Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Fiction

The Free Will Exam

Luke Tarassenko’s hero finds himself at a testing time.

We entered the hall one after another in silence, found our names and numbers, and sat down at our allocated desks. Being a Buckland, it was always easy to find my place, usually near the entrance to the hall and quite close to the front.

My chair scraped a little as I pulled it out. I assembled my writing implements on the desk, in a ritual that I was now well accustomed to. In front of me, Black did the same. Behind me, Burrows no doubt followed suit – and gave his familiar little sniff, which now triggered off in me a Pavlovian reflex of extreme irritation. I set my jaw, held my head high, and stared straight ahead. Inside, I was terrified.

One of the invigilators came round with the exam paper. The sweat dripped down my brow, my neck, my back, starting to lather my shirt. I wanted to shiver, but I held it in. The invigilator placed the paper on my desk.

‘A LEVEL PHILOSOPHY: METAPHYSICS’ stared at me in bold typeface. ‘TIME ALLOWED: THREE HOURS’.

Don’t mess this up. Don’t make any stupid mistakes. Your whole future depends on this exam.

“We don’t need no education!”

Schoolboys © State Library Of Queensland public domain

I’d done well enough in my other subjects to know that I would meet the required grades for university entry. But since I especially wanted to study Philosophy, there was special pressure here. I needed to get at least an A or preferably an A* in this subject – and in this paper – to get the place I wanted. What I would write in the next three hours was going to affect the whole course of my life, in one way or another. It would affect where I went for the next three or four years; whom I met; what kind of degree I would end up with; how impressive my CV would look; and what my future job prospects would be. Probably affect who I ended up marrying, and what religion I took up as well. It was almost too much to bear. Why did so much have to pivot on this one little one-hundred-and-eighty-minute chunk of my existence?

The chief invigilator began to read out the usual rigmarole. I knew it off by heart by now; but in any case it was drowned out by the fear that threatened to overwhelm my mind like so much white noise. My brain whirred into action just as he uttered the magic (death) sentence: “You may begin.”

There was a sound of eighty pieces of paper being turned over at once. My eyes darted straight for the relevant area. I always liked to do the longest, highest marks essay questions first, when I was freshest, to get them out of the way.

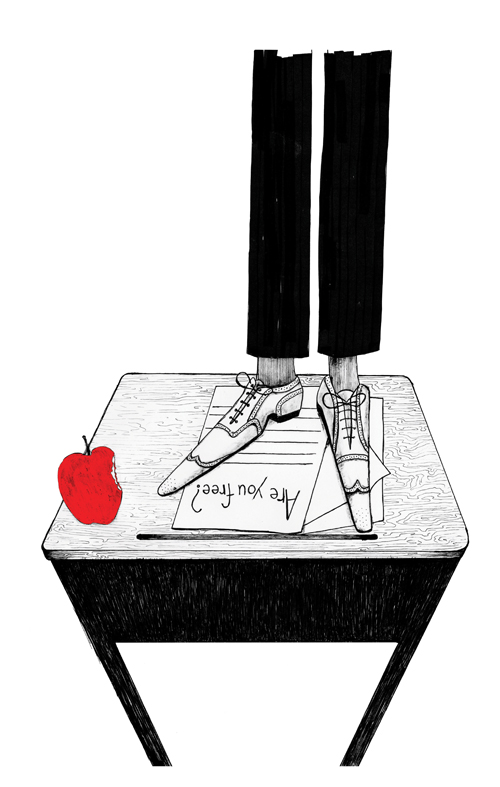

5. Are you free? (25 marks)

I almost laughed out loud. This was my question. Little did the examiners know, but this question was the whole reason I had chosen to study Philosophy at school in the first place, and the whole reason why I wanted to study it at university. I was obsessed with the problem of free will versus determinism, and wanted to solve it. What a stroke of predetermined luck that this question had come up – and phrased in just this way!

I knew what was required of me: I must write a brief introductory paragraph, then quickly outline the different positions: determinism, libertarianism, and compatibilism, along with their various pros and cons; make some evaluative comments along the way; then sum up my assessment in a concluding statement which advocated one of the positions on free will and explained why. Simple.

I sketched a very quick essay plan in note form on the exam paper itself, next to the question, writing in one-word reminders of criticisms and counter-criticisms I would call upon in order to make my argument. All the while my hand moved on what felt like autopilot, feverishly scratching the plan etched into my neurons during revision onto the page so that I wouldn’t have to keep summoning it up from my memory while writing my answer. Must be fast. Whole future depends on this. Must write quickly.

