Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Classics

Existentialism is a Humanism by Jean-Paul Sartre

Kate Taylor recalls a ‘humanist’ classic by Jean-Paul Sartre.

Jean-Paul Sartre’s short book Existentialism is a Humanism (1946) sets out the main claims of Sartre’s existentialism, and defends these against some of the criticisms laid against it.

Sartre makes two basic claims – firstly that God is dead and this has consequences for the way we live; and secondly that all claims about humanity and the world must begin with human experience. Given these two claims, Sartre concludes that ‘existence precedes essence’. What he means by this is that human beings are without any pre-existing purpose or ‘essence’ which is not of their own making.

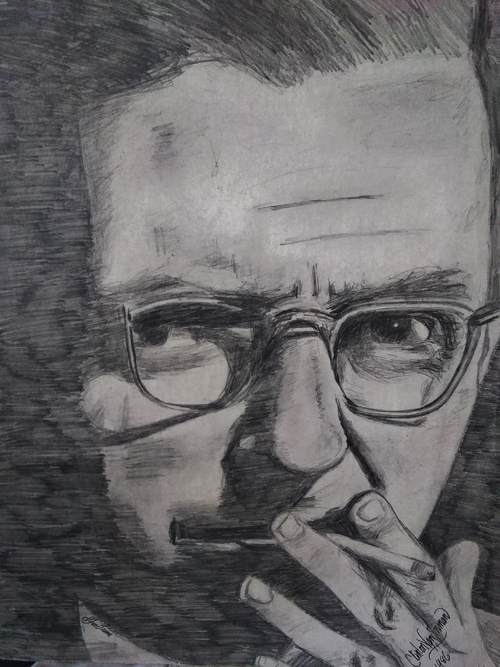

Jean-Paul Sartre by Clint Inman

Portrait © Clinton Inman 1986 Facebook at Clinton.inman

Let’s explore these claims some more.

If we think about an everyday manufactured object – let’s say a chair – we can see that it has been made with specific qualities in order to carry out a specific purpose: as something for us to sit on. Even before he goes about making it, the manufacturer of the chair already has in mind what he wants the chair to look like, the types of qualities that he wants it to have. This specific set of qualities exists before the chair exists, in the mind of the manufacturer. Sartre thinks that when we talk of human beings having a specific essence, we are making the assumption that we, like the chair, have been made according to a specific set of qualities in order to carry out a specific purpose. In other words, we assume that even before we are born what we are – our essence – already exists in the mind of our supernatural manufacturer, that is, God.

But if God is dead, this cannot be true. So since he is an atheist, Sartre says that existence precedes essence: unlike the chair, we do not come into existence with a specific set of qualities in order to carry out some or other purpose. Rather, the responsibility falls solely on us as individuals to make our purpose for ourselves. In the absence of a supernatural manufacturer, we make ourselves.

But how, without a manufacturer’s blueprint, do we go about making ourselves? For Sartre, the answer to this question is what defines existentialism as a philosophy of action: we live through our freedom of the will to choose. This brings us to the second of Sartre’s core assertions: that all claims about humanity and the world must begin with human experience.

It was René Descartes three hundred years earlier who concluded that the primary thing we cannot doubt is that we are thinking things: ‘I think, therefore I am’. For Sartre, it is this human subjectivity – our lived experience – that underpins his claim that we have the freedom to choose how to act. Sartre says that our lived experience shows us that we are always free to choose to act upon this or that. Think about the next choice that you make: you could stop reading this article, or continue, or get up and get a glass of water; take the dog out; get some ice-cream, and so on. The point is that our lives are always filled with possibilities, and we are free to choose which ones to take.

This takes us on to Sartre’s moral point: by choosing this or that, we at the same time choose the set of values endorsed by our choices. This is because, for Sartre, we can’t choose something that we don’t think is good, therefore each choice is also an affirmation of the value of what we choose. This kind of potential pick-and-mixing of values has faced criticisms for being overly individualistic. But for Sartre, our freedom cannot come without responsibility, because all choices have consequences, and his defence against criticisms that existentialism is an extreme individualism is the radical claim that individual choices legislate for humanity as a whole. Sartre believed that in choosing this or that, we at the same time validate that choice for the rest of humanity. In this way, human beings are not only responsible for making themselves, we are also responsible for defining humanity as a whole.

In a post-God world, only human beings can choose what to make of their existence. Sartre in fact says that we are ‘condemned to be free’. Our freedom is a condemnation because we cannot escape having to choose, nor escape the responsibility that comes from having that capacity. We cannot deny the weighty responsibility that accompanies our freedom to will as we choose.

© Kate Taylor 2022

Kate Taylor is a writer, clearly.