Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism by Kristen R. Ghodsee

Amber Edwards surveys the position of women under socialism.

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism is a short and snappy discussion of how the quality of women’s lives could be improved if society were rebuilt on some of the principles underpinning state socialism. Kristen Ghodsee, Professor of Russian and East European Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, argues that unregulated capitalism is bad for women, and that by learning from the history of socialism we can create a more egalitarian path to our collective future. To make her argument she explores the socialisation of women in the workplace, considers childbearing from a social and economic viewpoint, and discusses women in leadership, women as citizens, and, in reference to the title, women’s sexuality.

She begins by examining sexuality in popular culture, highlighting that when we turn on the TV or open a magazine we are often immediately presented with sexualised images. This demonstrates capitalism’s tendency to commodify sexuality, women’s bodies, and basic human emotions, thus normalising this behavior and helping to create unequal conditions for women. Ghodsee presents a series of arguments to show how this commodification could be reduced by applying some key socialist ideas. She references case studies from former Eastern European socialist states such as Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania, the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. She then argues that under capitalism the economic independence of women is insecure, and that in the absence of security the freedom to make personal choices is eroded. This is further complicated by the fact that women tend to earn less than men do, encouraging the patriarchal notion that women are best placed within the domestic sphere. This can trap women in undesirable relationships and create toxic power dynamics within the family, and affords women specifically very little freedom to leave, with no source of income independent of their spouse, and no means to maintain the skill set required to find work within the modern economy. Women are then indebted to their men, and expected to repay them in sexual and/or household and childrearing activities which go completely unrecognised by the market.

These pressures can render a woman worthless in a capitalist society as anything other than a source of future labourers. Ghodsee argues that this was not the case in at least some socialist states such as East Germany, Hungary, and Poland, where intimate relationships were free from economic dependence because women had their own sources of income and access to social welfare, thus eliminating the necessity of marrying for money or social support.

The book sets out to show that capitalism’s harms are universal and have a profound effect on women. Ghodsee does advocate a socialist society, but doesn’t naïvely imagine socialist states as perfect utopias. She acknowledges that no Eastern Bloc state ever achieved full gender equality (p.8), highlighting that gender pay gaps still existed and that women’s entry into the workforce was not always to the benefit of them personally, but in the interests of the state, or for the ‘collective good’ (p.10). Nevertheless, state socialism provided educational opportunities for women and entry into the workplace, allowing them to develop their own skill sets. The availability of state support also meant that financial pressures on women generally eased.

Ghodsee addresses popular criticisms of what used to be called ‘actually existing socialism’: an inefficient economic system; bread lines; curtain-twitching neighbours divulging information to the secret police; at worst, terrifying repression and Stalin’s famines. She acknowledges that there were certainly failures in past socialist experiments, but claims there were also extraordinary successes, which are worth salvaging in challenging capitalism. Here she quotes Spinoza, “If you want the future to be different from the past, study the past” (p.23). This is the only mention of a traditional philosopher in the entire book. There are however numerous references to early 20th century Marxist social and feminist theorists, such as Clara Zetkin and August Bebel, who were revered in post-war Eastern Europe. This, in my opinion, is one of the strengths of the book, as it opens up a refreshing and innovative approach to feminism typically omitted from accounts today. The book is also scattered with biographies of feminists, which humanizes the more abstract ideas in personal ways.

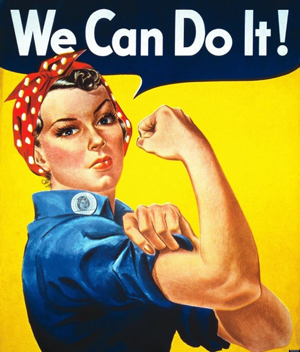

Rosie the Riveter

There are two chapters exploring sex, focusing specifically on sexual economics and the normalisation of sex under socialism in comparison to the West’s puritanical hangups. Ghodsee presents studies showing that women in the German Democratic Republic experienced higher levels of sexual satisfaction compared to those in West Germany. This is attributed to a number of factors, such as relationships being based on love and mutual need instead of an idea of them as commodities for consumption; people retreating to the private sphere to avoid state interference; and generally, people having more time for sex, with fewer commercial distractions. Sex was also encouraged by a state eager to distract from economic deprivation and travel restrictions.

Ghodsee shows that the introduction of socialist ideals within contemporary Western capitalist systems could be beneficial to women. She advocates a Universal Basic Income to compensate for women’s unpaid household labours, as well as an expansion of public services. She also advocates the introduction of job guarantees, which would be beneficial for anyone who might face future job cuts due to the rise of artificial intelligence. Ghodsee shows how cuts to public services have had significant negative effects on women’s mental health, using a prominent example of a cut to a publicly-funded women-only counselling service which forced women into mixed counselling sessions – spaces where they might not feel comfortable discussing their concerns. Her book also addresses the necessity of creating female role models, highlighting the success of state-mandated quotas for women to fulfil leadership positions. Ghodsee also acknowledges that quota-filling can lead to companies ticking boxes rather than reshaping societal attitudes and counteracting unconscious gender stereotypes, and addresses the concern that such quotas can exclude non-white and/or non-middle-class women.

The book has various elements of intersectionality. Intersectionality is the study of how the different facets of a person’s identity – such as gender, religion, race or social class – interact to affect their position in society. Indeed, the nature of the book’s subject matter requires recognition of the impact social class has on women’s opportunities. Ghodsee states that female emancipation was fundamental to the socialist vision from its inception, although class identity was always privileged over gender identity. She doesn’t think that women cannot succeed under capitalism, or take up leadership positions (Margaret Thatcher and Angela Merkel are examples). Rather, she argues that they have to do so under a model which is fundamentally against their progress because capitalism is based on ideals of meritocracy and the survival of the fittest in which both ‘merit’ and ‘fittest’ have gendered interpretations. There is an acknowledgement of the impact race has on the advancement of women’s progress under capitalism, too; and mention of how power hierarchies afford some women more privilege than others. However, the brevity with which this is covered is quite surprising, being confined to a couple of pages. It is also noticeable that of the eleven photos of feminists in the book, all bar Angela Davis are white. Furthermore, the only (extremely vague) reference to trans women is a mention of the Eastern Bloc failing to be concerned with gender nonconformity (p.9). A questionable use of the phrase ‘pretty woman’ in which the adjective adds no value to the meaning of the sentence, highlights the author’s lack of a critique of beauty ideals or the manner in which they are constructed under capitalism, or any radical alternatives that socialism might offer on female body image. The lack of intersectionality on matters of race and gender identity is quite disappointing, and frankly, surprising in a feminist book written in the present climate.

Otherwise I enjoyed this book, particularly Professor Ghodsee’s writing style. The text has a witty, dry tone, making it an accessible text, particularly as an introduction to feminism, capitalism, and socialism. The author includes personal anecdotes, lending context to the reality of sexism in capitalist societies. So I would recommend Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism to the general readership of Philosophy Now. However, I would not describe it as a traditional philosophical text, but rather as an introductory book on feminism. For (vastly) more in-depth and intersectional approaches to feminism, Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race, or Helen Hester’s Xenofeminism, would provide better philosophical overviews.

© Amber Edwards 2021

Amber Edwards is a librarian currently living in quarantine Rome.

• Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism, Kristen R. Ghodsee, 2018, Vintage, £9.99 pb, 240 pages, ISBN: 978-1529110579