Then I opened my answer booklet. The first thing I did here was write down the question, so that the examiner would know which one I was answering first:

5. Are you free?

It’s a punchy wording of the problem. In the past papers I’d looked at while revising, usually the problem of free will was posed in much more removed and abstract terms. Strictly speaking, to answer this question on its own terms, I would have to speak in the first person – though of course I would maintain academic style by extrapolating from my individual case to throw in some statements about humanity as a whole, and perhaps also make a nod to the notion of political freedom.

I looked at the question again. Without warning, it morphed in my mind. The appearance of the letters on the paper even twisted and changed so that I read it slightly differently:

Am I free?

My arm went rigid. Confronted by that question, suddenly I couldn’t move, or even think clearly. The three words resounded through my head as I sat staring at them on the page in front of me.

After a while, slowly, with effort, I glanced to my left. I don’t know why I glanced to my left. Did I do it on purpose, or was I causally determined to do it? Or both? Anyway, on my left was Alistair Crawford, furiously writing away, with no thought as to why he was doing so, as to whether this was what he really wanted to be doing, or whether he had freely chosen this course of action: school, exams, University, job… He was just doing what he had been told to do, without questioning it or reflecting on it – just getting swept along in the stream of society like everyone else, carried along by the currents mindlessly, thoughtlessly, helplessly. Just another part of the machine, whirring away, ticking over. One more cog, one more slave submitting to constrictive cultural constructs.

Image © Susan Platow 2023 Please visit SMPlatow.com

I considered the question again:

Am I free?

It was too much. No, I wasn’t free, clearly! But I was going to see to that: I was going to change all that. Enough was enough.

I let out a shout of desperation as I decided that I wasn’t going to let myself be coerced any more. Actually it came out as more of a scream. “ I will become free!”

At once every pair of eyes in the room was on me. There was a brief, beautiful moment of shock – a collective intake of breath in which the sacrilege of what I’d just done took effect. I had violated the exam-taking covenant; I had broken the unspoken law of unspeaking. That was enough to snap them all out of their collective hypnosis. Perhaps all it takes is one person to be big enough, brave enough to stand up to the system and fight, to rally the troops to throw off the chains of this hateful scholastic oppression, and maybe we really could be free!

The invigilators started walking towards me. Because they were British, and this was an exam, they walked instead of ran. Meanwhile, I climbed up on my chair and then used it to mount my desk. Then I made a speech that went exactly like this:

“Friends, fellow students, vague acquaintances! You do not need to live like this! When did we sign up to be trapped in an endless system of tests and exams which will only lead us on to more soul-destroying work? Who made us slaves to this assessment machine, ants forced into a maze of grades and performance reviews that we’ll stay trapped inside our whole lives? Whoever asked you if you wanted to become a racing rat? We could live for so much more than this –” At this point one of the invigilators reached my desk – a stern-looking middle-aged woman with half-moon spectacles and hair tied back in a bunch. She was trapped in the machine too, just as antsy and ratty as everyone else. “Silence, boy!” she said. “Come down from there at once!”

But I still had everyone’s attention, so I carried on: “Don’t listen to these insects! They’ve been brainwashed! And you have too! Why does no-one question why we’re here, being made to do these tests? It’s an injustice. It’s cruelty! But we don’t have to accept it. We can rebel! We can claim our rightful freedom!”

Some of the other students raised their eyebrows. Some of them sighed exasperatedly. A few of them – the ones that were closest to being my friends – rolled their eyes. Someone said, “Shut up, Theo! We’re trying to sit our bloody A-levels, for God’s sake!”

Now one of the other invigilators got to me. Because I hadn’t responded to the vocal warning, he grabbed my wrist in an effort to bring me down. I paused my speech and kicked him. He reeled back, releasing his grip on my wrist and grasping his nose in pain. I became more urgent with my audience: “Rise up! Rise up! Throw off the shackles of this tyrannical oppression! This is not freedom! You could live for so much more! We don’t have to let ourselves be forced into this anymore! Think for yourselves! Make the choice! You can cast off this educational regime! Loose your fetters!” Now backup arrived, as a flurry of teachers came through the double doors, having been fetched by one of the invigilators. “Look what they do to those who step out of line!” I said, pointing them out. “They’ll crush me, they’ll beat me down, for standing up to their twisted mind-control.” The teachers were bearing down on me. I had seconds left: “I’m just one person, but if we all join together as one and choose to wake up, they won’t be able to stop us. Join me! Together as one! Rise up! Rise –”

