Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Street Philosopher

Floating Over Fallowfield

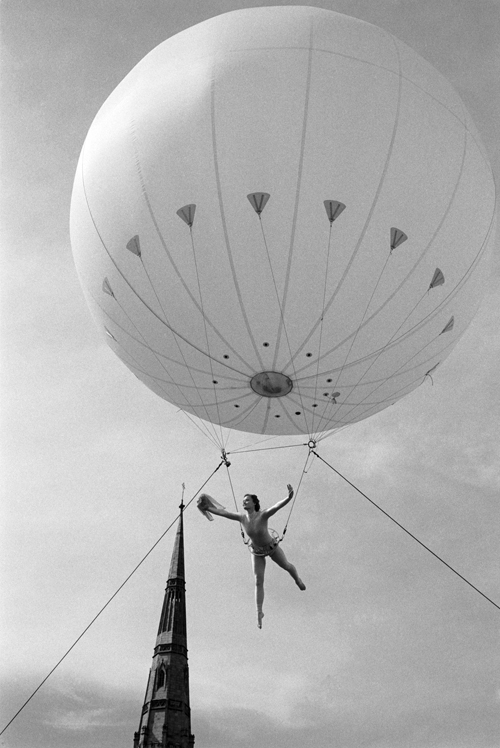

Seán Moran takes a bird’s-eye view of risk.

Well, would you? I like the idea in principle; but I’m sure that the cold reality of signing a legal disclaimer against death or injury and being strapped into a balloon harness would make me think again. Imagine the sense of freedom, though. We’ve been locked down for all this time, so the chance of escaping up – whatever that means in practice – is an attractive one.

For some of us, this upward flight is to the life of the mind. Louisa May Alcott, the American author of Little Women (1868) said: “My definition of a philosopher is of a man up in a balloon, with his family and friends holding the ropes which confine him to earth and trying to haul him down.” Her father, Amos Bronson Alcott, was a philosopher, and Louisa May’s mild rebuke likely refers to the financial worries he inflicted on his family whilst his head was metaphorically in the clouds.

Many of us took that vertical trajectory last year. Just before the first Covid lockdown, the BBC reported that “Book sales surge as readers seek escapism and education” (March 2020). Unfortunately bricks-and-mortar book retailers had to shut down, so the upward surge was not maintained. I personally indulged in book-buying sprees every time the bookshops and charity (thrift) shops re-opened; and I’m taking more risks with the kind of tomes I pick up.

Of course, ‘risk’ is a relative term: the minor perils of discovering that the novel or philosophy monograph you bought was a dud are not in the same league as the hazards of real physical adventure. But it is sometimes worth leaving our mental and physical comfort zones, for the sake of the unexpected pleasures that may come our way. John Gillespie Magee Jr, an Anglo-American World War 2 pilot, puts this beautifully in his poem ‘High Flight’ (1941):

“Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

Of sun-split clouds — and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence.”

Though he flew a Spitfire, his words work equally well for the aerial ballerina in my photograph. The poem’s last line is evocative: “Put out my hand, and touched the face of God” – or, in this case, seemed to touch the spire of Holy Trinity Church, Fallowfield, Manchester.

Magee’s poem was published posthumously. His parachute didn’t open in time after a mid-air collision. That’s an unfortunate downside of adventure: it poses threats to our safety. But it’s important to keep things in perspective and balance the risks against the potential benefits. When the world opens up to us again in a post-pandemic rebirth, we might – quite naturally – be unduly cautious. After a long stretch of restrictions, a world of new possibilities is on the horizon – what the Ancient Greek philosophers called a kairos, a time of opportunity.

To take advantage of it, we’ll need the virtue they named andreia – courage. Their paradigm example of courage was a brave warrior on the battlefield. The word andreia literally means ‘manly’. But in the Fourth Century BCE Socrates argued – somewhat controversially for the time – that women were just as courageous as men. Our sky dancer is probably braver than most of her audience, men and women.

‘Virtue’ also comes from a word for ‘man’, vir, but this time in Latin. Aristotle placed the virtue of courage between the extremes of foolhardiness and cowardice. Foolhardy persons rashly endanger their own lives from an excess of courage. We see this in horrifying internet clips of people posing for a selfie in high places who then fall to their deaths moments later. By any rational criteria, the prize of a ‘like’ was not worth their exposure to avoidable danger. At the other extreme, timid persons are deficient in courage and won’t accept any personal risk – even when it is worth it.

