Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Is Brillo Box an Illustration?

Thomas E. Wartenberg uses Warhol’s work to illustrate his theory of illustration.

Recently I took part in an ‘Author Meets Critics’ session at the 2024 College Art Association Meetings. The three critics of my book, Thoughtful Images: Illustrating Philosophy Through Art (OUP, 2023), were all artists. Each had insightful things to say about the relationship between my claims about illustration and their own artistic production. I was genuinely touched to hear how my book had affected their understanding of their own work as well as how it shifted their previously dismissive attitude towards ‘mere’ illustration. But afterwards, during the question-answer session, a question arose that has been preoccupying me ever since.

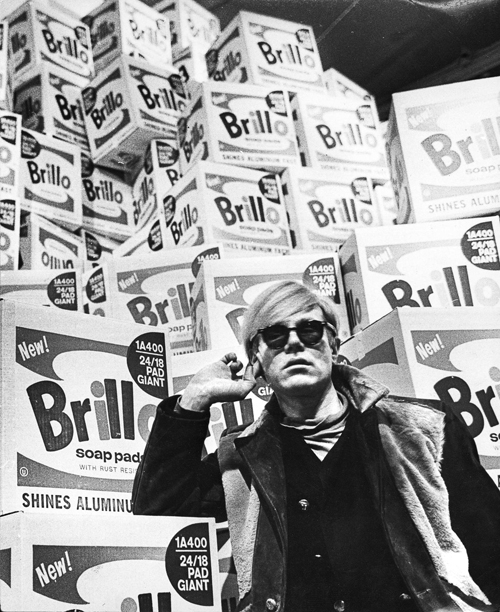

During my talk I had mentioned Andy Warhol’s famous 1964 artwork Brillo Soap Pads Box, aka Brillo Box. The work is a replica of the cardboard cartons containing boxes of Brillo soap pads you can buy from supermarkets. Warhol had numerous boxes fabricated out of plywood, and with the assistance of Gerard Malanga and Billy Linich, he then painted and silkscreened the boxes with the Brillo product logo and associated words and colors. The result looked almost identical to the standard cardboard cartons containing Brillo soap pads. The question I’ve been thinking about is: ‘Is Brillo Box an illustration?’ Despite having discussed the work both in my book and my response to the critics at the CAA session, I had not considered that specific question. I was surprised by it and did not have a good answer to it at the time. But I have continued to think about it, and, as a result, have modified some claims I made about illustration in Thoughtful Images.

Brillo Box Warhol photo by Johnzhouse 2021 Creative Commons 4

Illuminating Illustrations

To explain this, it will be helpful to provide a little background about the claims I made in Thoughtful Images about the nature of illustration.

The most fundamental feature of an illustration is its relationship to the source of which it is an illustration. One reason illustration has traditionally been denigrated in relationship to, say, painting, is that this dependency on a source has been taken to disqualify illustration from being real art. This is, I argue, a mistake – one that results from failing to understand that illustration is not a specific artform, like painting or sculpture, since works in any artistic medium can have the relationship to a source that constitutes an illustration.

I developed a classification of the different sources that illustrations can have. The most common form is one in which an illustration is derived from a written text. Everyone is familiar with this type of illustration. For instance, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) originally contained many lovely illustrations of Alice’s escapades that John Tenniel made based upon Carroll’s own drawings.

I also discuss two other types of illustrations that are particularly relevant to philosophy: concept-based and theory-based illustrations, where illustrations are based upon a philosophical concept or theory. These types of illustration are not as familiar to most people since the works are not as widely disseminated as text-based illustrations, but one of the best-known is the frontispiece to Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651). The etching was made by Abraham Bosse under the supervision of Hobbes, and provides a visual analogue to Hobbes’ theory that the power of the sovereign is based upon the consent of those he governs. It contains the figure of the sovereign towering over a landscape, but upon closer inspection, one sees that the body of the sovereign is made up of the bodies of his subjects.

