Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Editorial

Time and Being

by Rick Lewis

“I wasted time, and now doth time waste me;

For now hath time made me his numb’ring clock;

My thoughts are minutes, and with sighs they jar

Their watches on unto mine eyes, the outward watch,

Whereto my finger, like a dial’s point,

Is pointing still, in cleansing them from tears.”Shakespeare, Richard II

Near the end of Shakespeare’s play Richard II, the king, unthroned by his rival Bolingbroke, languishes in a dungeon awaiting his fate and contemplating the nature of time. Such circumstances give even kings the time and inclination to be philosophical. Still, Richard’s musings touch on a deep and fascinating philosophical problem – the interrelation between time and personal identity.

The question of how the passage of time affects who we are is one of those philosophical questions that we bump up against in everyday life. A lot of folk think about it every time they look in the bathroom mirror and spot another wrinkle or grey hair. Time doth waste us indeed, and this hard fact is unlikely to change any time soon. I’d have said this was an immutable law of nature, though just as we were going to press news came through that researchers in Israel appear to have reversed the human aging process at the cellular level by using a form of oxygen therapy. In any case, we all change over time but most of us like to think we remain in some sense ‘the same’ person despite that. Something is left in you of the child you once were and something in you prefigures who you may become in the future. How can we can claim to be the same individual despite changing our appearance, our behaviour, our molecular composition gradually yet drastically over the years? Perhaps Thomas Reid and John Locke were right, and it is a continuing thread of memory connecting the different stages of your life that makes you the same person.

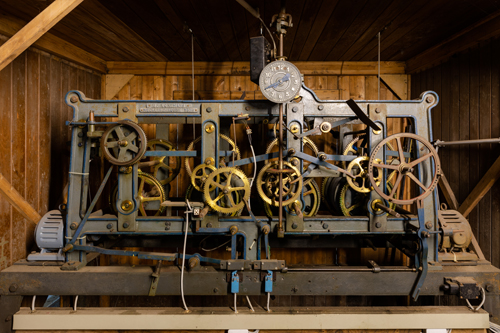

But in a universe of physical causes and predictable effects, which then themselves are causes of other effects, following each other endlessly and mechanically like an intricate clock unwinding its spring over billions of years, we may wonder whether we have any freedom or if the appearance of choice is just that – a mere appearance. If we are free to choose our actions, can those freely chosen actions change the sort of people we become – affect our individual identity? Aristotle certainly thought we could actively work to become better people – that is the basis of his virtue ethics – and the extent to which we can fundamentally and consciously alter our own identities is another interesting question. If free will is an illusion and we don’t have the freedom to act differently then in what sense can we be held morally responsible for our actions?

In our themed section on Time, Identity and Free Will, our contributors wrestle with these three intertwined philosophical topics. They explore most of the questions I’ve just mentioned, and more. The issues at stake include such trifles as who we are, and how we should see ourselves, and how the universe ticks.

I hope you enjoy this issue of Philosophy Now, which is eight pages longer than usual. Remember, this is the best time in history to stay safely indoors and read philosophy!

Dietmar Rabich (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/file:dülmen,_heilig-kreuz-kirche,_uhrwerk_--_2019_--_3056.jpg), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode