Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Letters

Letters

The Re-Presentation of Representation • Dazed & Confused by Art & Morality • Thinking About Words • Toil, Leisure & Idealism • Work of Art & Morality • Mortal Remains

The Re-Presentation of Representation

Dear Editor: I think The Big Art Issue (Issue 143) demonstrates why philosophy cannot get to grips with the arts. Artists use a range of media to represent both the disharmony and harmony of the world as presented to them in all its richness of pain, love, horror, beauty, madness and transcendence. It is always an attempt to re-present aspects of the world as presented in the artist’s lived experience. If successful, it will produce resonances of feeling between the artist and their audience. The problems occur when philosophers attempt to categorize and conceptualize works of art, because they are then representing the already-represented. This process of abstracting from an abstraction moves us even further away from the lived experience of the artist. In proof of this, I note that none of your contributors focused on the nature of the aesthetic experience itself, but used art to represent their own moral or other questions. Perhaps the message is that philosophers should allow art to speak for itself?

Steve Brewer, St Ives, Cornwall

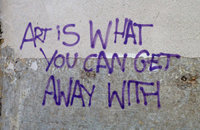

Dear Editor: Reading Issue 143, with its focus on art, I was reminded of this photo I took about ten years ago.

It was on the wall of a redundant factory in Leeds. I have no idea who had sprayed it, or, more intriguingly, their motivation. Was this an attempt at creating a work of art in its own right, or was this a cry of frustration after encountering something in Leeds’ art gallery? Perhaps it was a student who wanted to paint landscapes but who found themselves encouraged to make installations. Whatever the intention of the person who sprayed it, it does, in a dramatic way, raise the interesting question of where the boundary rests when claiming any object as a work of art.

David Morling, Beer, Devon

Dazed & Confused by Art & Morality

Dear Editor: I was rather dazed and confused after reading Jessica Logue’s article on ‘Art & Morality’ in PN 143. Unless you’re a fundamentalist, most moral issues are not black and white; they form a spectrum of shades of grey.

When art is of dubious value, taking the moral high road appears to be relatively easy. For example, I sort and prep vinyl records for sale in our charity shop or online. When the guilty verdict came in on the sex pest Rolf Harris, I immediately discarded the only two records by him we had for sale – no great loss artistically or financially. But does it make a difference if the artist is dead or alive? I have not discarded records by the late murderer Phil Spector, nor the long-dead anti-Semite Richard Wagner. Is anyone suggesting that we ban Wagner’s music from opera houses and burn his scores and recordings? That seems unlikely, as neither the man himself nor his estate benefits from his work. But it would be different if The Ring Cycle had been written by a living neo-Nazi.

So I conducted a thought experiment with friends and family: A charity receives a donation of a signed water-colour by Adolf Hitler. What to do – destroy it immediately, or send it to auction? Virtue ethics might dictate that the painting should be destroyed; but at auction it might fetch a fortune that would greatly benefit the charity. However, the PR damage of an auction could also be immense – plus, the painting might be bought by a neo-Nazi. This raises the utilitarian approach: how much money raised would be enough to conclude that such an auction promoted the greatest good? In my non-scientific sample, the consensus was to go to auction, the best-case scenario being that the winner buys it purely in order to destroy it. My own view is to buy it through crowdfunding, in order to stage a public bonfire.

With art of accepted value by a dead artist there is a middle way. In the early 70s I attended a production of Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta (c.1590). There’s an obnoxious anti-Semitic rant in it, and the director decided not to edit it out. Instead, at the key moment the action stopped, the actors walked off, then returned with the text, which they read deadpan at the front of the stage; then the action resumed. Although this broke the fourth wall (very unusual back then), as an audience member I found the experience very powerful.

We now live in a post-truth environment where the concept of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ has been discarded under the tyranny of ‘the offended’. For instance, although Woody Allen has never been found guilty in any court of any sexual offence, Logue has decided to abandon watching his movies. She implies that if Allen were to show remorse he would be easier to forgive. This is precisely the argument used by political tyrants, by the torturer O’Brien in 1984, and by ‘the offended’ of today.

