Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Society & Reason

One Logic, Or Many?

Owen Griffiths and A.C. Paseau try to count them.

Ours is a pluralist age. There is no one right way of doing things, but many; no one set of beliefs, but a diversity; no one true religion, but a host of equally legitimate faiths. We can, and should, live our lives as we wish to, according to our individual aims and values – within broad limits.

That is a credo many of us would sign up to. But even if you subscribe to the diversity manifesto, are there many correct ways of reasoning? Is it up to us how we reason? Can we do it one way or the other, depending on our inclination, mood, or perspective?

To answer these questions, we must be clear on what reasoning involves. At the heart of reasoning lies logic, a subject almost as old as philosophy itself, and one of its major branches. Aristotle invented the study of logic in about 350 BC. He systematised a range of logical arguments he called ‘syllogisms’, including ones of this form:

All influencers are exhibitionists.

All exhibitionists are shameless.

Therefore: all influencers are shameless.

In a syllogism, such as this one, the first two sentences are the argument’s premises, and the third, following ‘Therefore’, is its conclusion, and the conclusion follows inexorably from the premises. You will have guessed that this example was not Aristotle’s; but it is in the form of an argument he recognised and described.

The study of syllogisms occupied logicians for many centuries. Medieval philosophers even had nicknames for the various types of syllogism. The one above was known as ‘Barbara’, because the name’s three vowels serve as a mnemonic for the first word in each sentence: a ll, a ll and a ll.

Aristotle clearly seemed to think there was a right way and a wrong way to reason. The various syllogisms he discussed were at the core of his logic; and, for him, there were no two ways about it: if you believe the premises, you’d better believe the conclusion. As he puts it in his Prior Analytics, a syllogism is a form of discourse “in which, certain things having been supposed [the premises], something different from the things supposed [the conclusion] results of necessity because these things are so.”

Observe that Aristotle says that the conclusion must follow from the premises of necessity. Neither of your authors has a direct line to Aristotle, but we are confident he would have been shocked at the suggestion that there is more than one correct way to reason.

However, ‘reasoning’ is a broad category. It comes in many guises, not all logical. If you live in a dry land where there has been little rainfall in winter, you will reasonably conclude that a drought will follow this coming summer if summer droughts have followed dry winters very reliably in the past. But the conclusion does not follow of necessity from the premises: Spring could confound expectations and turn out to be wet. Your reasoning is not (excuse the pun) watertight.

So what’s special about logical reasoning? We agree with a great many philosophers that it has something to do with form.

Try out the following experiment. Find someone who doesn’t know the meaning of the word ‘ungulate’, then ask them whether in the following argument (‘Barbara’ again) the conclusion follows from the two premises.

All ungulates are mammals.

All mammals are warm-blooded.

Therefore: All ungulates are warm-blooded.

We regularly try this out on our students, and always get the same result. Many students don’t know what ‘ungulates’ are – but they all recognise that the argument is valid: that the conclusion inexorably follows from the premises: that if what the premises say is true, then the conclusion has to be true.

So what does this show? It shows that logical validity depends on form. Therefore, to recognise an argument’s validity, you have to recognise that it has a valid logical form; you needn’t know anything else.

So logic is formal. It is also, strictly speaking, not a theory of reasoning. Reasoning is something we do; logic is about what statements follow from others. Logical relations among statements hold (or do not hold) whether we like it or not, whatever we might think; indeed, whether any of us are around or not. Logic is not anthropocentric. And when we reason well, we ought to respect the implications of logic. If some plausible premises logically imply an implausible conclusion, we have a choice: we can either embrace the conclusion or abandon one of the premises.

So that’s what logic is: it is formal, and it is distinct from reasoning, even if good reasoning tries to respect logic.

And so we return to our original question: Is there one correct logic, or are there many?

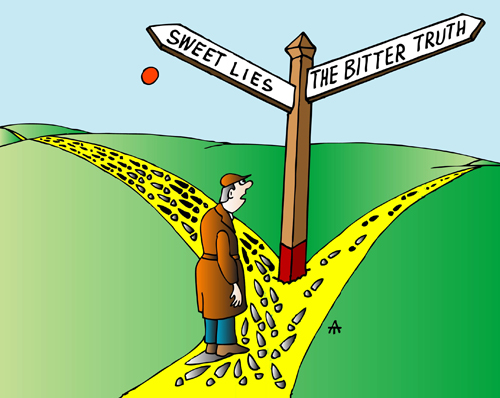

Cartoon © Alexei Talimonov 2023 Email: talimonov.a@hotmail.com

Logical Possibilities

This might seem like a strange sort of question. You’ve heard of logic, but perhaps not logics. Let’s start by thinking about why there might be many.

