Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Urgency of Art

Sam McAuliffe thinks that art offers another way of thinking.

Today science is widely regarded as the bastion of truth and knowledge. Technology daily demonstrates the truth of science to the person in the street, religion is ever trying to align scientific insight with its doctrines, and we largely expect our politicians to consider and abide by scientific evidence. No matter how rigorous or robust the science is, however, it fails to incite the social change it spotlights as needed, climate change being the obvious example. Moreover, some very influential philosophers equate science and technology with thoughtlessness. Could they be right? And if so, could art offer an antidote?

The political theorist Hannah Arendt summarised the problem best in The Human Condition (1958), when she wrote:

“The reason why it may be wise to distrust the political judgment of scientists qua scientists is not primarily their lack of ‘character’ – that they did not refuse to develop atomic weapons – or their naïvete – that they did not understand that once these weapons were developed they would be the last to be consulted about their use – but precisely the fact that they move in a world where speech has lost its power” (p.4).

This provocative passage by Arendt suggests two important insights. First, she highlights the limits of science, or at least, of scientists. Similar to the atomic scientists of the 1940s being incapable of controlling how the product of their labour would be deployed, contemporary scientists are incapable of catalysing the necessary social change on urgent issues such as climate change and warfare. (This isn’t a personal criticism, for strictly speaking it’s not their job to do so.)

Second, Arendt highlights the distinction between knowledge and thought. Scientific knowledge, the great triumph of the scientific method, is expressed in equations and data, inaccessible to those without mathematical skills and is thus distinct from speech and discussion. Even as the power of the word slips away we become enraptured by the progress of science and technology, yet unable to think beyond the gadget in front of us.

Arendt is not the only philosopher to speak of our ‘thoughtlessness’ in relation to science. Her former lover Martin Heidegger wrote extensively about technology and society. In his essay Discourse on Thinking (1959), he claimed that we’re living in a thoughtless time: “Thoughtlessness is an uncanny visitor who comes and goes everywhere in today’s world. For nowadays we take in everything in the quickest and cheapest way, only to forget it just as quickly.”

We turn to science to cure cancer, improve crop yield, harness energy, design our bombs, and understand the laws of physics – so why is it that some of our greatest thinkers have drawn a connection between science/technology and thoughtlessness? And if they’re correct to do so, what can we do about it?

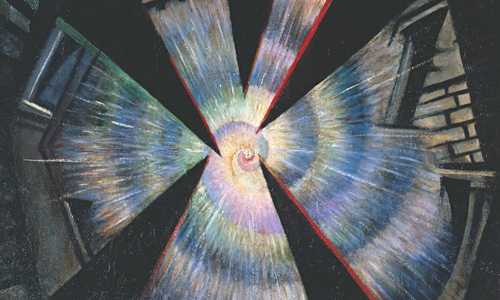

Bursting Shell Christopher Nevinson 1915

The Limits of Science

In his book The Gay Science (1882) Nietzsche famously claimed that “God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him!” (p.120). However, we must remember that Nietzsche is lamenting the death of God not celebrating it. God was once the pillar of truth and morality, and as long as we followed the word of God, we could rest easy knowing we were on the right path. But as various voices called the word of God (that is, the Bible) into disrepute from the eighteenth century onwards, the stable footing that monotheistic religion offered the West crumbled away. We Westerners were left perplexed. If not to God, where do we now turn for knowledge and moral guidance?

Many would say that science has been passed this baton. So we must understand the limits of science. For instance, science has almost nothing to say about ethics, and can teach us little about politics. So if we concern ourselves only with that which falls under the banner of ‘scientific method’, we necessarily narrow the questions we ask and the answers we seek, and ultimately we will fail the basic task of humanity, surviving together. Indeed, we are no better at getting along now than we were before the scientific revolution; we’re just a lot more powerful in what we can do.

Even if we accept that science cannot answer our existential predicament, we should still address the fact that both Heidegger and Arendt equate science and technology with thoughtlessness. A popular anti-religion argument says that science moves ever onward and constantly seeks development, whereas religion is dogmatic. However, although fixed thinking may get us nowhere fast, riding the wave of science and technology leaves us no time for contemplation. The pace of progress leaves us no time to think. As Heidegger says, ‘we forget to ponder’.

Lessons From Art

Given God’s receding (or ‘death’), and the fact that science is limited in what it can achieve, where should we turn? What will guide us back onto the path of thoughtfulness?

Some leading contemporary philosophers, such as Günter Figal, Santiago Zabala, and Jennifer McMahon, suggest that art offers the necessary path to salvation, since art is a site of intervention and interpretation. Far from merely pretty paintings or catchy melodies, and so being of peripheral concern to our contemporary predicaments, art offers engagement.

Art does not have to be ‘agreeable’: pretty or catchy, etc. Art can be agreeable; but it can also be ugly, weird, or banal. The defining characteristics of art are instead that it is perceived by the senses, and that it challenges us to understand the world differently. When we engage with art, we step out of the bubble that social media and our other experiences have created around us; we put our prior expectations to one side; and truly try to understand the artwork before us. A work of art is never what we want it to be – it is independent of the meaning we project upon it. To understand a work of art, we must attempt to receive what it is trying to say. And so in aesthetic contemplation, for that moment, however long it lasts, we are spurred to thoughtfulness.

Art appreciation is perhaps not a mode of thinking we readily equate with ‘thinking’, especially given the extent to which we are conditioned to technological modes of thought. Aesthetic contemplation is not the solving of a puzzle or problem: it is not the application of the right formula or theory to reach a desired outcome. Rather, it is being ‘caught up in’ or ‘taken up by’ that which is before us, and allowing that experience to transform us in some way. Contemplating art is not a mode of thinking that attempts to dominate or control its subject. Instead, it is a mode of thinking where one converses with a subject, or participates in the experience. It is a mode of thinking where one simultaneously arrives at an understanding of the subject and oneself. Through good art we learn how the world might be understood differently to how we understood it before. Engaging with art thus illuminates new or different ways to think, do, and be; and so it broadens our horizons. And each such engagement makes us more comfortable with this participatory mode of thought. In this way, art offers lessons in a mode of thoughtfulness distinct from the scientific method.

Of course, the thinking described here should not replace scientific thought. It should complement it. Yet it is only when we recognise distinct modes of thinking and understand how they fit together and what they can offer one another that we reach a certain cognitive balance. Considering the current state of the world, it is clear we have lost this equilibrium. Indeed, it is questionable whether such balance has ever been achieved. But striving toward balance in thought is our constant task.

The contemporary urgency of art is that it teaches us to engage with the world in vital ways many of us have forgotten, overlooked, or ignored. Whatever your passion – music, dance, sculpture, poetry, architecture – do yourself and the world a favour, and take a lesson or two in thinking from art.

© Sam McAuliffe 2023

Sam McAuliffe is Dean of Studies and Careers at Mannix College, Monash University. He is the author of Improvisation in Music and Philosophical Hermeneutics, and numerous scholarly essays.