Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

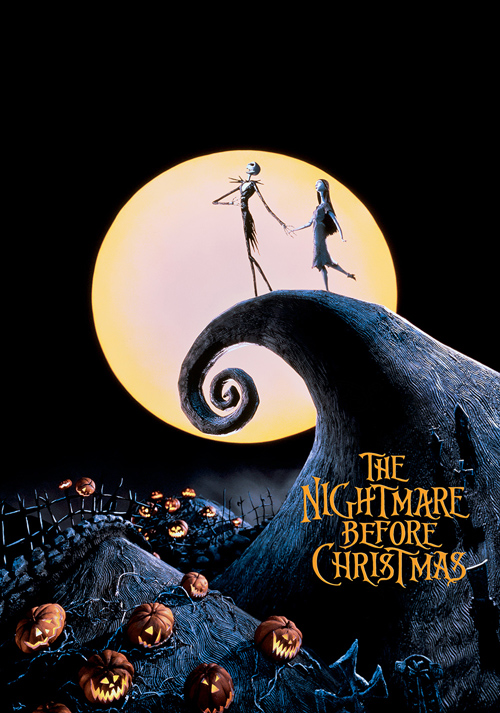

The Nightmare Before Christmas

Siobhain Lash argues that you can sometimes be to blame even when you couldn’t have done differently.

If free will does not exist, what implications does this have for our ethical behavior, specifically for moral responsibility? And what does determinism – the idea that you could not have done otherwise than what you actually did – really imply for moral responsibility?

The widely-held Principle of Alternate Possibilities states that a person is morally responsible for what he has done only if he could have done otherwise. Thus if someone is said to have a level of control over their actions and a choice between two options – to do or to not do something – then they can be considered as morally responsible for their actions. Conversely, if they lack a real ability to choose between two options (for instance because determinism is true) then they cannot be considered as morally responsible for their actions. This includes if a person was being influenced by external or internal force. For instance, if I hold a gun to your head and tell you to open the bank vault, you are not morally responsible for doing so.

In his 1969 essay ‘Alternate Possibilities and Moral Responsibility’, the philosopher Harry Frankfurt famously rejected the Principle of Alternate Possibilities, deeming it to be false and arguing that sometimes “a person may well be morally responsible for what he has done even though he could not have done otherwise” (p.185). Frankfurt illustrates this with an example about a manipulative control freak called Mr Black. Mr Jones has a choice between two courses of action, A and B, and Black has reasons for wanting him to choose A. But Black doesn’t want to show his hand unnecessarily. He waits to see which way Mr Jones is inclined to go. If Jones looks like choosing A, all well and good. If Jones looks like choosing B then Black will take a hand, expertly manipulating the situation to guarantee that Jones chooses A. Mr Jones knows nothing of this and after some thought chooses A. Now, we know that Jones had no real control over the outcome – one way or another, he was going to do A. But Jones doesn’t know that; he made his choice without any awareness of Black. Therefore, says Frankfurt, Jones bears moral responsibility for his action even though he could not have done otherwise. Therefore Frankfurt thinks the Principle of Alternate Possibilities should be replaced with the subtly different principle that “a person is not morally responsible for what he has done if he did it only because he could not have done otherwise.”

I will attempt to illustrate Frankfurt’s point and further dispel the idea that determinism and moral responsibility are mutually exclusive through the example of Jack Skellington in Tim Burton’s 1993 movie The Nightmare Before Christmas. Jack is going to demonstrate moral responsibility in a case where he could not have chosen otherwise: in this particular case, in relation to him not being able to choose otherwise than to ruin Christmas. I will argue that because of the reason behind his actions, Jack Skellington is morally responsible for ruining Christmas even though he could not have done otherwise, given the circumstances. To do this, I will examine what would make it impossible for Jack to have done otherwise.

It’s Christmas, but not as we know it.

Film images © Disney 1993

The Plot

Frankfurt’s rejection of the Principle of Alternate Possibilities says that even when a genuine alternative choice to do otherwise is not available, that person is still morally responsible for their actions, if the reason for their actions is their own.

Jack’s underlying goal or reason for action in The Nightmare Before Christmas is to find a sense of fulfillment. Jack is de facto leader of Halloween Town. Coming down from a high from the success of yet another Halloween, Jack wanders into the forest to gain some clarity. There he stumbles upon seven doors, each with a shape corresponding to a holiday, such as a heart for Valentine’s Day, an egg for Easter, and a shamrock for St Patrick’s Day. Going through one of the doors, Jack finds himself in Christmas Town and soon becomes enthralled with the unfamiliar holiday, and obsessed with celebrating it.

Jack later shares his findings with the monstrous citizens of Halloween Town, and as their leader, tells them to replicate Christmas-themed concepts and activities, such as giving presents and carol singing. He also sends a trick-or-treating trio, Lock, Shock, and Barrel, to kidnap ‘Sandy Claws’, so that he can take over Christmas in Christmas Town in Santa’s stead. He orders them to keep Santa safe; but they deliver Santa to Oogie Boogie instead. Sally, Jack’s love interest, warns Jack that his plan will end in disaster; but determined to find a sense of fulfillment, Jack dismisses Sally’s warning.

As Sally predicted, trouble ensues. Jack’s Halloween-themed Christmas gifts assault and frighten the citizens of Christmas Town. His sleigh pulled by skeletal reindeer scares them and arouses suspicion towards ‘Santa’, so the military is called in. Jack is shot down, causing him to crash into a cemetery, where he reflects on the disasters he has unleashed. Downtrodden but undeterred, Jack sets out to find the real Santa and rescue him from Oogie’s lair. Jack apologizes to Santa for his actions that caused Christmas to be so disastrous, before Santa leaves to fix things. After Santa finishes fixing Jack’s catastrophe, as a gift, he makes it snow in Halloween Town. This allows Jack to finally feel a sense of fulfillment. Despite his having ruined Christmas, the events have reinvigorated his love for Halloween.

Jack & Sally

The Argument

Jack’s circumstances and abilities allow him to take over Christmas. However, these circumstances include a set of conditions that preclude him from running it successfully. As a result Jack seizes control of Christmas, but ruins it.

Frankfurt states, “A person may do something in circumstances that leave him no alternative to doing it, without the circumstances actually moving him or leading him to do it – without them playing any role, indeed, in bringing it about that he does what he does” (p.186). Jack’s circumstances preclude him from being able to take over Christmas successfully. However, these same circumstances do not play a role in his decision to take over Christmas. Neither do the possible consequences of his action of taking over Christmas influence his inclination to do so. He does so just because he wants to, not because he knows he will be successful, or not.

Jack assigning his citizens to act (for example, by singing carols or kidnapping Santa Claus) and the ability to make things that emulate Christmas (for example, red suit, sleigh, presents), are necessary conditions for Jack to be able to take over Christmas. Jack needs to have presents to deliver to the children in Christmas Town, just like Santa, and a sleigh to be able to get around Christmas Town in a swift manner, as well as to look similar to the real Santa Claus. These are all necessary conditions for Jack to be able to launch his Christmassy coup. However, Jack enlisting his Halloween citizens to enact Christmas traditions does not provide sufficient conditions for Jack to be successful at running Christmas. What’s more, Jack’s circumstances – being the Pumpkin King, being spooky, being the leader of Halloween Town – precluded him from being able to choose otherwise. That is, Jack could not have chosen to not ruin Christmas. Acting spooky is all he and his fellow citizens know, even when attempting to emulate customs and actions that are inherently unspooky, such as singing Christmas carols, giving presents, and decorating Christmas trees. It was always going to end badly. Thus, having taken over Christmas, Jack had no choice other than to ruin it.

In saying that, Jack nevertheless is more than the sum of his circumstances. That is to say, he did not take over Christmas only because he is the spooky Christmas-obsessed Pumpkin King etc; rather, he did so because he wanted to do so, in his search for personal fulfillment. Thus, Jack did have some sort of choice (free will) about taking over Christmas, although he then had no choice but to ruin it.

Under these conditions, according to Frankfurt’s reasoning, Jack should be considered morally responsible for ruining Christmas as, despite his circumstances making it impossible for him to avoid ruining it, Jack did what he did because he really wanted to. To requote Frankfurt, “a person may well be morally responsible for what he has done even though he could not have done otherwise” (p.185).

In The Nightmare Before Christmas, it is clear that Jack Skellington is not able to do otherwise than to ruin Christmas. However, Jack takes charge of Christmas because of his own inclinations. Therefore, he is morally responsible for ruining Christmas, even though he could not have done otherwise. So, as Frankfurt suggests, the Principle of Alternate Possibilities does not hold up, because the ability to choose otherwise is not necessary for allocating moral responsibility.

© Siobhain Lash 2020

Siobhain Lash is a PhD student in Philosophy at Tulane University in New Orleans.