At the denouement of Agatha Christie’s Murder on The Orient Express, Poirot suffers a profound moral and ethical crisis. [Spoiler ahead!] Virtue ethics would dictate that he should follow the letter of the law and send twelve people to the gallows; or he can follow natural justice and let them go free, to live with their guilt. What should he do?

Terry Hyde, Yelverton, Devon

Dear Editor: I write to articulate two criticisms of the points made in Jessica Logue’s article on ‘Art and Morality’ in Issue 143. Firstly, in response to Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994: while I recognise the line of argument that suicide derives from a sense of pain associated with personal disempowerment, I find her statement, ‘Suicide is often the result of a mental illness’ useless. Given that there is neither common consensus on what constitutes a mental illness, nor a definition posited by Logue, I judge that she might as well have said that ‘suicide is often caused by suicidal thoughts’. There needs to be far more rigorous attempts to define what constitutes mental illness and the extent to which it can absolve someone of personal responsibility – not that I condemn those who commit or attempt suicide as immoral.

Secondly, Logue bundles incest – specifically the incest of Lord Byron – together with adultery, rape, and racism as unquestionably immoral. But incest does not per se denote any kind of abuse: it simply means sexual contact between close relatives. In the case of Byron’s (unproven) incest, I can find no suggestion that he was abusive, and both parties were adults. Again, this requires far more rigorous collective self-assessment.

Adam Hitchcock, Reading, Berkshire

Dear Editor: Go climb a mountain, make love, write an email… someone else is involved. No human action stands on its own: it is always connected in some way with the rest of life. Everything we do, we do in context. When someone approves or disapproves, we are in the territory of ethics. You can’t keep art and morality apart. The question is, which has priority? The Japanese Samurai and European duellists choreographed killing itself as a work of art. Caravaggio, one of the greatest Italian painters, was a murderer. Benvenuto Cellini, supreme goldsmith and sculptor, was a thoroughly nasty character. Gesualdo, groundbreaking Renaissance composer, killed his wife and her lover. Suicide is not confined to pop singers. Think, for the twentieth century alone, of Mark Gertler, Dora Carrington, Mark Rothko, Virginia Woolf… From the internet I find that in the last two centuries about 2% of artists died by their own hand. (Poets and writers have a slightly higher suicide rate than the general population; painters and architects rather lower.) But why do we want to know if a painter or musician is wicked or not? Shall we shut our ears to the music of a dissolute pianist? Do we turn our back on Harlech Castle because it was built to oppress the locals? Is a Spitfire less admirable for being a killing machine? Take this a little further. Before we buy a product, must we first be satisfied that the designer not only treats their family well, but also pays their taxes and looks after their employees? Is this included in ethics? Or is ethics only interesting if it has to do with sex?

A work of art is supposed to contribute in some way to human good. But we are complicated, inconsistent beings. Can anyone tell us whether Phidias bribed the builders of the Parthenon, or Praxiteles flogged his slaves? Anonymous ancient works, medieval, classical, Chi nese, or whatever, display the evidence of their quality. But they tell us nothing of their authors’ score in the virtue stakes.

Private virtue is one thing. But if we are to turn our eyes from a painting of Venus or a sunset, stop our ears to a Requiem mass, because the artist was perhaps dishonest, how can it be okay to show thousands of murders and other horrors on television every week? Or is that all right, provided the camera crew don’t wolf-whistle at women?

Every work of art is a sample of a possible world of experience. One thing we can b e sure of: no possible world will be squeaky-clean. Good people and bad will go on making things. Some of what they make will be fine and beautiful, but not because they are honest, kind or politically correct. They only have to be good artists.

