Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Political Philosophy

Cultural Colonialism & Aesthetic Injustice

Gustavo Dalaqua on decolonizing minds.

My first sight of an openly gay man was on television. In my early teens back in the late Nineties, almost every Saturday evening, my family and I would watch A praça é nossa, one of the most famous comedy shows in Brazil. Vera Verão, played by Jorge Lafond (1952-2003), a black gay man, was one of our favorite characters. Her sketches varied considerably. Sometimes, her race was the main reason for mockery. In other sketches, what led viewers to chuckle was Vera Verão’s fights with the women whose men she wanted to have. Yet despite their differences, a common event present in all sketches that Vera Verão played is that someone with disgust calls Lafond ‘ bicha’ (‘faggot’). This was the moment my parents, my sisters, and I laughed the most: the moment when Lafond was humiliated for being gay. It is not surprising, then, that the Grupo de Gays Negros da Bahia (Group of Black Gay Men from Bahia) protested when the government announced that Lafond was chosen to advertise a public campaign against STDs among homosexuals. According to them, Lafond should not have been chosen because his work as a performer disseminated racism and homophobia.

What does Vera Verão have to do with ‘cultural colonialism and aesthetic injustice’? To answer this question, it is necessary to first explain what each term means.

Cultural Colonialism & Aesthetic Injustice

Augusto Boal in 2008

Image © Annmari 2008 CC

Cultural colonialism and aesthetic injustice are two related phenomena examined by the Brazilian cultural theorist and activist Augusto Boal (1931-2009). By cultural colonialism, Boal means the oppression that remains in the realm of culture even after the end of formal political colonialism. To put it in a nutshell, it is a practice of either promoting or denigrating different cultures in a way that begets oppression.

In his 2009 book The Aesthetics of the Oppressed, Boal mentions the legendary singer and actor Carmen Miranda as an example of cultural colonialism. Miranda, who abandoned her artistic career in Brazil to try her luck in Hollywood, became in 1945 the highest-paid entertainer in the United States. Dancing with bananas and pineapples on her head, Miranda personified like no one else the Latin exoticness created by Hollywood. The Brazilian characters she played on the screen confirmed to the mainstream US public their stereotypes about Latinx and Latin American people and helped consolidate an image of Latin culture that is still believed by a significant number of Anglo-Americans today.

In Theatre of the Oppressed (1979), Boal gives two other examples of cultural colonialism. The first one is Old West movies – classic Westerns – which were popular among the youth in Mexico when Boal was writing his book. Boal argues that these movies made young Mexicans sympathize with the foreign cowboys’ perspective: “Through empathy the children abandon their own universe, the need to defend what is theirs, and incorporate, empathically, the Yankee invader’s universe, with his desire to conquer the lands of others.” The second example Boal cites is Sesame Street, an educational program that, according to Boal, sought to help poor families by teaching their children the importance of working hard and saving money. This is cultural colonialism because, by internalizing the discourse that the privileges of the wealthy were the fruit of merit and effort, the poor tended to accept social inequality. The oppressed become docile when they see the world through the oppressors’ lenses.

As the Sesame Street example indicates, cultural colonialism can happen not only between countries, but also within a single country, if only because no country has a completely homogenous culture. Racism and misogyny also provide examples of cultural colonialism expressed among the inhabitants of the same country.

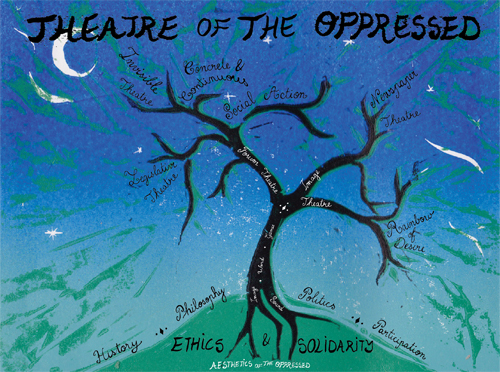

Branching Away from Aesthetic Injustice by Rose de Castellane 2022

Image © Rose De Castellane 2022

Aesthetic injustice designates the atrophy of aesthetic capacities caused by oppression. By aesthetic capacities, Boal means our abilities to feel and perceive things. Oppression changes the way we perceive and feel things. The cultural structures that perpetuate oppression in thinking generate certain modes of feeling that stunt the epistemic and aesthetic capacities of the oppressed. Indeed, such manipulation of their experience is instrumental in maintaining oppression. In order to remain in power, every system of oppression must hold sway over people’s desires, affections, and thoughts. Of course, oppression is also transmitted through socioeconomic structures such as the police, banks, courts, schools, and legislative assemblies. Yet these apparatuses only work as conduits for oppression because of the people who occupy and operate them. If policemen, bankers, judges, teachers, and lawmakers began to feel, perceive, and think in ways incompatible with capitalism, racism, etc., it would not take long for these modes of oppression to crumble. We can say that the structural aspect of oppression remains operative to the extent it finds shelter in people’s subjectivity.

Some philosophers today study ‘epistemic injustice’, by which they mean any harm done to someone specifically with regards to their capacities to know things. Few philosophers, however, have paid much attention to aesthetic injustice. This neglect is troublesome because epistemic injustice feeds on aesthetic injustice, since your capacity to know is dependent on your capacity to perceive and feel. To be sure, one of the major contributions that Boal has to offer contemporary philosophy lies in his demonstrating that effective resistance against epistemic injustice requires tackling aesthetic injustice. Yet aesthetic injustice is in its turn provoked by cultural colonialism, because by preventing different cultures or subcultures from being appreciated, the aesthetics of the ‘superior’ social group smothers the aesthetics of the ‘inferior’ people. Cultural colonialism treats the oppressors’ aesthetics as if it were the only valid form. Lafond did not protest to his being humiliated due to his race and sexuality because he had been culturally colonized.