Quotation-displaying illustrations are the final type I recognized in the book, though I used slightly different terminology there (in the book I called them ‘quotation-based illustrations’). Unsurprisingly, these consist of artworks that display quotations from texts. This type of illustration was first developed by conceptual artists in the 1960s, who made works that consisted of quotations from a text rendered in a variety of artistic mediums. The first such work I know of is Bruce Nauman’s A Rose Has No Teeth (1966). This consists of a lead cast that displays the phrase from Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations that forms its title. (You can find an explanation of what the quotation means in Chapter 7 of Thoughtful Images.)

There are two fundamental norms that govern illustration: fidelity and felicity. ‘Fidelity’ specifies that the work must be faithful to its source; ‘felicity’, that illustrating something in a given medium can allow for alterations to satisfy the needs of that medium. The two terms are derived from translation theory, but are also applicable to the translation of a text or idea into a visual medium rather than from one language into another.

Leviathan

Illustration Illustrations

Now we’re ready to answer the question of whether Brillo Box is an illustration. Since I claim that any artwork that’s derived from a source is an illustration, Brillo Box qualifies as one, as it has a clear source – the cardboard cartons of Brillo Soap Pad boxes in grocery stores at the time the work was created. It replicates the cardboard carton in a different medium – plywood boxes of the same dimensions as their source, painted and silkscreened to look indistinguishable from their source. This fact is central to the work’s meaning.

However, admitting that Brillo Box is an illustration requires me to grant the existence of a new type of illustration in addition to the ones I’ve already included in my typology. Brillo Box is not a text-based, concept-based, theory-based, or quotation-displaying illustration: it’s an object-based illustration – an illustration that presents its object visually. What’s unusual about this work is that it does not transform the object it illustrates, but replicates it.

Other artists followed Warhol’s example. Most notably, in 1960 Jasper Johns made two sculptures entitled Painted Bronze. Both works are cast in bronze but painted to make them indistinguishable from the objects they illustrate. In one case, Johns painted two Ballantine Ale cans. In the other, Johns painted a bronze cast of a Savarin Coffee can with paintbrushes in it, to look like something you’d see in an artist’s studio. Like Brillo Box, the Painted Bronzes are object-based illustrations. (I owe this example to William Conger.)

Reflecting on the category of object-based illustrations leads one to see that many artworks that are not currently recognized as illustrations should be considered such. An example is Peter Paul Rubens’ The Rape of Europa (1628-29). The work is derived from Titian’s similar work from 1562.

Titian

Once the work is categorized as an illustration, it makes sense to evaluate it in terms of the norms of fidelity and felicity. The role of the norm of fidelity is acknowledged in this description of the work by Rosily Roberts:

“Titian’s Rape of Europa is an erotically charged work consisting of soft, blurred lines and the use of bright but gentle colors. Rubens has brought all of these characteristics into his own version, mimicking, among other things, Titian’s off-centered composition, and the sense of dynamism and drama that underscores the whole work.”

(‘Rubens’s copies of old masters’, available online)

So in creating his painting, Rubens sought to remain faithful to many of Titian’s stylistic choices. But Rubens was not content to simply make a copy of the Titian painting. Rather, he used it to explore possibilities for his own work, following the dictates of the norm of felicity to alter features of the source, as Roberts points out:

“Rubens departed from Titian’s work in the rendering of the female body. Rubens used cool grey half-tints and emphasized the suppleness of Europa’s flesh, demonstrating his own approach to form and color.”

So Rubens’ work is not simply a copy of Titian’s. Treating it instead as an object-based illustration gets viewers to see the role of the norms of fidelity and felicity in it. This makes it apparent that felicity applies to changes in the target work that result from something other than a change of medium. At the same time that Rubens was adhering to the norm of fidelity to learn from Titian’s example, he was also following felicity to realize his own unique painting style, creating a work that had its own integrity.