Two strong pairs of arms took hold of my legs. Those arms brought me down while another pair grabbed me from behind. But I made sure that my mouth wasn’t covered so I could carry on with my address: “Look what they do to you if you resist! I’m just one person! But together we can do it! Liberate yourselves! Set yourselves free from these controlling stooges! It’s a conspiracy, I tell you!” I wriggled, I writhed, I wrestled, I bit a constraining hand and writhe in their grips, but to no avail. “You don’t have to be trapped! You don’t have to live like this! You can be free!” Something thudded against my feet, then the double doors swung open and the teachers at last succeeded in getting me out of the exam hall. I could hear the lady invigilator behind me commanding the other students, “Get on with your papers. You will be given extra time for the disturbance.”

They carried me down a corridor and around a corner. I had stopped shouting by now, my audience taken from me, and I was no longer even resisting their restraint. Determinism had me back in its clutches.

When my captors realised this, they sat me down in a chair in the foyer and ‘examined’ me. My old Physics teacher and one time form tutor, Mr Brownwood, led the interrogation: “Buckland, what’s got into you? You’ve been doing so well. You haven’t had an outburst like this in years.”

“I’m sorry sir. I don’t know what happened. I suppose it’s just the pressure of it all.”

Behind Brownwood I could hear the invigilator with the now bloody nose asking Mr Floss, my Philosophy teacher, “Happened before, has it?”

“Not for a long time – in school at least. We thought he was fairly stable.”

As Brownwood continued to ask me questions and I continued to answer them in imitation of a compliant robot, I considered my options. These people – the representatives of unfreedom, coercion, and doing that which everyone expects you to do because it is ‘the thing that must be done’ – were going to assess me as to whether they thought it was safe to return me to the exam hall or not. If so, then I would go back in and finish the exam, though I wasn’t sure if I could get the grade I wanted in my current state. If not, then I would be forced to resit the exam a later date – and so also take a gap year, delaying my progress to university, where I could continue my quest to solve the problem of freedom and determinism.

I didn’t like those options. Why should they be the only ones available to me?

This really was a test. It was an exam from the Universe to see whether, confronted by the forces of determinism and the opportunity to take hold of my own freedom, I would choose correctly. I already knew what I was going to do: I was going to exert my freedom. I was going to make my own, new options.

“So,” said Brownwood in conclusion, “do you feel up to going back in there and having another go, Buckland – without any outbursts this time? Do you think you could manage that?” It helped that the school was fixated on obtaining good exam results.

“Yes, I think so, sir,” I said. “But… could I please go to the toilet first?”

There was some reluctance about this, but in the end I was escorted by Brownwood and Floss to the nearest bathroom as my other captors dispersed. As I went inside, the two teachers stood on either side of the door like two bouncers at the entrance to a night club, completely over-exaggerating the situation.

This was my moment of opportunity. They would be least expecting me to suddenly emerge when I had only just gone inside. So as soon as the door swung in after me, I then ran back through it again.

“Hey!” Floss shouted.

“Buckland, come back here!’’ shouted Brownwood, ‘‘Oh, not again!”

The other teachers had by now made it back to their respective classrooms, so Brownwood and Floss had no reinforcements readily available, and I had the jump on them, putting them at a severe disadvantage.

Of course, they could have just let me go. But I wasn’t planning anything so simple as running away from school, this time. This time, I had a larger goal in mind. When I had put a few breathless paces between myself and them, and had rounded a corner out of their sight, I darted through the nearest classroom door.

Inside was a Third Form Spanish lesson. For a gorgeous instance the boys just stared at me in shock, wondering what was happening – as did Miss Valencia. Then I shouted “It’s time to leave school, boys! Break free from the chains of oppression! Choose to decide your own destiny, for a change! Anyone who wants to be free, come with me! Get out now while you still can!” and other similar slogans of liberation.

Miss Valencia gave me the most deathly gaze I had ever yet encountered in my short life. Some of the boys smiled at me. Some of them looked confused or scared. But a couple of the brave ones got up out of their chairs.

“Stay right where you are!” Miss Valencia bellowed at them. “Pay no attention to this foolish young man!”

