Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

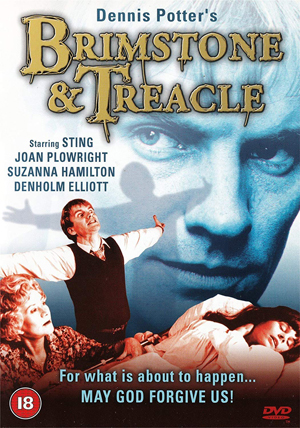

Brimstone and Treacle

Thomas R. Morgan notes a diabolical, and angelic, case of anti-realism.

Having always been intrigued by this controversial tale by the British playwright Dennis Potter, it’s interesting to me to notice how my appreciation of its meanings has altered since I first watched the film in 1982.

Changing interpretations is a phenomenon common to all forms of art. With maturity, new levels of meaning are discovered within what initially appeared straightforward – even if the artists weren’t conscious of those meanings during the act of creating it! There is danger of course, in imposing meanings that aren’t really intended, but I have come to believe that in the case of Brimstone and Treacle, layers of meaning are available in a full appreciation of its plot. For many years, the media’s fixation with the sexual abuse elements in the story, and subsequent censorship, contributed to an overshadowing of the tale’s more subtle and intriguing philosophical and religious aspects, some of which I want to explore here. Although Brimstone and Treacle can be most obviously analysed in terms of its moral messages and ethical implications, here I want to focus on its treatment of reality itself.

Film Images © MGM 1982

The film was converted into two dramatic versions for the screen; one a TV drama, the other a movie. Here I will concentrate on the film version directed by Richard Locraine, which is far more ambiguous, and thus more suitable to illustrate my observations, than its original 1976 TV counterpart, where the antagonist is unequivocally mischievous and demonic.

Written by Potter apparently during a period of intense anguish and moral cynicism, bordering on what sounds like a nervous breakdown, Brimstone and Treacle has a simple plot, with minimal characters and locations. A family consisting of a middle-aged couple, Tom (in the film played by Denholm Elliot, reprising his role from 1976) and Norma Bates (Joan Plowright), and their profoundly disabled daughter Patti (Suzanna Hamilton), has its inner dynamics challenged when a stranger, calling himself Martin, infiltrates the already tense environment on the pretence of returning Tom’s wallet.

Martin (played by Sting), first intentionally bumps into Tom in London. After an awkward conversation where Martin attempts to convince Tom that he is an old family acquaintance, Martin feigns lightheadedness, collapsing in the street. Tom uses the diversion to give the strange young man the slip. Subsequently, Martin is seen to be in possession of Tom’s wallet (even here there is ambiguity as to whether Martin stole or found the wallet), which contains personal details, allowing Martin to trace Tom to his ‘cosy’ family home.

As I said, in the televised version the character of Martin is portrayed as explicitly demonic. The drama even opens with this quotation from Kierkegaard: “there resides infinitely more good in the demonic than in the trivial man.” However, Martin’s nature is explored much more subtly in the film. This is pertinent especially when we come to understand more about the character of Tom Bates. It is clear that Tom’s cynical attitude and adulterous tendencies – revealed through flashbacks to a sexual liaison with his secretary – and his appeals to such afflictions as ‘human disappointment’, make him equally if not more detestable than the sneering and mealy-mouthed Martin. This in turn challenges assumptions about the primary source of evil being located outside of human beings themselves.

Schizophrenic Reality

One philosophical perspective which resonates with this note of caution, and which can be adopted to analyse the film, is anti-realism. The term was coined by the British philosopher Michael Dummett in 1982, only coincidentally the same year that the film was released. There are many branches of anti-realism, including scientific, linguistic, and metaphysical versions; but they all share the notion that reality is not simply an objective phenomenon. Anti-realism nevertheless allows an overriding reality which underpins other, contrasting subjective realities. (It’s not to be confused with Nelson Goodman’s ‘irrealism’, in which different subjective realities do not share a larger common reality.)

