Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Kant’s Opus postumum

Terrence Thomson wrestles with Kant’s unfinished work to ask what we should expect from philosophy books.

I have recently been immersed in trying to understand Immanuel Kant’s last text, his so-called Opus postumum. It is composed of sheets (or ‘fascicles’ or ‘convolutes’) that Kant began writing in the mid 1790s, continuing to a year before his death in 1804. It is not easy to summarize, but I can start by observing that it contains a vast array of thoughts, notes, drafts, and marginalia at varying levels of completion. Attempting to make sense of Opus postumum presents an especially challenging task since it throws up all manner of perplexing material, which sometimes morphs the philosophy in the three Critiques [of Pure Reason, of Practical Reason, and of Judgement, Ed] that form the pillars of Kant’s thought; sometimes does not relate to it at all; and sometimes contradicts it entirely.

At its root (if we can talk in such a way about Opus postumum) is a work Kant provisionally titled Transition from the Foundations of Natural Science to Physics, which attempts to construct a bridge to empirical physics from the ‘special’ metaphysics of nature partially explored in his Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science of 1786. Whilst this is the initial project Kant focuses on, as the fascicles progress various topological shifts take place. Kant begins to rework his whole theory of matter into a more precise element of the metaphysics of nature, capable of taking into account the density of matter alongside attractive and repulsive forces. Apparently this reworking was a response to a problematic part of Metaphysical Foundations that was pointed out to Kant after its publication.

If this seems like a strange diversion for Kant, it pales in oddity to his discussion of ether in the central fascicles. Labelled Übergang 1-14, these fascicles contain an attempt to ‘transcendentally deduce’ an invisible yet material medium through which all matter travels. This dispersed ‘world material’ (which was not an uncommon conjecture in eighteenth century natural science) is one of the most discussed parts of Opus postumum, since it challenges what Kant scholars previously held his method of transcendental deduction to be capable of. Moreover, the idea of ether seems contradictory – it is material and yet invisible; it is everywhere yet impermeable – but Kant nonetheless affirms that a transcendental deduction of it is possible, even necessary. This is only one of the many complexities jutting out from Opus postumum. There are plenty more.

I must admit that this is only one interpretation of what is happening in Opus postumum. Indeed, every one of the few theses put forward about Opus postumum has been regarded by Kant scholars as highly debatable. There aren’t that many: as of 2020 only three English monographs and a handful of journal articles. It seems that we do not know how to begin understanding such a curious amalgam of material. Why is this the case?

Ever since some fragments were first published in journals in 1882, Kant’s Opus postumum has been considered something of an interloper in his body of writings. Terms such as ‘senility,’ ‘marks of decrepitude’ and ‘Kant’s weakening faculties’ were common even in the reviews of the first Akademie Ausgabe version of Opus postumum (in two volumes, in 1936 and 1938). Yet between the fascicles being found on Kant’s desk and the publication of the Akademie edition, 132 years had elapsed, and the loose pages had already suffered some complex, even catastrophic, events, including being dropped in a puddle and coming out of order, forever leaving us in the dark about how they should be arranged. Kant did not number his sheets. Once they were published, no reviewer failed to note the eerie, unknown nature of the new Kantian landscape, and most opted to simply not take it seriously at all. One reviewer, Kuno Fischer, famous for how critical he was toward Opus postumum, said, “one may doubt the value of [Kant’s last] work… if one considers both the frail state in which Kant was at the time and the completion to which he himself had brought the philosophy he had founded” (Quoted from Kant’s Final Synthesis, Eckart Fӧrster, 2000, p.49). The clear implication was that the manuscript is a waste of time, not to be bothered with, and that the real scholarship is in studying Kant’s previous work.

These points of view have cast a deep shadow over the Opus postumum.There have also been brilliant attempts at reintegrating Opus postumum into Kant’s philosophy (Gerhard Lehmann, Burkhard Tuschling, Vittorio Mathieu and Erich Adickes provide some of the most detailed scholarship), as well as fantastic hermeneutical proposals designed to critically reconstruct it. But these attempts have all been dogged by the subterranean negative idea that Opus postumum is simply not worth the trouble; that it is best to stick to the Kantian edifice we know and love.

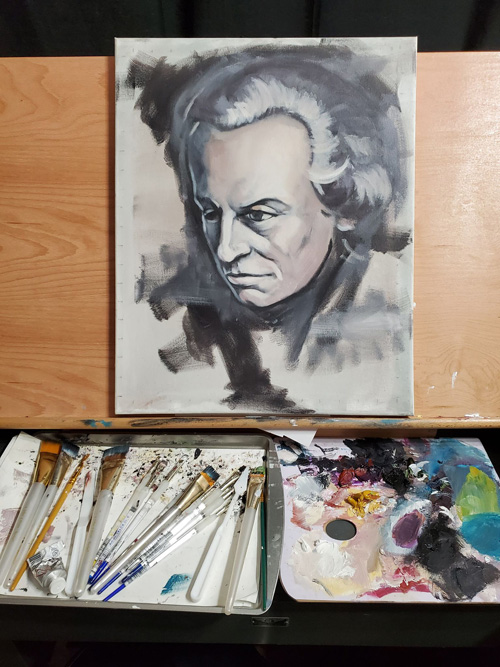

Unfinished Kant © Woodrow Cowher 2019. Please visit woodrawspictures.com

However, more recently, many scholars have cast off this prejudice and returned to Opus postumum in a sustained attempt to investigate what’s going on and how it may provide a key to understanding Kant’s previous work in a new light. The three monographs in English fall under this category: the aforementioned Eckart F ӧ rster’s Kant’s Final Synthesis in 2000, Bryan Wesley Hall’s The Post-Critical Kant in 2015, and Oliver Thorndike’s Kant’s Transition Project and Late Philosophy in 2018.

