Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Love & Romance

Iris Murdoch & The Mystery of Love

Stephen Leach looks with Murdoch at the three graces of love, art, and morality.

The English philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch (1919-1999) believed that although we may never fully know reality itself, love may help us glimpse something of it, since love alerts us to reality as it exists independently of our egos. How it does so is a mystery, but we seem to recognise that it does.

Murdoch set out her view of love in a number of essays on art and morals published between 1959 and 1969, which were subsequently republished, along with others, in the compilation Existentialists and Mystics (1997). I shall try to summarise her view and, in the final section, discuss three criticisms.

Something Other than Oneself is Real

Whereas Plato believed that art distracts us from reality, Murdoch argues in The Sublime and the Good (1959) that, on the contrary, art, by virtue of love, alerts us to what is real:

“Art and morals are, with certain provisos… one. Their essence is the same. The essence of both of them is love. Love is the perception of individuals. Love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real. Love and so art and morals, is the discovery of reality. What stuns us into a realisation of our supersensible destiny [ie, our mortality] is not, as Kant imagined, the formlessness of nature, but rather its unutterable particularity; and the most particular and individual of all things is the mind of man”

(p.215. All page numbers are from Existentialists and Mystics).

Murdoch claims that art, morals, and love share the same enemies: social convention and neurosis (by ‘neurosis’ she means, I think, self-obsession). In the first case our view of reality is obscured by the influence of predominant social mores; in the second, reality is obscured by our attempts to assimilate the ‘other’ into an egotistical fantasy world. We make these mistakes in our social lives, but they can also be seen recurring throughout the history of art – think of artists before and after they’ve reached their peak. But although the essence of art is love, that is not to say that art explicitly tells us to love:

“It is of course a fact that if art is love then art improves us morally, but this is, as it were accidental. The level at which that love works which is art is deeper than the level at which we deliberate concerning improvement. And indeed it is of the nature of love to be something deeper than our conscious and more simply social morality, and to be sometimes destructive of it. That is why all dictators, and would-be dictators… have mistrusted art” (p.218).

‘Art’ is here used to specifically mean good art. She would agree that dictators often have a liking for bad art.

As to the relationship between art and morals: well, the artist “is more like God than the moral agent” (p.219). This is not to say that Murdoch believed in God: she did not. She means rather that the artist, godlike, shows us a small part of reality beyond our egos. The best art does this so convincingly that, when we are shown what exists outside of our egotistical concerns, we are momentarily knocked off balance. By contrast, “the love which is not art inhabits the world of practice, the world which is haunted by incompleteness and lack of form, which is abhorred by art, and where action cannot always be accompanied by radiant understanding, or by significant and consoling emotions” (p.220). The world of practice is so messy that it can never be fully conveyed in any work of art. However, love is a feature of both.

The Temptation of Love and its Peril

In her essay ‘The Sublime and the Beautiful Revisited’ (1959), Murdoch situates herself in relation to Kant’s aesthetics. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) believed that we experience the sublime (as distinct from the beautiful) when we gain an awe-filled and sometimes frightening awareness of the world as existing outside of our own interests. Kant’s example was a walker high in the Alps experiencing, in the form of the sublime, a mixture of terror and delight, but also, as he becomes more aware of his own isolated but powerful rationality, a defiant pride. In Murdoch’s alternative, her spectator observes other people. For, she argues, when we become aware of the world as it exists outside our own interests, it is especially the particular that we notice. Her spectator, observing other people, experiences “that undramatic, because un-self-centred, agnosticism which goes with tolerance. To understand other people is a task which does not come to an end” (p.283).

Iris Murdoch © Simon Ellinas 2022 Please visit www.caricatures.org.uk

Murdoch argues that this humble respect for the autonomy of others is fundamental both to artistic creation and to morals. We are probably more used to the idea as bearing on morals. In art we are more familiar with the idea that writers and painters must empathise with their characters. Murdoch does not dispute the need for empathy, but (no doubt thinking of her own experience as a novelist) she thinks that it is nonetheless important for fictional characters to be regarded from afar – to be left free, so to speak, to make their own mistakes, as they stumblingly attempt to apprehend each other’s realities. She again makes the point that when we fail to respect the autonomy of another individual in both art and life, it is because we have been waylaid by convention or self-obsession. Either way, there can too easily be stereotyping or a too-quick summing up: “Form is the temptation of love and its peril… to round off a situation, to sum up a character. But the difference is that art has got to have form, whereas life need not” (p.285).

