Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

The Ahuman Manifesto by Patricia MacCormack

Stephen Alexander is against a work against humanity.

The full title of MacCormack’s book is The Ahuman Manifesto: Activism for the End of the Anthropocene. It may be about the end of the era of human beings, but according to the Preface, it is intended to be an optimistic work of joy and radical compassion, with ‘radical compassion’ being interpreted as a form of grace to be extended to all life on Earth. Its position is a counternihilism that affirms (amongst other things) queer feminism, atheist occultism, deep ecology, and human extinction. In other words, it’s ethics, Jim, but not as we know it.

MacCormack’s central argument is simple: “It is time for humans to stop being human. All of them” (p.65). But that’s easier said than done. You can’t tell someone who has the flu to ‘just get over it’; neither can we just shake off our humanity. What’s more, the demand is controversial because there are many who are still waiting for their humanity to be fully recognised and are still keen to assert themselves as subjects. But MacCormack insists that we can all exit the world in perfect harmony, so long as we agree to abandon the ‘phallo-carnivorous’ realm of the malzoan [‘bad life’, Ed.]

MacCormack is probably right to suspect that for many readers the idea of the death of humanity will be an absurd and troubling proposition. But if, on the one hand, she desires a human-free future, on the other hand she also wants to avoid despair and retain her political commitment to something that seems rather like old-fashioned humanism and its values. For example, any form of discrimination, such as racism, remains abhorrent, presumably on the grounds that it lacks compassion.

Equally troubling for some will be MacCormack’s rejection of personal identity, which she describes as a peculiarly anthropocentric obsession. That’s certainly at odds with the spirit of the times, and I admire her willingness to be untimely, even at the risk of being branded a traitor to the human race.

Ultimately, MacCormack doesn’t care about interhuman arguments over identity, social justice, or even animal rights; she cares about the “reduction in individual consumption of the nonhuman dead” (ie vegetarianism). If she retains a notion of equality, for example, she asserts that it is “as much of a myth as the humanist transcendental subject” (p.51). But surely better this myth of equality than giving humanity over to structured inequality, for hierarchy is a life-denying form of categorisation that restricts freedom and the potential of the individual to develop.

Having said that, MacCormack is also contemptuous of the idea that inanimate and inorganic objects might be seen as having a degree of agency. She calls it “a tedious inclination in certain areas of posthuman philosophy, where a chair is no different to a cow or a human” (p.56). Now, I’m no object-oriented ontologist, but I’m pretty sure that’s an unfair characterisation of their work. Contrary to what MacCormack says, those speculating in this area argue not that all objects are equal, but that they are all equally objects. Further, as a Nietzschean, I’m tempted to remind MacCormack that being alive is only a very rare and unusual way of being dead and that to discriminate between living beings (cows) and inanimate objects (chairs) is, therefore, ultimately a form of prejudice.

I can’t help seeing this as the point at which her moralism triumphs over her own confessed worldview, for instance, over her model of queerness – triumphs over and, indeed, infiltrates it: “Queer in my use is… about the death of the human in order for the liberation of all life…” (p.60). That’s one definition, I suppose. And, in as much as ‘queer’ does mean ‘rare and unusual’, then yes, life is queer – but then that would surely include human life. Hasn’t she heard the old Yorkshire saying that “There’s nowt so queer as folk”?

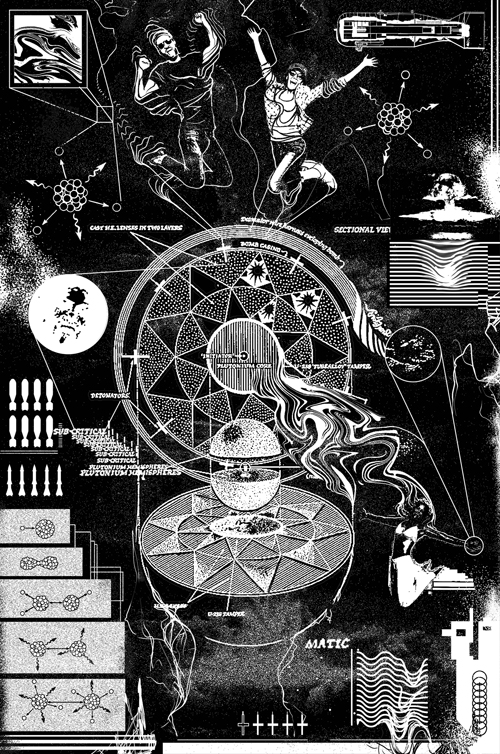

Illustration © Jaime Raposo 2021. To see more of his art, please visit jaimeraposo.com

