Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

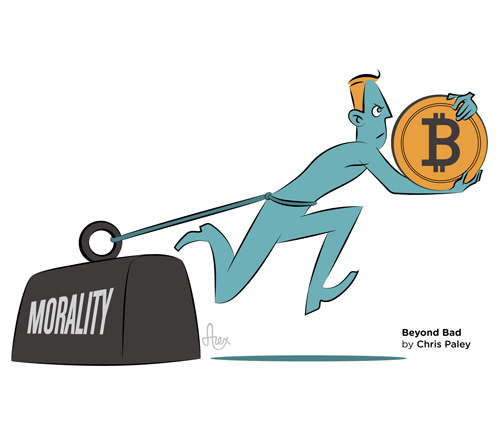

Beyond Bad by Chris Paley

Chris Paley wants us to leave morality behind completely.

“Morals are for suckers”, whereas “amorality will lead you to worldly success” says Chris Paley, who has a Cambridge doctorate in evolutionary biology and was briefly an investment banker. He cites an experiment in which the majority of drivers who refused to stop for pedestrians at a crossing in California were driving expensive cars. It is through such experiments, apparently, that ‘science’ has enabled us, in the last few decades, to understand what moral philosophers have been trying to explain for the last three millennia – why and how we moralise. Apparently, after reading Beyond Bad (2021) we will be able to junk not only moral philosophy, but morality itself.

“I’ll argue” announces Paley on p.2, “that humans have the mental machinery to moralise because it was in our ancestors’ genes’ interests.” However, since it is axiomatic in evolutionary psychology that any human behaviour is the product of genetic advantage, this is hardly an argument. Nevertheless, Paley takes the standard line: moral behaviour, he says, is allied to our species’ unique capacity for conflict-management and cooperation (what Jonathan Haidt dubs ‘groupishness’); and altruism/morality is ‘an optical illusion of the mind’, or deferred gratification for genes. He adds a pinch of Nietzsche in diagnosing that moralism arose from pleasure in vengeance, but views moral approval or disapproval mainly as outgrowths of a tribesman’s need to signal allegiance. To seem, rather than be, morally good, was from the outset the essential thing, says Paley. But although in the modern world we still ‘click into moral gear’, in fact morality has become redundant: “Today, we trade with people we’ll never see again” so our reputations are not at risk.

Really? Isn’t he aware of social media echoing round the global village; of the exacerbated moralism of cancel culture; of people being sacked and denounced when their long-ago youthful tweets are resurrected, dusted off, and touted around? Paley is at least original in bucking the moralistic trend, but he’s out of sync with reality.

Of course he is right that moral behaviour is riddled with sanctimony, self-righteousness and hypocrisy – but why invoke scientific experiments to ‘prove’ what has been immemorially acknowledged and analysed? His claim that morality should be jettisoned is more novel, but to vindicate an assertion of such consequence would require detailed examples of how and when the jettisoning could be done rather than facetious rhetoric. The only example provided of ‘amoral social behaviour’ is climate change activism, and the most Paley establishes is that so far it has been ineffective.

Yet Paley allows that morality has been useful after all. Its function is to change people’s behaviour, and that requires gauging what they want and intend. “What we glean [of others] is a product of our own brains as much as theirs”, says Paley, and, equally, we each have to construct our own self-model ‘from the outside-in’ – via what others have fabricated of us. Even pain, says Paley, is largely an ‘inference’ as to ‘what others would infer’. Indirectly, then, morality has provoked the development of minds.

But, if minds are just a mutual collusion concoction of mirages, how can ‘getting minds right’ be important, or even possible? Paley inadvertently suggests that there is some (physical, neural) reality at the core of the smoke and mirrors, and that we need to conjure ideas of our own and other people’s thinking only because “we don’t [as ideally we should] carry around brain scanners with which to probe the inside of others’ heads.” Yet we’d be no wiser if we did. Observing neural imaging would in itself be uninformative without accumulated, systematic correlations, by neuroscientists, between what is observed in brains and what is reported by brain-owners. Paley’s mind-fabrication argument, though intriguing, is circular.

Perhaps I should feel guilt at reviewing this book so harshly. Since, however, it exhorts me to ditch my morals, I’m without compunction.

© Jane o’Grady 2022

Jane O’Grady helped found the London School of Philosophy and writes philosophers’ obituaries for The Guardian. She co-edited Blackwell’s Dictionary of Philosophical Quotations with A.J. Ayer, and wrote Knowledge in a Nutshell: Enlightenment Philosophy (Arcturus, 2019).

• Beyond Bad: How Obsolete Morals Are Holding Us Back, Chris Paley, 2021, Coronet, £11.99 hb, 272 pages, ISBN 9781529327090