“Don’t listen to her!” I said. “You can be free, if you choose to be!”

I sprang out of the door, ran a bit further, then picked another classroom. I was in the Modern Languages block, so this time it was Upper-Fourth form French. I did a lap of the room, shouting my plan of liberation and pulling some of the boys up out of their chairs.

When I returned to the corridor, I was pleased to see that some of the Spanish students had made it out, and were now either following me, or making a break for the school exit. What strength of character! All it took was one person to light the touch-paper, and a revolution could be started. The teachers would be powerless against the full force of the combined student body. All the students needed to do was to realise this.

I ran into more classrooms, proclaiming my gospel of freedom. And whenever a classroom had a door to another room or to a different corridor, I took it, trying to keep Brownwood and Floss off my trail. In each room I composed a new slogan and added it to my litany of invitations:

“Become who you were meant to be!”

“Exert your own autonomy!”

“Live dangerously!”

Some teachers did come after me, but it was difficult for them to reach me because by now the corridors had started filling up with revolutionaries and curious observers. I had plunged the school into chaos! Sweet, anarchic, equalising chaos, from which the ferment of freedom could be wrought! A tidal wave of students, teachers, classroom assistants and admin staff had now built up; but it was unstable, and kept changing course, shifting as more pupils actualised their free will and joined the fray. And I made sure that it remained unstable by taking an unpredictable route through the school.

After only a few minutes a familiar if furious voice came over the school tannoy: “Attention everyone. There has been a minor disturbance created by a troubled sixth former. Everyone is quite safe. On no account are students to leave their lessons. Return to your classrooms, and remain in them.”

Ha! A minor disturbance! Is that what they called this? I’ll give them ‘minor disturbance’, I thought.

By this point I had accumulated quite an entourage of accomplices, like a pied piper without any actual instrument, except for the instruments of my genius and charisma. I was going to set them free from the rat race.

“Where are we going?”

“What shall we do next?”

“Why are we doing this?” they squeaked.

“Just follow me!” I proclaimed. I judged that I had raided enough classrooms by now, so I charted a course for the playing fields.

People were shouting. The announcement over the speakers seemed to have had the reverse of its intended effect, and more teachers and pupils alike were emerging from classrooms just to see what was going on. And somewhere far behind us, Brownwood and Floss were still scrambling to catch up with me.

We broke out into the playing fields, and I led the revolutionaries to the school gates.

“What do we do now?” asked one boy – an Upper-Fourth former with spiked-up hair.

“Now?” I responded. “Now you do whatever you want! You choose what to do, of your own free will! You’re no longer subject to the deterministic laws of society!”

“But, won’t we get in trouble?” asked another boy, a Third Former with a face hidden somewhere behind his acne.

“Trouble? Who cares! You were in far worse trouble just blindly going along with the laws of society! Get out while you can!”

But this only elicited a chorus of doubts:

“I don’t know if that’s such a good idea…”

“My parents won’t be very pleased if I leave school…”

“Won’t the police come and catch us if we run away…?”

Realisation dawned on me. These boys hadn’t really been joining me in the revolution at all. They hadn’t had their hearts and minds captured by the ideal of freedom. They had only been playing along with me, as if it were just a big, foolish prank that they were playing on the teachers temporarily, but which they would soon abandon to return to their fatal, quotidian mediocrity. When it came down to it, none of them had the courage to step outside of the parameters of their society, of their school, of the chemicals in their brain, of any form of determinism. When it came to it, none of them had the courage to become independent, to think for themselves, to actualise their own free will.

The teachers were closing in on us. I made one last-ditch attempt to enlighten them: “I don’t believe you! You’re all so close to freedom – and yet so far! But who’s brave enough to take the first step? It might be the best – and the first – decision you ever make! Come on! When was the last time one of you chose to do something you actually wanted to –” I was cut off at this point because Mr Brownwood tackled me to the ground. He really was a very dedicated teacher.

In due course, my father was telephoned, along with, as usual, the police.

I was going to have to take a gap year after all, I reflected, as I sat in the Headmaster’s office, waiting for my future to be determined.

© Dr Luke Tarassenko 2023

Luke Tarassenko is a secondary school Philosophy teacher with a DPhil from Oxford on the work of Kierkegaard.

• This story has been adapted from Luke’s novel about free will, Breaking Free, available from Amazon as a paperback or ebook (search for ‘Breaking Free Tarassenko’).