Tom Chamberlain, Newark-on-Trent

Thinking About Words

Dear Editor: In PN 143 Raymond Tallis marvels at our ability to think about thinking. But his over-emphasis on specifically linguistic thinking, claiming that “for most people, thought is overwhelmingly in words rather than images”, is typical of our over-literary culture. Where is the evidence for this commonly assumed sweeping generalisation? And how can we possibly gather data to support such a hypothesis when thought is essentially private? It may be correct that highly abstract thinking, like philosophising, is very symbol-dependent, especially word-dependent. But a huge chunk of thinking, for instance concerning quantitative relations, art, music, dance, spatial navigation, everyday locomotion, friendship, etc… is mostly non-verbal. Even in the lives of the literati, thinking often bypasses words altogether. Making a cup of tea, driving a car, playing a game, recalling events, require thought but not necessarily any mental use of words at all. Would your thoughts about a loved one change if they were nameless?

Language was a twentieth century obsession in philosophy. Logical positivists and others, including Wittgenstein, thought that most if not all philosophical problems were due to misunderstanding linguistic limitations. Structuralists thought linguistic theories were a model for philosophy, psychology, sociology and anthropology. Postmodernists regarded almost everything as a closed domain of inter-referential text. The very influential Sapir-Whorf hypothesis even suggested that language determines and limits what can be thought about at all.

It is clear that symbols, especially words, make mental connectedness and communication much simpler, facilitating easier concept and theory formation; but words per se are meaningless tokens which only become meaningful when labelling or linking to concepts and their affective associations. It is this deeper cognitive level of memorised constructs – highly processed but ultimately derived from traces of qualitative lived experience filtered and structured for our needs – which is the realm of thought. Thinking isn’t just a nexus of labels referring to other labels; the labels have to eventually touch base with non-verbal experience, to work at all. Even in an artificial intelligence system, the input can be words and the output can be words, but the intervening processing is not words. It is a fallacy to infer that just because people receive and report most of their thinking in words, that their thinking is mostly words.

Christopher Burke, Manchester

Toil, Leisure & Idealism

Dear Editor: In PN Issue 142, Jacob Snyder’s article ‘Anxious Idleness’ discusses the disappointment that when you finally achieve leisure it turns out to be a rather boring dead-end. He describes how Aristotle and Locke tackled this paradox. Aristotle said work, recreation, and leisure were three different things, leisure being the most exalted because it has no external purpose. Recreation, said Aristotle, is different because it’s merely a rest from work to sharpen you up for later work. Locke, on the other hand, merged recreation with leisure. He points out that the rich and famous are just as likely as the working classes to spend their spare time at ‘cards, dice, and drink’, and so concluded that there ought to be a use for our recreation. This involves ‘the use of enjoyable practical reason’. But doesn’t that make recreation a lot like work?

I suggest we can solve the paradox of leisure by starting from a social rather than an individual angle. Human beings are powerfully motivated by the social groups we belong to. These groups are the interlocking building-blocks that make up society: the families, clubs, gangs, businesses, tribes, nations, and multinational corporations. A person usually belongs to several groups. But the motivating element will always be peer recognition, which is to say, being liked, trusted, admired, or regarded as valuable within the group. Soldiers regularly risk their lives for their colleagues: medals are an after-thought. Aristotle’s ‘exalted leisure’ and Locke’s ‘practical reason’ seem unreliable motivators, whereas simple peer recognition motivates us all, from the toddler to the elderly. This group perspective suggests that the desire to be recognised for useful work is a considerably more powerful motivator than the seductive promise of leisure.

This society-based thinking is the subject of my book, The Wheels of Society, in which I argue that corporate greed seems to drive all our dangerous behaviour; pollution, habitat destruction, and over-consumption of the Earth’s resources. If corporate greed is the root cause of these worries, maybe we should change our view of society. Rather than seeing ourselves as a population of statistically modelled self-seeking individuals, we should notice the primacy of our (greedy) cooperating groups. They are so obvious that we routinely ignore them.