All three are fine scholarly works, destined to contribute to the future reception of Opus postumum. Yet it cannot be denied (and I don’t think anyone does deny it): Opus postumum is filled with problems and contradictions. Even decisions around editorial form are problematic; how do we decide whether to keep the deletions and correct the 'mistakes'? Yet recent scholarship on the text, particularly Hall’s masterpiece The Post-Critical Kant, suggests that there is a unique thread running through Opus postumum, and if a few simple rules are followed we can find in the text an argument that makes sense and even convincingly critiques the philosophy of Kant’s three Critiques.

Accordingly, Hall gives four rules for a ‘good interpretation’ of Opus postumum. First, be consistent with the text; second, make Kant consistent with himself; third, be philosophically plausible; and fourth, give Opus postumum the respect it deserves – after all, Kant considered it the ‘keystone’ of his philosophy.

These rules are evidently excellent guidelines for navigating through any complicated text, not only Opus postumum. But something about them bothers me. Why should we make Kant consistent with himself? Why should we erase any trace of contradiction? I cannot recall coming across a similar set of rules for reading other philosophical books; nor do I recall the need to adopt similar rules for Kant’s other work – even the notoriously difficult Critique of Pure Reason, which contains contradictions too. So why the need for such rules with this ‘keystone’ of Kant’s philosophy?

Before staking a possible answer, it is worth making a few more observations about Opus postumum as a book. To begin with, it is unfinished, which means that we interrupt Kant in his thinking process. So whereas in his Critique of Pure Reason, for example, we have an orderly layout presenting the argument – for instance, a Doctrine of Elements and a Doctrine of Method; or the division of the argument into a Transcendental Aesthetic, Transcendental Analytic, Transcendental Dialectic, and so on – there is no equivalent layout in Opus postumum. We catch Kant in the act, so to speak. This gives rise to the enormous difficulties in interpreting the text; but it also inadvertently gives rise to enormous opportunities. Instead of ascertaining Kant’s analysis and reconstructing it in our own conference papers, essays and books, we join him in thinking.

This, inevitably, is a painful experience. In an oft-quoted letter, Kant remarks that writing the fascicles was “a pain like that of Tantalus” (Correspondence 12:257): so it’s no wonder that we too also feel pain when we try to reach out and grasp the core ideas of Opus postumum, only to find that we have grasped nothing. This pain is provoked by Kant’s repetition, restatements, over-meticulous descriptions, the sudden shift from one subject to another, deletion of important sentences, paragraph-long sentences, irrelevancies (for example, shopping lists, to do lists, dinner party guest lists…), and the general disorder of the work. But, this pain is actually a ticket into a remarkable world: it is an invitation to think in an authentic way with Kant, warts and all. Opus postumum truthfully mirrors the act of thinking: it misses nothing out, not even the myriad repetitions, deleted passages, and contradictions. In the same way, rarely are our own thoughts immediately clear. Rather, they are often repetitive, contradictory, multifaceted, and unstructured, until we actively organize them, redraft them, resculpt them, polish them, and so laboriously make them clear. It is even rarer to be publically presented with raw thinking. On the contrary, the organization of ideas, especially when presented in book format, directly influences our notion of what thought is. So in a book of philosophy, we are typically not invited to think with the author, only to think about his or her perfected thoughts. Opus postumum is the opposite of this standard format, and with it we are presented with nothing less than a challenge to how we read a philosophy book. It unintentionally demonstrates that the expectation of a smooth, linear, rational line of argument in a philosophy book (analytic and continental) is so ingrained, that when we encounter something authentically different, the immediate reaction is to overlook it or discount it. And Opus postumum is not perfected; nor does it contain a smooth, linear, rational line of argumentation. Rather, it is rough terrain – non-linear, and jutting out in many directions.

This brings us to a possible answer as to why we need rules for interpreting Kant’s last text. Perhaps the problem does not lie in Opus postumum at all, but in our expectation of it as a book. Perhaps we are so used to philosophy books presenting their arguments in a smooth way that when we’re confronted by something irregular, our instinct is to try to make it fit, to transform it into a work with a rational arc. Perhaps without rules we are left with merely the raw contradictions of the book, a scattered tangle of arguments without conclusions, and conclusions without arguments. But so what? Why can we not read Opus postumum in this way, respecting its contradictions and admitting that, yes, it is a rough ride; yes, there are problems with it; and yes, it is perhaps one of the most difficult documents by one of the most difficult philosophers; but also, yes, it challenges us to think for ourselves in the most rigorous way. It challenges our expectation of what a philosophy book is and what a philosophy book is supposed to do, by showing us what a philosophy can be, and by doing what a philosophy book is not ‘supposed’ to do.

Whether we continue to try and fit this irregular oddity into the regular framework of philosophical argumentation, or whether we try to account for the contradictions and problems in a different way remains to be seen. But I’m sure of one thing: if ever Saul Bellow’s words were appropriate when he wrote, “I have always been a believer in an unfinished work to keep you alive” (Ravelstein, 2000), they are so with regard to Kant and his Opus postumum.

© Terrence Thomson 2020

Terrence Thomson is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy in Kingston University, London.