Our logic students don’t only learn about ungulates. They also learn various controversial logical principles that cause bemusement. One of the first principles they typically baulk at is bivalence: the idea that every sentence is either true or false. Surely not, they protest, since there are myriad examples that don’t fit into this strict binary. If I say “ The Power of the Dog is a beautiful film”, surely I haven’t said something true or false; rather, it’s a matter of opinion – and similarly for other matters of taste, such as “This is a tasty burger.” Perhaps ethical language also goes against bivalence. Is ‘Hurting puppies is wrong’ strictly true or false? Or does it instead express the speaker’s disapproval of hurting puppies? If so, it’s starting to look more like a matter of taste again. Fictional discourse also provides further problems for bivalence. Is ‘Sherlock Holmes lived in Baker Street’ true? On the one hand, there is no Sherlock Holmes, so how can it be true? On the other, it seems more true than ‘‘Sherlock Holmes lived in Oxford Street.’’

If you are moved by any of those examples, you’ll think that bivalence doesn’t hold exceptionlessly. But we want logic to hold exceptionlessly, so bivalence couldn’t be a principle of logic. This might motivate you to look for a logic in which bivalence doesn’t hold. You might think there’s some third way sentences can be, other than true and false; and maybe there’s even a fourth way they can be; or maybe there are infinitely many ways. Whichever way you choose, you can construct a logic to suit your needs.

And the problem examples multiply. As a budding logician, you’ll also learn that contradictions can never be true, even though you might think ‘It’s raining and it’s not raining’ is a perfectly reasonable description of drizzle. You’ll learn that contradictions explode and entail anything and everything. Allow contradictions and in no time you’ll be finding that: ‘If the Moon is made of cheese, then the Earth is flat’ is true.

The first logic anyone learns about – and which includes all of these disputed principles – is called classical logic. The name is quite the PR coup: it puts this logic in the elevated company of classical music or the classics of French cuisine. But, as proponents of non-classical logics will be keen to emphasise, it might be no more than a historical accident that we’ve ended up with the logic we have. They might add that there are many logics on the market, all rejecting some part of classical logic found to be suspect. Which of them should we use?

Perhaps we can use all, or at least many, of them. Perhaps we can reason classically most of the time, but non-classically when the mood takes us. This is the line taken by logical pluralists. Let a thousand flowers bloom, there’s no need to choose between them!

However, the logical pluralist is in a delicate situation. They want to argue for their view, but what tools can they use to do so? Argument is, after all, the domain of logic, and what is logical is precisely what is at issue.

This situation may seem familiar. Earlier we mentioned the possible denial of moral facts. Though there are many ways to develop that view, one well-trodden path is moral relativism, whereby moral claims are never true ‘all by themselves’ – rather, you must specify a cultural or individual standard by which the claim can be assessed. It’s never just ‘Such-and-such is really right (or wrong)’, but ‘According to this culture or this person, such-and-such is right (or wrong)’.

Moral relativism faces many problems, but one of the most relevant is that it seems to undermine itself. It says that moral claims are only true according to some culture or person. But the statement of moral relativism is surely itself a moral claim, and a universal one, too. So it is true only according to some non-relative standard: the moral relativist intends moral relativism to be true absolutely, not just relatively. They effectively want to say ‘Every moral claim is true only according to some relative standard, except this one’. But that’s cheating.

What can this story about moral relativism teach us about logic? Well, we might see the logical pluralist’s situation as analogous to the moral relativist’s. The logical pluralist believes that their position is true, and they want to convince you the same. But if they’re to convince you, they’ll need to offer some argument. And that argument had better be valid. But they endorse many logics, and only think of arguments as valid relative to a chosen logic. So they effectively want to say: ‘Every argument is valid only according to some chosen logic, except the argument for logical pluralism’. That’s also cheating.

Perhaps this similarity shouldn’t surprise us too much. Moral relativism is often characterised as a kind of pluralism. The moral relativist wants to let a thousand flowers bloom, morally speaking. And the logical pluralist is often characterised as a kind of relativist. They want to assess whether an argument is valid relative to some chosen logical system. So we might expect arguments against one system to find counterparts in arguments against the other (and the point generalises to other forms of pluralism/ relativism, too).

Where does that leave us? If logical pluralism isn’t an option, then we must choose one of the logics, and defend it as the one true logic. One obvious next question: if there is just one valid logic, which one is it?

Well, that’s a question for another day.

© Owen Griffiths, A.C. Paseau, 2023

Owen Griffiths and A.C. Paseau are both philosophers of logic, among other things. Their book One True Logic was published by Oxford University Press in May 2022.