Chapter 2 of The Ahuman Manifesto explores redefining aesthetics to enhance the ethical nature of activism. Alas, I fear that MacCormack is mistaken to pin her hopes on art as something that occupies a “privileged space of knowing/unknowing” (p.69) which is distinct from the epistemological spaces occupied by science and philosophy. Baudrillard was right; at best, all we can do in this era of transaesthetics and self-reference is ‘act out the comedy of art’.

I also think she’s mistaken to articulate her project in the religious terms of hope, faith, and belief – or what MacCormack calls ‘non-secular intensities’. As an atheist, I can accept an ethics of care, compassion, and even grace; but I’m not about to embrace the virtue of hope, for example, and it’s ironic to see MacCormack affirming something that only serves to prolong human existence.

In Chapters 4 and 5 MacCormack offers us alternative escape routes from anthropocentrism – the first occultural and the second thanatological.

For those who don’t know, thanatology is the study of death and its implementation; and occulture is “the contemporary world of occult practice which embraces a bricolage of historical, fictional, religious and spiritual trajectories… an unlimited world of imagination and creative disrespect for… hierarchies of truth based on myth or materiality, law or science” (pp.95-6). It is also apparently a ritualistic method of catalysing ahuman becomings, which leads onto a paradoxically vital and compassionate form of ‘death activism’ that posits “the death of the human body in its actual existence more than just a pattern of subjective agency” (p.141). In other words, this is the death of man as species, conceived as “a necessity for all life to flourish and relations to become ethical” (p.140).

This is an idea I’m certainly familiar with, and to which I’m vaguely sympathetic. Where MacCormack and I part company is on the topic of human abolitionism. For whilst I don’t subscribe to human exceptionalism, as a Nietzschean I accept that life is founded upon a general economy of the whole, in which certain terrible aspects of reality – cruelty, violence, and exploitation, for example – are indispensable. MacCormack may address this idea elsewhere, but, as far as I can see, she entirely fails to do so in The Ahuman Manifesto. Instead, she adopts a fixed, unexamined and, ironically, all too human moral standpoint throughout the book from which to pass judgement: on men, on meat-eaters, and on those she denigrates as ‘breeders’. Even when she does attempt to get a bit Nietzschean and celebrate death as an absolute Dionysian frenzy, she quickly adds a proviso: “the celebration of the corpse and of death here is entirely mutual and consensual.”

Ultimately, her dream is “to create an ahuman thanaterotics based on love, not aggression” (p.158). By that she means a ‘death love’ free of misogyny, racism, and of the angst-ridden pessimism of the typical white male, who can only rather insensitively imagine necrophilia and cannibalism in the savage, sensational and pornographic terms of the serial killer. But in MacCormack’s ‘thanaterotics of love’, the corpse can be sexually used, or served with fava beans and a nice bottle of Chianti; but only if the corpse has not been produced against its own agency via anthropocentric violence. So her ahumanism is not philosophical nihilism, but a form of ethical affirmation, and a form of freedom, albeit it’s the freedom to be eaten or to become a necrophile’s object of desire.

The closing chapter of The Ahuman Manifesto is an apocalyptic conclusion stained with tears ‘of love and joy’ (p.191). And other than cry, there’s precious little left for us to do now anyway, says MacCormack: nothing except manage our own extinction, and act as kindly caretakers for the planet. Which sounds all a bit like Nietzsche’s Last Man, does it not?

Oddly enough, MacCormack quotes from Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra and suggests that her compassionate model of apocalypse is in tune with his message of creating beyond the self. But it’s hard to see anything Nietzschean about her ahumanism. Indeed, it’s arguably no more than another unfolding of the ‘slave revolt’ in morals: one that speaks of love and joy, but is shot through with ressentiment and a refusal to accept that nothing is tastier than a tender lamb.

© Dr Stephen Alexander 2022

Stephen Alexander is a London-based writer with a PhD in Modern European Philosophy and Literature. He blogs at torpedotheark.blogspot.com.

• The Ahuman Manifesto, Patricia MacCormack, Bloomsbury Academic, 2020, £21.99 pb, 224 pages