A.C.B. Wilson, Bradford on Avon

Dear Editor: In ‘Anxious Idleness’ in Issue 142, Jacob Snyder raises an interesting question about “the moral guilt we feel when we are idle” (not felt equally by all!). The issue of guilt seems to point beyond philosophy to the realms of psychology and the spirit. On the psychological side: when I was growing up, my parents would occasionally accuse me of laziness, which made me feel bad. I have internalized this guilt to some extent, and it rears its head whenever I’m not busy doing something that someone else thinks is important. On the spiritual side: the ancient myth of a Golden Age depicts human life as originally one of pleasure, and freedom from labor. Such is the condition of Adam and Eve before their fall from grace, when God curses Adam with a life of toil. Our idea of postmortem bliss is similarly one of leisure. This suggests that we see labor as, at best, a necessary evil we must endure. But at the same time, sloth is counted among the Seven Deadly Sins, implying that industriousness is a virtue. So our spiritual authorities appear to be ambivalent about labor.

I think the real source of guilt over inactivity is the press of time. We have a sense that we’re born for a purpose, perhaps even with a mission, and have a limited time in which to carry it out. After all, have we been endowed with our faculties and talents just to lie on a beach getting drunk – or worse, to play golf?

Paul Vitols, North Vancouver

Dear Editor: I was intrigued with the article by Jacob Snyder about leisure. Snyder contrasts the teaching of Aristotle that leisure, especially philosophical contemplation, is the ultimate goal of human life, with the claim of John Locke that even what we usually regard as leisure time should be spent in some kind of work or activity. In a sense the question here is what the highest or ideal purpose of a person should be. This question has been debated for centuries in the Christian tradition. Two theories about this are similar to the opinions of Aristotle and Locke. One (reflecting Plato’s idea of purpose), is that the highest ideal of humanity is the eternal contemplation of God. The second theory proposes the Aristotle-like idea that our ultimate destiny is to become the active, creative people God always intended us to be. This destiny would best be fulfilled in a new physical creation. Both these theories have substantial support from the Bible and among contemporary theologians. A believer’s opinion about this affects not only her hope for the afterlife but also how she seeks to develop her life in the present world.

Daniel Boerman, Hudsonville, Michigan

Dear Editor: Mr Kerry (Letters, 143) challenges my view that gay committed Christians should not act out on their sexual orientation by saying that this prohibition violates something intrinsic to their relational nature. Thus, such a restriction would be wrong. But the biblical doctrine of the Fall claims that all humans are out of joint in one way or another because of the effects of original sin. For the gay Christian, the self-denial that Christ enjoins on all his followers (Luke 9:23-26) involves an erotic inhibition; but a heterosexual Christian also must deny any of their loves that are outside of the will of God. The cross of self-denial has the same weight for every Christian, although it does not have the same shape.

Douglas Groothuis, Denver

Work of Art & Morality

Dear Editor: I enjoyed the magazine’s foray into literary nonfiction in ‘Robot Rules’ in Issue 139. Brett Wilson frames his essay with the tale of ‘your’ cat Tybalt molested by an automated lawnmower, on whose behalf you go to law. There eventually you reach forward, press a button, and see the robotic lawyer collapse before your eyes. Your encounter with a robot lawyer is about as unsatisfactory as your cat’s encounter with a robot lawnmower.

The frame is written in folksy skaz style (colloquialisms, regionalisms, puns, litotes, grandiloquence on occasion) but the best part lies in the literary allusions. We have Tybalt’s bloodline, which runs through a graphic novel The Prince of Cats, Romeo and Juliet, the medieval Reynard the Fox cycle, and, unless I am thinking too hard, the nursery rhyme ‘Hey Diddle Diddle, the Cat and the Fiddle’. There is an allusion to Hamlet and the jury of peers may be an allusion to the Parliament of Fowls where we find the adage, “choosing not to act is still a choice.” The other side of the coin from the literary, the nonfiction argumentation – the meat in the sandwich – must be impeccable. Martin Jenkins in Issue 140 suggests that Brett Wilson should get a better lawyer, since the answer he seeks already exists in the common law. This is correct, but the legal points are a sideshow to the philosophy, where Wilson’s points and arguments are sound.

Judith Alexander, Calgary

Mortal Remains

I would rather be a fossil

When I am no longer living,

For thus, I could maintain my form

Though my soul would be missing.

Boghos Artinian, Beirut