Photo © Seán Moran 2021

Calculating Risks

Our intuitive judgements of risk are notoriously unreliable. In The Philosophy of Risk by John Chicken and Tamar Posner (1998), we read that subjective estimations of risk “will have much larger margins of error associated with them than will judgements based soundly on hard, relevant, quantitative data.” It would not surprise me if a careful mathematical calculation showed that the van journey bringing the balloon crew to Manchester was riskier than the aerial performance itself. (And yes; an expert in risk aversion really is called John C. Chicken – a clear case of nominative determinism in action. Nominative determinism is the idea that people are drawn to lives that suit their names. If there’s a match, your name is an ‘aptronym’. It was first noticed in an article in the British Journal of Urology (1977, vol. 49, no.2) about incontinence – by A.J. Splatt and D. Weedon.)

Chicken and Posner’s proposition is that Risk = Hazard × Exposure. If you don’t go up in the balloon, your exposure is zero and there’s no risk from it. And if the equipment is 100% safe, the hazard is zero and there’s still no risk, however long you stay up. The hazard can never be zero, though. There’s always a small possibility that the cables could snap; that the balloon could be burst by the propellers of an illegally-flown drone; or that one of the ground crew holding the cables could sneeze at the precise moment that his other earth-bound colleague was being stung by a Mancunian wasp. Fortunately, none of those disastrous events happened, and we watched the athletic and artistic performance agog with delight.

As our aerial dancer surveyed the scene below, what would she have noticed? This was at the Manchester Mela – an annual celebration of South Asian culture – so she would have seen Pakistani dancers, Indian sari stalls, and a mahout riding a mechanical elephant; heard Bollywood bands and Punjabi drummers; and smell the aroma of the finest food west of the Khyber Pass. Culturally, her act had little in common with the milieu beneath her. (Never once during many trips to Pakistan and India did I spot a ballerina dangling from a balloon. I would have remembered.) Somehow it worked, though. Whoever took the risk of booking such an apparently incongruous act had made the right decision. Everything about the Mela was larger than life – spicier, bolder, louder, more vivid – and the balloon act fitted perfectly.

We might say that the booking agent used ‘cultural courage’ in mixing such seemingly incompatible modes of performance. This applied to the performers on terra firma too. A parade through the crowds at the Mela was led by an African dancer, and the Bollywood band behind him had Asian and Caucasian musicians playing side by side, sharing their enjoyment of this infectious music.

A more risky intermingling – but one we can all indulge in – involves the virtue of intellectual courage. American philosopher Linda Zagzebski explores this in her book Virtues of the Mind (1996), but we can trace the idea back to the Roman poet Horace (20 BCE) and his phrase Sapere aude – ‘Dare to think’ – which Immanuel Kant made the motto of the Eighteenth Century Enlightenment.

We live in a period in which many people are in ‘epistemic silos’, being fundamentally and unassailably opposed to the views of others who inhabit competing silos. If American politics, British Brexit, or people’s attitudes to Covid masks and vaccines spring to your mind, you’re a step ahead of me. These are not just matters of nuanced differences and subtle shades of meaning. Basic facts are in dispute. If we can’t even agree on straightforward actualities, how can we reach across the divide? But try we must, and this will take intellectual courage, perhaps even physical courage. This is not a time to adopt a postmodernist stance that allows for multiple perspectives on ‘reality’ and denies the legitimacy of any overall narrative. Arguably, that stance is what’s caused the silo problem in the first place – at least in part. No. Let’s ‘Restore Reason to her throne’, as Bertie Wooster says.

A standard challenge often made by conspiracy theorists is: “Do your own research!” It’s an invitation for us to float into the same web-based hall of mirrors vortex they inhabit. If we are intellectually brave, we could accept their well-meant invitation. The intellectual risk is that if we are foolhardy we might ourselves succumb to the disinformation. Plenty of otherwise intelligent people have done exactly that. But “It is the mark of an educated mind to entertain a thought without accepting it” (not Aristotle’s words, despite what you may have read on the internet). We need to step into the echo chamber armed with Scottish philosopher David Hume’s advice that, “A wise man… proportions his belief to the evidence” (An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, 1748). And when it comes to the more outlandish claims we will encounter, the ‘Sagan Standard’ (after Carl Sagan) should apply: ‘Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence’. The benefit of this intellectually risky enterprise is that you will be able to have conversations with folks in other silos.

Good luck; and may you return to the solid ground of reality with all your marbles intact!

Though not without some misgivings, I could temporarily swap places with the conspiracy theorists, even with the sky dancer. So could you. In preparation, we would have to familiarise ourselves with the equipment, keeping the balloon near the ground at first. Here there would be virtually zero risk: the worst that could happen would be an undignified fall of a few inches. Then we would begin to trust the balloon, the harness, and so on. We would also cultivate faith in the ground crew holding the cables that stopped us floating away. Gradually, we could practise our balletic routine at higher and higher altitudes – until one fine day we’re up in the skies over Manchester entertaining a crowd of thousands.

Volare aude – ‘Dare to soar’.

Now, would you?

© Dr Seán Moran 2021

Seán Moran teaches postgraduate students in Ireland, and is professor of philosophy at a university in the Punjab.