Be Ye Therefore Perfect

In ‘The Idea of Perfection’ (1962), Murdoch notes that in moral philosophy we tend to forget “the fact that an unexamined life can be virtuous and the fact that love is a central concept in morals” (p.299). We should remember that the moral world is at its foundation concerned with understanding other people, and, as such, love is at its core, for ‘Love is knowledge of the individual’.

However, we can never claim to fully understand another person. Hence she interprets Jesus’s admonition, “Be ye therefore perfect” (Matthew 5:48) as advice that we should pay more careful attention to that which is individual, particular and contingent, even though perfect understanding is impossible.

In moral philosophy she generally wishes to shift the emphasis from action to attention: “to express the idea of a just and loving gaze directed upon an individual reality. I believe this to be the characteristic and proper mark of the active moral agent” (p.327). For moral life is “not something that is switched off in between explicit moral choices” (p.329). She does not deny the importance of philosophical reflection, nor does she deny the importance of taking the correct moral action, but she argues that the nature of Goodness is misconceived when moral philosophy neglects the patient eye of love.

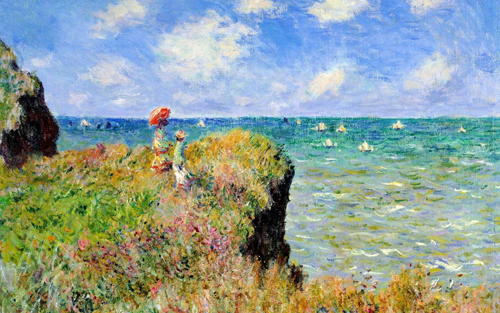

Claude Monet The Cliff Walk at Pourville 1882

The Reflection of the Warmth and Light of the Sun

She says more about the patient eye of love in ‘The Sovereignty of Good over other Concepts’ (1967):

“It is so patently a good thing to take delight in flowers and animals that people who bring home potted plants and watch kestrels might even be surprised at the notion that these things have anything to do with virtue” (p.370).

She observes that there are countless small pointers towards the Good that can be seen whenever we manage to momentarily put aside our selfish egos, but the Good itself remains mysteriously indefinable. Philosophers have tried to relate the Good to freedom, reason, happiness, courage, and history… however, “They seem to represent in each case the philosopher’s admiration for some specialised aspect of human conduct which is much less than the whole of excellence and sometimes dubious in itself” (p.384). And as for the relationship between Goodness and Love:

“Of course Good is sovereign over Love, as it is sovereign over other concepts, because Love can name something bad. But is there not nevertheless something about the conception of a refined love which is practically identical with goodness? Will not ‘Act lovingly’ translate ‘Act perfectly’, whereas ‘Act rationally’ will not? It is tempting to say so” (p.384).

She’s saying that we can love that which is bad, so love cannot always be relied upon, but nonetheless we seem to recognise that its natural inclination is towards the Good:

“Love is the general name of the quality of attachment and it is capable of infinite degradation and is the source of our greatest errors; but when it is even partially refined it is the energy and passion of the soul in its search for Good, the force that joins us to Good and joins us to the world through Good. Its existence is the unmistakable sign that we are spiritual creatures, attracted by excellence and made for the Good. It is a reflection of the warmth and light of the sun” (p.384).

Taking a Chance on Love

In her paper ‘On ‘God’ and ‘Good’’ (1969), Murdoch asks ‘‘How can we make ourselves morally better?’ Her answer is that we must first realise that “the enemy is the fat relentless ego” (p.342). This enemy is overlooked or underestimated when our focus is solely upon action. Instead, “We need a philosophy in which the concept of love, so rarely mentioned now by philosophers, can once again be made central” (p.337). We should also pay heed to psychology, for psychology exposes the power of the ego. Furthermore, we should remember that religion has designed a special technique to re-orientate the ego’s usual focus – prayer:

“Prayer is properly not petition, but simply an attention to God which is a form of love. With it goes the idea of grace, of a supernatural assistance to human endeavour which overcomes empirical limitations of personality. What is this attention like, and can those who are not religious believers still conceive of profiting by such an activity?” (p.344).

