Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Interview

Brian Leiter

Brian Leiter is Karl N. Llewellyn Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Chicago, and founder and Director of Chicago’s Center for Law, Philosophy & Human Values. Angela Tan chatted with him about Nietzsche.

In the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, you wrote that Friedrich Nietzsche [1844-1900] aims at freeing higher human beings from their false consciousness about morality. Can you give us an example of this false consciousness which has been assimilated by our society?

There’s a very high value placed on being altruistic: taking account of other people’s interests and looking out for others.

Leiter © University of Chicago 2012 Creative Commons 3

Now Nietzsche is not a fool. He understands that a lot of people who talk about altruism aren’t altruistic at all. As he says about the German political leaders of his day, he finds it unbelievable that they can go to church every Sunday and take communion, because they’re the most unChristian people on the face of the earth. So the appearance is not the point. The point is that a high value is set on altruism, while any sign of pure self-concern is kind of disparaged. I think Nietzsche’s correct here. It’s a pretty common moral stance, even when people don’t actually act on it. People who are not altruistic will rarely own up to being selfish.

Trump is a good example of what Nietzsche would call ‘the selfishness of the sick’. Nietzsche wasn’t interested in promoting that kind of selfishness. Nietzsche’s point was about someone like Beethoven. If Beethoven had really taken Christian morality seriously – had really been an altruist and really concerned for the well-being of others – he never would have been Beethoven, because, if you read about Beethoven’s life, you learn he was completely self-absorbed – not in the pathetic Trump way, but in the sense that everything about his life was organized around ‘What do I need in order to write the next piece of music?’. He used everyone around him as an instrument for the purpose of creating the space and the time in which he could keep composing. That’s what Nietzsche calls ‘severe self-love’. So you might say, Nietzsche’s worry is that if you grew up thinking altruism is the most important thing and that suffering is terrible and always has to be alleviated, you’re not going to be Beethoven. Beethoven suffered unbelievably. It’s hard to imagine a crueller fate for a composer than to lose your hearing.

Beethoven was not altruistic; he was not concerned with the well-being of other people. He practiced a kind of severe self-love for the sake of his art. So Nietzsche worries that the next Beethoven – the nascent Beethoven that’s out there somewhere – will take Christian morality so seriously that they’ll end up spending their time trying to alleviate suffering rather than cultivating their talent for music. That’s roughly, I think, what Nietzsche has in mind with what I’m characterizing as ‘false consciousness’. And I think it’s fair to say that Beethoven’s music made the world a better place, or as Nietzsche would say, has helped make life worth living.

Actually, my favourite performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is from Japan, where they performed it with a chorus of 10,000 singers! Beethoven’s music is a kind of universal language. That was part of his gift.

How has studying ethics through both a philosophical and legal lens affected the way you make decisions, and informed your judgments?

There are two kinds of questions philosophers investigate about morality. Firstly, when we make moral judgments, are they objectively true or are they merely subjective? The other type of question moral philosophers try to answer is about whether a systematic moral theory can help you think about ethics. So in the modern era – say since Jeremy Bentham [1748-1832] – many philosophers have been attracted to utilitarianism, which says the right thing to do is whatever will produce the most utility for people. For Bentham, that meant you wanted to maximize pleasure and minimize pain for the most people. Other philosophers have developed a sort of systematic ethics following Immanuel Kant [1724-1804], which is an anti-utilitarian view, according to which the morally right thing to do gets different formulations based on intention: act for the right kind of reason; or act for the right kind of motive; or act out of respect for the moral law – where the moral law was supposed to be a law that any rational person would arrive at. So you have both meta-ethics and normative ethics.

I’ve studied both. I have a certain view of meta-ethics, which influences how I think about it all. I don’t think any systematic normative ethics is rationally defensible. All moral systems proceed ultimately from some premise that itself can’t be derived rationally from other premises. Rather, moral systems rest at bottom on powerful emotional inclinations we have, and that is the starting point for all normative ethics. So that’s a kind of meta-ethical view that informs how I think about ethics. I also happen to think that both Kantian and utilitarian ethics articulate aspects of ‘common sense’ Western morality, at least among the bourgeois classes from which most philosophy professors come.

Beethoven: A higher man

Beethoven by Joseph Mähler 1804-1805

From Nietzsche I take the important point that people’s basic evaluative and moral commitments arise from emotional responses that we’re often trained to have from when we’re very young. In that sense, moral judgments don’t rest on a rational foundation.

Then there are interesting questions you can raise about what happens when you’re dealing with people whose fundamental moral commitments – which is to say, their fundamental emotional commitments – are completely different from yours. At that point, we’ve left what the philosopher Wilfrid Sellars calls the ‘Space of Reasons’. We’re out of the space where rational argument is possible, and we instead face conflict or mutual incomprehension over basic attitudes.

Nietzsche was very sensitive to this because he had spent his academic career studying ancient Greece and Rome. What he realized immediately when studying Greek and Roman literature and philosophy is that they don’t have a Christian morality. They aren’t utilitarians, and they certainly aren’t Kantians either. This really brought it home to Nietzsche that Christianity, and the moral philosophies that grew out of it – including Kantianism and utilitarianism, in different ways – were new inventions, new historical developments, very different from earlier ways of evaluating people and the world.

What would Nietzsche think of how knowledge is cultivated and the values which children are taught in modern school systems?

The modern educational system in the United States, to the extent that it involves moral education, is basically inculcating Judeo-Christian morality. Nietzsche was opposed to that: as he said, “herd morality is for the herd, but not for higher human beings.” Moral education tends to act as though there’s only one kind of morality possible; but again, Nietzsche, as a student of Greek and Roman culture, was well aware that the Greeks and the Romans had a completely different value system.

On the other hand, Nietzsche himself was a product of a modern research university system – a system which was created in Germany in the early nineteenth century by Wilhelm von Humboldt. In this version of the university, the university is the place where the only things that are taught are sciences – which is Wissenschaften in German. But Wissenschaft doesn’t mean ‘natural science’, but rather, any scholarly discipline. So Nietzsche was trained in classics, which was a Wissenschaft. It means there were certain skills and methods he had to use in order to acquire reliable knowledge about the ancient world. Nietzsche had Latin and Greek, and read a number of European languages. But he also had to know how to analyze ancient texts to evaluate their authenticity and how certain words or concepts were used across different texts and different authors, to establish their meanings. He was trained in the science of classical philology, which is what they called classics throughout his life. He had a great deal of respect for the men of Wissenschaft, and especially his teacher, Friedrich Ritschl, who was a great German classicist.

But he also thought that the problem with these great men of science, these scholars, is they had discipline, they acquired knowledge, but they didn’t ask, ‘Why do we want this knowledge?’ And they didn’t answer the relation question, of what’s valuable: “What’s it all for?” That’s why early on in his career Nietzsche broke from classical philology, even though he was a very well-trained and very good nineteenth century classicist. He wanted to put that training to a different use. He broke away pretty quickly from the mainstream of the academy because what he was concerned with the question of what was valuable.

What Nietzsche took away from the study of Greek [theatrical] tragedy in his first book The Birth of Tragedy (1872), is that there’s an important lesson in it for our own culture. The Birth of Tragedy was an extremely polemical book that was unlike the typical piece of scholarship, and it kind of destroyed his reputation among traditional scholars. But the book was dedicated to the composer Richard Wagner [1813-1883], who thought it was wonderful, since it was about a matter close to his own heart: the rejuvenation of culture. ‘Why was fifth-century Greek tragedy so great? And what can we learn from it?’ Well, that’s a simplified way of putting the topic of The Birth of Tragedy.

Now I don’t think Nietzsche thought you could educate people for the purpose of asking his questions. I think, as I said, he had a lot of respect for the universities as places that teach scientific disciplines, as long as we remember that for him ‘scientific’ is a very broad term. It includes history, it includes philosophy, and the study of literature and art, as well as the natural and human sciences.

How do you think Nietzsche would critique contemporary consumer culture in the twenty-first century?

I think Nietzsche was already worried in the late nineteenth century about the effects of capitalist materialism. He was already worried that European culture and society were becoming trivialized, and that people were becoming, as he called them in Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883), the ‘Last Men’ (Letzte Menschen) – only interested in bourgeois comforts and happiness, with no great aspirations, greatness, or willingness to undertake tasks that are too demanding.

I think this whole assessment applies even more now than it did back then. I also think Nietzsche didn’t understand, as, say, Karl Marx did, the way in which capitalism and capitalist markets permeate all aspects of life and culture. How do we know an artist is great now? Well, because their painting was auctioned for $50 million! That’s how we know it’s a great artist – and that was foreign not only to Marx’s way of thinking but to Nietzsche’s as well. So I’d say that Nietzsche would look around and say, “The Last Man has won, and our culture, and the potentiality of our culture, is the worse for it.”

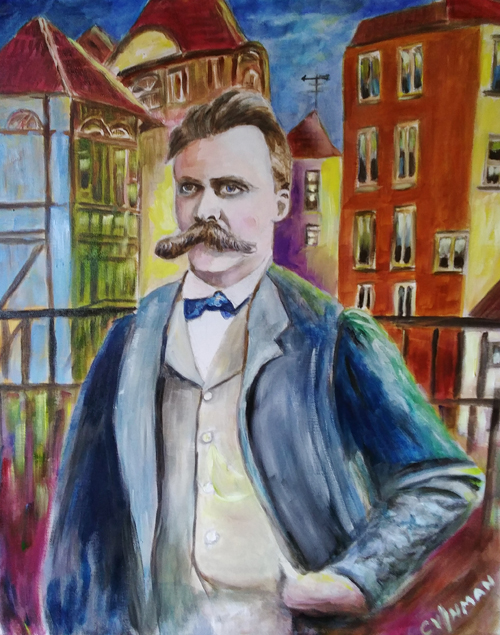

Friedrich Nietzsche by Clint Inman

© Clinton Inman 2024 Facebook at clinton.inma

Are there any specific aspects of Nietzsche’s work that had a lasting impact on your moral philosophy or outlook on life?

I think probably the biggest impact Nietzsche had on me, is that he persuaded me that everyone has certain essential traits of character that really don’t change very much over their lives, and that people having very limited ability to change themselves ought to have a lot of bearing on how much you want to treat them as blameworthy for the bad things they do, and whether we want to temper praise and blame a little. The analogy I use to capture this idea – which Nietzsche also finds in Schopenhauer – is that if you plant a tomato seed you’re going to get a tomato plant; you’re not going to get an oak tree or an apple tree. Of course, the quality of the tomato plant will be affected by various things – whether there’s enough sunlight or enough water – so there are things you can do to nudge the outcome. But fundamentally, it’s a tomato plant, and you will not get anything other than a tomato from it. People are like that too, in that people’s fundamental character doesn’t change very much throughout their life. It’s good to realize that, and yet not be resigned in the face of that. I always cringe a little when people say so and so is ‘evil’. Nietzsche was against that. He said we should be beyond good and evil. Calling people ‘evil’ presupposes something about their capacity to choose that I think probably isn’t right. The people that get called evil may be horrible, and you may want to keep your distance from them, but it’s not like they chose to be that way. That’s a fundamental truth about human beings which Nietzsche does press quite a lot. It certainly affected the way I think about lots of things, from myself to my children.

What publications or research are you working on now?

The main one, which is not too far removed from what we’re talking about, is finishing a co-authored book with a former PhD student of mine on Marx, which will be published soon. It’s meant to be a high-level philosophical introduction to the thought of Marx. But after that, I may actually turn to a more Nietzschean project, about the question, ‘Why is life worth living?’

• Angela Tan is a student at York House School in Vancouver interested in the intersection of ethics and education. As a host of the oxfordpublicphilosophy.com podcast, she hopes to bridge polarization through dialogue.

• Brian Leiter, in addition to his academic posts at the University of Chicago, has been a visiting professor at Yale and Oxford. He is very influential in philosophy of law, and his scholarly writings have concerned Continental philosophy, Marx and Nietzsche. A review in The Journal of Nietzsche Studies described Leiter’s 2002 book Nietzsche on Morality as “arguably the most important book on Nietzsche’s philosophy in the past twenty years.” He also runs The Leiter Reports, a widely read blog about academic phlosophy: leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/.