Rubens

Why Illustrate?

Some might think that this use of the concept of ‘illustration’ strains its bounds. There are, they may maintain, paintings that are based on paintings by other painters that are not in any meaningful sense illustrations. Take Picasso’s Portrait of a Painter, after El Greco (1950). The work is based on El Greco’s Portrait of Jorge Manuel Theotocópuli (c.1597-1603). Although the structure of the painting is clearly derived from its source, Picasso’s use of his own characteristic style dominates the painting so fully that it could be maintained that it’s not useful to think of it as an illustration.

Without endorsing this view, I do acknowledge that it points to a limit in the applicability of the notion of illustration. When felicity becomes dominant over fidelity in a work, then even if the work is derived from a source, it makes no sense to view it as an illustration. Rather, illustrations are works derived from a source in which fidelity to the source is the dominant norm. But Brillo Box is such a faithful recreation of its source (albeit with different materials), that only the norm of fidelity applies to its relationship to its source. This immediately suggests a question: Why would someone create an artwork that replicates its source with near complete accuracy?

Paying attention to this issue points out that the framework for illustration I have so far articulated does not address the question of what the point of an illustration might be. I’ve simply categorized different types of illustration based upon their having distinct types of source. This says nothing about the significance of such works. But let’s take this opportunity to reflect on the ‘why’ of illustration.

Often, the reason for making an illustration is fairly evident. For instance, the manuscript illustrations in Nicole Oresme’s translations of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Politics are intended to make his theory of friendship more accessible to the courtiers of the French King Charles V. Because French lacked the words for many of Aristotle’s concepts, the illustrations provided important information to the members of the court about the meaning of those terms. Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting The Death of Socrates (1787) is a text-based illustration that provides a visual rendition of Plato’s description of Socrates’ death in his dialogue Phaedo. Portraying Socrates as facing his death with equanimity, David intended his viewers to take away the message that they should follow his example. Rubens clearly made his version of Titian’s painting both to learn from Titian and to develop his own style. But sometimes the motive for making an illustration is more difficult to determine. Picasso’s rationale for painting a version of El Greco’s portrait of his son is more difficult to determine, since Picasso had already developed his own painting style. Was he simply searching for a subject to paint? Did he think he might learn something from El Greco and the other Old Masters whose works he copied? We don’t know what his reason was.

Andy Warhol with Brillo Boxes Stockholm-1968 Public Domain

What then can we say about Warhol’s rationale for making Brillo Box? Why create a duplicate of an easily-available commercial product? Especially at the time of its creation, this work puzzled viewers. We can imagine them also wondering, ‘Why create an object that’s nearly visual identical to such an ordinary thing? What’s the point?’

Arthur Danto championed the work as making a significant philosophical point. Here is one version of how he put his claim:

“Brillo Box, in any of its many exemplars, made the form of that question [how is art possible?] finally and forever clear: how is it possible for something to be a work of art when something else, which resembles it to whatever degree of exactitude, is merely a thing, or an artifact, but not an artwork?”

(‘Andy Warhol’s Brillo Box’, Artforum, September 1993.)

This way of formulating the issue of the nature of art was novel; but after Brillo Box, the question of what makes something a work of art had to be asked differently. So the work changed the landscape of philosophical aesthetics. Brillo Box did this by making a philosophical point: by doing philosophy through art. So we might well say that Warhol’s reason for making this work was to illustrate a philosophical problem: How can one of two visually identical works be an artwork when its ordinary counterpart is not?

I continue to reflect upon illustration and to develop a theoretical framework for conceptualizing it. Brillo Box is an example of an artwork that has for me produced a more adequate idea of the notion of illustration.

© Prof. Thomas E. Wartenberg 2024

As well as Thoughtful Images, Thomas Wartenberg is the author of Thinking on Screen (Routledge) and other books. He is a Professor Emeritus of Philosophy at Mount Holyoke College, MA.