” (Our Knowledge of the External World, p.107). Russell also believed that his new view avoids the problem of radical scepticism – the problem of not being able to know whether the physical world actually exists or whether it is only created by the mind. For, he argued, on his new view there is no reason to believe that sense data cannot exist when they are not perceived.

In response, MacIntosh made it clear that he much preferred Russell’s earlier explanation of the physical world. In MacIntosh’s opinion, this earlier explanation may have had problems, but it remains, after all, closer to common sense and so should not be so quickly rejected. He summarised Russell’s metaphysical move from 1912 to 1914 as follows:

“The common sense notion of fairly permanent things, recognised as being a construction, not a datum, is now rejected as ‘the metaphysics of savages’. By the use, it is claimed, of ‘Occam’s razor’, the inferred entities of common sense are replaced by compounds, or classes, or series of sense-data… The main criticism to be made against Russell’s philosophy at this point is that he has swung from absolute dualism to an absolute monism in epistemology, because he saw no other way of escape from an almost total agnosticism with reference to the physical world. The desperateness of his former condition is reflected in the desperate remedy to which he has had recourse, cutting himself off absolutely from common sense, for which offence he salves his conscience by applying to the common sense view the epithet, ‘metaphysics of savages’.”(Douglas Clyde MacIntosh, The Problem of Knowledge, 1915, p.243)

It is easy to see how the confusion over the quotation occurred, for a reader of MacIntosh might naturally assume that the phrase in inverted commas is Russell’s. But, these are not inverted commas in the sense of quotation marks; they are actually ‘scare quotes’.

Admittedly, what Russell says in Our Knowledge of the External World does amount to the idea that concerning the nature of reality, in this instance “common sense is the metaphysics of savages” – but he does not claim that all common sense beliefs should, by their very nature, be immediately ruled out of court as intellectually primitive. Common sense may at least supply a starting point.

In his political campaigns, Russell was prepared to present himself as the spokesman of common sense. And in his philosophical work, Russell may not have been quite as dismissive of common sense as the famous ‘quotation’ would have us believe.

© Stephen Leach 2019

Stephen Leach is honorary senior fellow at Keele University and co-editor, with James Tartaglia, of The Meaning of Life and the Great Philosophers (Routledge, 2018).