The philosopher Ray Holland illustrated anti-realism effectively in his ‘child on a railway crossing’ example. If one were to witness a boy narrowly escaping serious injury or death on a railway crossing as a train brakes just in time to avoid hitting him, one could interpret the event in more than one way. It could just be a case of luck, wherein the prevailing conditions just happened to work in the boy’s favour. On the other hand, one could attach greater significance to the event, perhaps perceiving a divine or miraculous influence in the outcome. Holland’s point is that, although factual claims are being made about the event, the truth cannot be known as objective fact, and therefore the reality of what happened necessarily takes on a subjective aspect. In other words, it is just as true to say that what happened was miraculous as to say it was a coincidence: both takes on reality are equally valid, neither having been disproved. Anti-realism in this sense is therefore the idea that contrasting perspectives can be simultaneously equally valid or real.

A related idea was suggested by Ludwig Wittgenstein in his Philosophical Investigations (1953), in which he explored the relationship between reality and language. As opposed to ‘picturing’ reality – as he originally considered in his earlier Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) – here language derives meaning through its use: through the context and its application. Wittgenstein here wrote that “the limits of my language means the limits of my world.” This implies, for example, that an atheist experiences a different version of reality to a theist by virtue of the language they use to describe it – as God-created or uncreated, for example. But for an anti-realist the absence of objective criteria renders all viable interpretations real. Therefore, on this view, God is both real and not real. And as long as the respective uses of language are misinterpreted by the other side, the two realities will remain polarised.

Such a polarised dynamic is at play in Brimstone and Treacle. Two realities (at least) are superimposed upon the events as they unfold – so much so that the characters could be said to occupy different worlds. The contrast between these realities is central to the drama.

Tom Bates is immediately suspicious of the interloper Martin. He views him as (apparently) unemployed, scheming and as a potential danger to Patti. Norma, by contrast, is swiftly taken in by Martin’s charms, welcoming the stranger into the family home, essentially as an antidote to the dull, unappreciated limbo of her daily routine. Her reference to ‘this little box’ not being ‘all there is’, in relation to the limits of her world, hints at realities beyond the ones immediately perceived, as well as Martin’s short-lived but seemingly positive impact on her life.

However, it is not only through Martin that the distinct realities of Norma and Tom are realised. The couple’s distinct attitudes towards their daughter Patti and her condition serve to highlight further how a single state of affairs can contain multiple yet equally real interpretations. Tom exhibits little hope regarding Patti’s future, with exclamations like ‘there are no miracles’ and ‘she’s gone from us’. It could be said that Tom occupies a kind of hell in his certainty that his bitter and cynical reality is absolute; whereas Norma’s take on reality is hopeful, bordering on the mystical – claiming for example that there is ‘a light, a definite light’ in Patti’s expression. These dual realities are extended in their own mutually exclusive directions with the arrival of Martin, who is a damning devil to Tom, and a saving angel to Norma.

In the film version of Brimstone and Treacle, Sting’s Martin is never explicitly revealed to be angel or devil; rather, he is both. Although he commits atrocious acts, their true meaning and essence are left hidden. His rape of Patti goes unseen by both Tom and Norma. You might imagine that if she had known, this would have realigned Norma’s reality with Tom’s, but it’s not so simple. Interestingly (and disturbingly), when Patti recovers her mental faculties in the final moments of the film – as a result of the abuse by Martin, it is implied – her first lucid accusation is not against her abuser. It is against her father for his adultery, of which she has seen evidence, just before the traffic accident which led to her condition. Like Norma and Tom, the viewer must consult their own reality to decide what Martin is and means. We are left with a single individual who could be good or bad, depending on the reality one occupies.

© Thomas R. Morgan 2021

Thomas R. Morgan is teacher of religious studies, philosophy, and ethics at Westcliff High, UK.