Resisting Cultural Colonialism

The rage some LGBTQI+ people felt toward Lafond is understandable. I also ask myself whether accepting my sexuality would have been less difficult if Vera Verão and similar culturally colonized characters had not existed in my youth. Lafond gained fame and money with his work, yet harmed many people by turning himself into an active perpetrator of racism and homophobia. Nevertheless, we should not forget that he was both oppressor and oppressed. Westernism, racism, homophobia, and other types of cultural colonialism, can only guarantee their predominance because they find support in the desires, affections, and thoughts of the majority of a culture, including those who are demeaned by them. As Boal put it, “whatever its type, oppression can only sustain itself because it is accepted by its victim. We are oppressed because we are somehow willing to make concessions” (Games for Actors and Non-Actors, 2002).

Lafond was an oppressed person who made concessions to the oppressors, and his complicity came at a high price. In 2002, he was playing Vera Verão on a live TV show when he was asked to leave the stage because Marcelo Rossi, a Catholic priest who was about to participate in the show, refused to appear publicly with him. Marcelo Pádua, who was then Lafond’s manager, recalls that a few minutes after being expelled Lafond had a nervous breakdown. He was sent to a hotel, where he remained in severe depression, almost without leaving the bed. Pádua became increasingly worried and, after a week, took Lafond to the hospital. The doctors diagnosed heart problems in Lafond and decided to hospitalize him. A few weeks later, in the hospital, Lafond had a heart attack and died.

Cultural colonialism and aesthetic injustice kill people. Lynchings, police violence, and suicide are examples of practices exacerbated by cultural colonialism and aesthetic injustice which exterminate many lives. Even in their less extreme manifestations, cultural colonialism and aesthetic injustice go against democracy, for they deny citizens’ equality. It is therefore imperative to investigate them and to study how we can resist them. How can we promote cultural decolonization and aesthetic justice?

A Mappe of ye Colony Ricardo da Luig, 1621

Before answering this question, I should point out that the latter cannot come to pass without the former. Since aesthetic injustice is produced through cultural colonialism, aesthetic justice requires cultural decolonization. Therefore, creating aesthetic justice will involve the development of either an environment or a type of confidence that allows people to feel and perceive the world in ways that do not segregate their own culture into an ‘inferior’ camp. Cultural decolonization is conducive not only to aesthetic justice, but to justice generally, for it permits people to interact with human diversity without turning their differences into a matter of ranking.

Cultural decolonization is furthermore a collective process of dismantling the social hierarchies furthered by cultural colonialism, such as the hierarchies of racism and sexism. We should keep in mind that not all of the groups privileged by cultural colonialism are willing to renounce their superior status. If an erstwhile ‘inferior’ cultural group is accorded the same value as other groups, then that means the latter have lost their superior standing vis-à-vis the former. So, for instance, the conservative philosopher John Finnis is right to claim that recognizing same-sex unions as marriages will thereby diminish the value of heterosexual marriage (Law, Morality, and Sexual Orientation, 1997).

In his books Boal elaborates techniques for promoting cultural decolonization and aesthetic justice. The ‘rainbow of desire’ techniques, for instance, were created by Boal (The Rainbow of Desire, 1995) to help the oppressed resist in a specific domain where cultural colonialism thrives, namely the domain of our desires. When we are under the boot of cultural colonialism and aesthetic injustice, most of us end up desiring the colonising cultural product, and find it difficult to appreciate aesthetic diversity. This is why most Latin Americans listen to Anglo music instead of, say, indigenous music, and it also explains why most people generally watch romantic movies that feature straight couples, not those featuring same-sex couples. Boal says that our desires are not unitary, but contain many different colours like a rainbow. The colours of this spectrum can be picked apart and recombined in different ways. So Boal developed a set of techniques using theatre and therapy to do just that, and thereby to decolonise desire.

Teatro do oprimido e outros babados (Theatre of the Oppressed and Others), edited by Flavio Sanctum and Helen Sarapeck, illustrates remarkably well how the rainbow of desire technique can accomplish cultural decolonization and aesthetic justice. In one chapter, Sanctum describes how the technique helped him accept his sexuality. Before practicing the technique, Sanctum could not explore his desires because he felt that heterosexuality was superior to homosexuality. Nowadays, Sanctum no longer feels ashamed of being gay. Moreover, through the use of Boal’s legislative theatre, he drafted a petition that asked Rio de Janeiro’s city councillors to create a law establishing a fine for restaurants that refused service to customers on the basis of their sexuality. Enacted by the Municipal Council of Rio de Janeiro in 1996, law 2475 was the first anti-discrimination law in Brazil that specifically protected LGBTQI+ people. Resisting cultural colonialism and aesthetic injustice requires transforming not only our subjectivity, but also the structures that shape it.

© Gustavo Dalaqua 2022

Gustavo Dalaqua is a professor in the Department of Philosophy at Universidade Estadual do Paraná, a member of Coletivo Paulo Freire de Filosofia, and a fellow of the Brazilian Center of Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP).