Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Books

Anti-Education by Friedrich Nietzsche

Daniel Telech reviews Nietzsche’s startling opinions on the aims of education.

In 1872, the same year that witnessed the publication of his first book The Birth of Tragedy, a twenty-seven year old Friedrich Nietzsche gave a series of five public lectures on the aims of education at Basel’s city museum. The aspiration of these lectures was to expose some corrosive tendencies he saw in German educational institutions, and more importantly, to chart a new direction worthy of such institutions.

In addition to constituting a valuable source for Nietzsche’s early views on culture, the lectures are notable for their experimental style. Nietzsche’s view is presented largely in the form of a fictionalized autobiographical dialogue that he reports as having overheard while a student. Contributing to the mythic quality of the conversation is its taking place in the woods, where Nietzsche and his friends have ventured for a pilgrimage of self-cultivation. Although layered, and replete with literary, historical, and political references – which editors Paul Reitter and Chad Wellmon usefully uncover in the endnotes – the reader approaching this text expecting the literary mastery of a Ciceronian or Humean dialogue may encounter disappointment. Still, the lectures might be well viewed as a rehearsal for the philosophical-literary achievement that is Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

The Death of Classicism

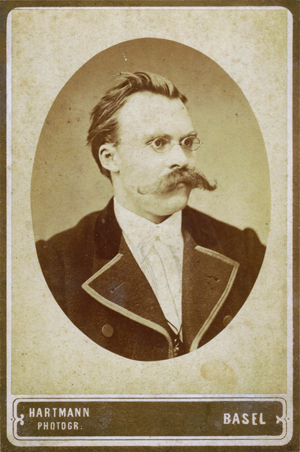

Photograph of Friedrich Nietzsche in 1872, the year he gave his public lectures on education.

The target of Nietzsche’s censure is a pair of tendencies: “One is the drive to expand education as much as possible… to extend education and culture to an ever wider circle”; the second “is the drive to narrow and weaken it… [which] expects education to give up its highest claim to autonomy and submit to serve another form of life, the state.”

Although it would be a mistake to see Nietzsche as a champion of either liberalism or democracy, his objection to educational expansion is not that higher learning must be reserved for the select few. Rather, Nietzsche objects to the ‘national economic doctrine’ guiding the expansion. This economic doctrine sees higher education as being training for state service, and generally as a means to economic growth. An upshot of this tendency is the growing demand for “a rapid education, so that you can start earning money quickly… Culture is tolerated only insofar as it serves the cause of earning money.” So Nietzsche’s chief objection to educational expansionism is its rendering the school a mere pit stop for fashioning au courant professionals.

For Nietzsche there’s nothing offensive per se in wealth acquisition. But Bildung – education in the true sense – is partly a process of self-cultivation, aimed at the forging of ‘true culture’ within oneself (Damion Searls’ translation, it is worth noting, tracks well the various senses that concepts rich in meaning such as ‘Bildung’ can express). Yet self-cultivation, Nietzsche laments, is blocked when the institution responsible for its promotion “reduces scholars to being mere slaves of academic disciplines.”

A by-product of this ‘weakening’ is that great stock is placed on academic hyperspecialization. Almost a hundred years earlier, Adam Smith optimistically anticipated the division of labor to be an engine of economic growth. Nietzsche recognizes the truth in Smith’s prediction, but “A scholar with a rarefied speciality is like a factory worker who spends his entire life doing nothing but making a single screw, or a handle for a given tool or machine.” Single-mindedness of this sort rarely instigates a process of self-cultivation. And yet, on the production line of the modern university, hyperspecialization presents itself as an academic virtue.

What real alternative, however, can there be to hyperspecialization? Dabblers beware, dilettantism is for Nietzsche no ideal. Expressing his disdain for laisser aller [‘letting go’], in Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche claims that “The essential thing ‘in heaven and on earth’, so it appears, is, to make the point again, that there is obedience for a long time and in one direction: in the process there comes and always has come eventually something for whose sake living on earth is worthwhile.”

But if neither hyperspecialization nor dilettantism, then what? In response Nietzsche focuses on the gymnasium, the academically-oriented and selective German secondary school that Nietzsche takes to set the standard for all other German educational institutions. Nietzsche maintains that the gymnasium must strengthen its emphasis on classical education. Young scholars, Nietzsche laments, lack reverence for Hellenistic culture.

Culture Above All

In addition to the neoclassicist imperative to breathe in the artistic and literary styles of Ancient Greece and Rome, Nietzsche insists that students take greater care of the German language: “Take your language seriously! If you cannot feel a sacred duty here, then you have not even the seed of higher culture within you.” Nietzsche’s literary experimentalism is difficult to square with his expressions of linguistic conservatism, one example of which is his hostility to what he deems the vulgarizing influence of journalism. In fact, Nietzsche holds that the two pernicious drives expanding and weakening education meet in journalism. Echoing Kierkegaard, who wrote that “the daily press is the evil principle of the modern world,” Nietzsche claims that “the daily newspaper has effectively replaced education, and anyone who lays claim to culture or education, even a scholar, typically relies on a sticky layer of journalism.”

Tedious though it is to insist that a return to the past is not what some thinker demands, it is striking to read Nietzsche’s disparaging words about times that fostered great figures such as Goethe and Lessing. Although Nietzsche mourns the absence of contemporaries like these, their cultural environments too were mired with obtuseness. Speaking as if German culture were on trial, Nietzsche issues the following indictments: “Lessing, reduced to dust by your idiocy… Lessing, never once able to venture that eternal flight for which he had come into the world?… Not one of your great geniuses has ever received any assistance from you, and now you want to make it a dogma that none should receive any in the future?” Yet in spite of Nietzsche’s frustration with German culture, a sometimes unsettling nationalism resides in these lectures. There are numerous references to the need for a renewal of the ‘German spirit’, since “‘German culture’ today is a cosmopolitan composite” – one that Nietzsche construes as unduly influenced by the French.

Nietzschean Perspectives

Given the value that Nietzsche places on wide-scale cultural revision, one might expect him to exhibit greater hope in the potential of journalistic media. If culture is “above all, unity of artistic style in all the life expressions of a people,” then why not put popular writing in its service?

In characterizing Nietzsche’s opposition to ‘educational expansion’, I kept elitism out of the picture. However, there are limits to such charitable readings. Consider Nietzsche’s remarks in a section from Twilight of the Idols titled ‘What the Germans Lack’: “What contributes to the decline of German culture? That ‘higher education’ is no longer a privilege – the democratism of Bildung, which has become ‘common’ – too common.” So on the one hand we have a Nietzsche who argues that educational expansion is destructive because of its degradation of academic standards, and with it, the prospect of genuine self-cultivation; and on the other hand, certain of Nietzsche’s attitudes betray an elitism that extends beyond concern for pedagogical standards.

Perhaps this is to be explained away by his commitment to an outmoded picture of genius. Perhaps. But, supposing we have to choose between the first and second ‘Nietzsches’ (there might yet be others!), we can at least be confident that the first Nietzsche – the philosopher concerned with self-cultivation and cultural flourishing in its own right – is not an invention of ours. As readers of literature about Nietzsche will know, there are serious challenges in reconstructing his theory of value in a way that allows for education to be intrinsically valuable, and yet Nietzsche leaves little room for ambiguity when he claims that “The entire system of higher education in Germany has lost what matters most: the end as well as the means to the end. That education, that Bildung, is itself an end… that has been forgotten.”

Nietzsche’s concerns are timely. Humanistic education continues to be under attack, and avenues for ‘expansion’ and ‘weakening’ continue to proliferate. If we find in Anti-Education an ally in the fight against the instrumentalization of education, we might learn much from him.

© Daniel Telech 2016

Daniel is a PhD candidate in the Philosophy Department at the University of Chicago.

• Anti-Education: On the Future of Our Educational Institutions by Friedrich Nietzsche, trans. D. Searls, eds. P. Reitter & C. Wellmon, NYRB, 2015, $10 pb, 160 pages, ISBN: 978-1590178942