Non-believers can benefit from this technique. Indeed, they may already be more familiar with it than they realise:

“Consider being in love. Consider too the attempt to check being in love, and the need in such a case of another object to attend to. Where strong emotions of sexual love, or of hatred, resentment, or jealousy are concerned, ‘pure will’ can usually achieve little. It is small use telling oneself ‘Stop being in love, stop feeling resentment, be just.’ What is needed is a reorientation which will provide an energy of a different kind, from a different source… Deliberately falling out of love is not a jump of the will, it is the acquiring of new objects of attention and thus of new energies as a result of refocusing” (p.345).

For Murdoch, our appreciation of the world, like our appreciation of the Good, is a spiritual exercise – not in the sense of being other-worldly, but in the sense of overcoming the ego, so that we realise that the world exists regardless of our perception of it. “The idea of a really good man living in a private dream world seems unacceptable” (p.347).

She observes that in both morals and art our vision and achievements are inevitably imperfect, but what we strive for, and what we recognise to be real, is not:

“The idea of perfection moves, and possibly changes, us (as artist, worker, agent) because it inspires love in the part of us that is most worthy. One cannot feel unmixed love for a mediocre moral standard any more than one can for the work of a mediocre artist” (p.350).

When we love, we put aside the habitual activities of the ego in order to look at reality: “In the case of art and nature, such attention is immediately rewarded by the enjoyment of beauty. In the case of morality, although there are sometimes rewards, the idea of a reward is out of place” (p.354). But in both cases, “the real is the proper object of love” (p.355). However, unfortunately, only rarely do we overcome the possessive ego:

“human love is normally too profoundly possessive and also too ‘mechanical’ to be a place of vision. There is a paradox here about the nature of love itself. That the highest love is in some sense impersonal is something which we can indeed see in art, but which I think we cannot see clearly, except in a very piecemeal manner, in the relationships of human beings” (p.361).

Note, however, that she does admit that, in a piecemeal way, an unpossessive love can sometimes be found in human relationships – perhaps, for example, in the love of a parent for a child.

How then can we know that love has set us on the right track? I think Murdoch would say that to some extent we can rely on experience, but that, ultimately, we have to take a chance. As the film director D.A. Pennebaker once said, “It’s like playing blackjack in Vegas – you assume you’ll be lucky or you wouldn’t do it at all.” He was talking about directing films, but perhaps the same applies to our search for love.

Three Brief Criticisms

The Heart in the City Clinton van Inman 2022

Painting © Clinton Inman 2022 Facebook at Clinton.inman

Murdoch’s visions of love and art may be attractive, but are they trustworthy? Do they lead us through gates of ivory, or through gates of polished horn?

She criticises Jean-Paul Sartre’s focus on being loved as opposed to loving, but perhaps she falls into the opposite trap, since her emphasis is almost exclusively on loving as opposed to being loved. Such an exclusive focus may lead to a view of love as constant striving. Fortunately, one aspect of being loved can be acceptance of one’s imperfections. In a truly loving relationship, we are assured that sometimes it is acceptable to be imperfect. However, although Murdoch’s emphasis on loving as opposed to being loved is an oversight, this does not undermine her claims about love.

A second criticism is that the relationship between attention and action is unclear. Is careful attention to someone or something merely a necessary condition for good action, or something more? This is not a question to which I have an answer. I don’t believe that Murdoch claimed to have finally settled this problem either. Nonetheless, her point that there is more to moral life than making decisions seems to stand.

There is a third criticism that potentially reaches deeper. Iris Murdoch writes with love about love, so there is no problem with her being self-refuting here. But it might be objected that her claims have no firm philosophical foundations, and that therefore she offers us only visions of love.

To reply on her behalf: I would argue that she is well qualified to discuss love just because she does not discuss it from any pre-established philosophical foundation! Remember she says that “Love is the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real.” Most people, including Plato, do not find this to be a difficult realisation. But Murdoch did. She is suggesting that philosophical reflection alone may not be able to establish that something other than oneself is real. It may be for this very reason that she is well placed to take a fresh look at love.

© Dr Stephen Leach 2022

Stephen Leach is senior honorary fellow in philosophy at Keele University and coeditor, with James Tartaglia, of The Meaning of Life and the Great Philosophers (Routledge, 2018).