Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Philosopher Kings – & Queens?

Helene Scott-Fordsmand explores legitimacy in philosophy.

In 2020 a book by Rebecca Buxton and Lisa Whiting containing twenty portraits of female philosophers was published under the name The Philosopher Queens. It’s one among many recent books about an extensive diversity problem in philosophy, which includes issues of gender, body, language, culture, class, and ethnicity. Here I focus in part on gender.

The title of the aforementioned book is a pun on the concept of ‘philosopher kings’, which many readers may know from Plato’s Republic (c.375 BC). According to Socrates, who is Plato’s mouthpiece in the text, philosopher kings are the would-be administers of the ideal society, who, based on their philosophical understanding, can lead the people in a true and just way. Describing these ‘kings’, Socrates notes they may perfectly well be women, as the ideal society would have equality between the sexes. He adds that the idea of gender equality will likely seem much less controversial to his audience than the idea of a philosopher ruling class. The controversy then is about philosophers, not women. But who gets to count as a legitimate philosopher?

Who Can Be A Philosopher?

First, being a philosopher is an activity-based identity. Unlike actual kings and queens, you’re not born a philosopher. Nor is it an officially conferred title, such as knight, mayor, or doctor. You’re a philosopher because you do philosophy. The challenge here, though, is that the nature of philosophy, is itself a philosophical question, and therefore the subject of rich philosophical debate. Many philosophers might agree that philosophy is hard to define, but might say, ‘I know it when I see it’. Thus a loop emerges, where those who can already claim to be philosophers get to ‘know it when they see it’ and hence shape the boundaries of what philosophy is. In turn, what they call philosophy then serves to legitimize their own ‘philosopher’ identity.

While most people nowadays (though not all) agree with Plato that the role of philosopher should be credited from ability and not from gender, there is still a predominance of men amongst philosophers. You can see this on course curricula, in philosophy handbooks, at conferences, and in the press. There are many reasons for this. For example, relatively more women drop out of philosophy (and academia more broadly) during their studies and early in their careers for various gender-related reasons. In the past, the obligations of marriage meant that many educated women had to give up academic life. Today, caring responsibilities are still an obstacle for women’s careers more so than for men’s. Adding to this, it has been shown time and time again that a general bias in evaluation makes it harder for women to get philosophy jobs. This continuous alienation can cause self-silencing and underperformance. Part of the explanation, however, may also lie in how we view the women who actually do manage to pursue a thinking career.

Elisabeth of Bohemia by Gerard van Honthorst 1636

A well-known historical example of such a woman is Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618-1680). She was a key philosophical interlocutor for René Descartes (1596-1650). In correspondence between them, she challenged his dualism and urged Descartes to take the emotional aspects of human life more seriously – a topic she worked on and discussed with several intellectuals. Despite being an important figure for the philosophy of her time, who developed an interesting counterpoint to the Cartesian view of human nature, it briefly caused chaos and discontent among students at my old alma mater, the University of Copenhagen, when her texts were added to the History of Philosophy curriculum in 2018. Students feared that studying her would take away space from ‘real’ philosophers, and thus protested against this revision. And so we return to the question of what a real philosopher is.

One of the first things I was told when I started my philosophy degree, was that you don’t become a philosopher by studying philosophy, you became a philosophy professional (or fagfilosof in Danish). This, we were to understand, was a different matter. On the one hand, this awkward title is meant to protect serious academics from the ‘philosopher’ title to which anyone can lay claim. On the other hand, it signals that there’s a difference between philosophy graduates (us) and ‘real’ philosophers such as Plato, Kant, or Hegel. Again philosophy is characterized by canonical thinking, that is, demarcated by the identification of and engagement with the ‘real’ philosophers.

The construction of these canons – and the involved negotiations of belonging that goes with it – is a complex matter, and one which is historically and culturally sensitive. In the last century, names such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, Hannah Arendt, Thomas Kuhn, or Michel Foucault have been added into the canon. Other thinkers, such as Donna Haraway, known for her ‘Cyborg Manifesto’ (1985), Bruno Latour, known for his ‘actor-network theory’, and Julia Kristeva, perhaps best known for her work on the concept of ‘abjection’, have been placed merely as ‘canon adjacent’. Asking why this or that thinker is or is not included takes us into swampy territory, because the criteria are vague. Nevertheless, let me outline some elements that may have been at play when a thinker such as Foucault – who was interested in social history, and deliberately avoided the ‘philosopher’ title – is canonized, while thinkers such as Haraway and Kristeva – widely recognized for their original conceptual analyses – are not.

Disciplinary Boundary Work

The complex game of who to accept as a ‘real’ X (eg, philosopher), and the arguments for and against inclusion, are known in science studies as ‘disciplinary boundary work’ (a term ascribed to the sociologist Thomas F. Gieryn). Motivations for maintaining disciplinary boundaries are many and various. It can be about power relations and the struggle for prestigious appointments or funding; but it can also be about who can ‘legitimately’ speak as an expert on certain topics in public debates or in the media. Or it can be a pragmatic question about identifying appropriate peers for the ‘peer evaluation’ system, which is a cornerstone of academia. It involves explicit positive definitions of what a discipline is, and negative definitions of what it is not. Equally, it is influenced by previous examples of inclusion and exclusion. For example, if someone says ‘Richard Dawkins’ work on biologically-based atheism is not philosophy’ or indeed the opposite, then they are doing philosophy boundary work. To justify this, one might compare Dawkins to already-recognized examples of canonical philosophers, or point out that Dawkins’ questions about religion are or are not within the scope of classic topics in philosophy.

Academic disciplines are distinct for a variety of reasons of course. It may be that members of a discipline share a particular field of study (as with astrophysics); or a methodology (as with anthropology); or that the discipline is united by being rooted in a historical tradition (as with phenomenology). For example, Dan Zahavi has argued that much of what calls itself ‘phenomenology’ is not exactly that because it does not relate to the texts of Franz Brentano and Edmund Husserl, who founded phenomenology, and thus does not follow the historical legacy, which, for Zahavi defines the discipline. Whether one belongs to a particular discipline thus depends on how one relates to whichever particular aspect unites that discipline. As we have already learnt, what that is for philosophy remains disputed, and thus, justification must rely on comparison to already accepted inclusions rather than to explicit definitions.

Canons & Heretics

To know a discipline, you need some familiarity with its ‘canon’. This in turn provides a helpful baseline for professional discussion, since you can refer to commonly-known texts rather than explain everything from scratch. You can also make such discussions more concise by refering to very specific interpretations or ideas. In philosophy, for example, you might make clear whether you are using the term ‘existence’ in a Heideggerian or a predicate logical sense. Or you might refer to classic thought experiments – that are widely-known and discussed – scenarios that illuminate and challenge the problems with which philosophy grapples. In ethics, for example, there is the Trolley Problem; a drier example from epistemology is the Gettier Problem.

Readers less familiar with the philosophical canon may now be a little annoyed that I’m not going to elaborate here on what ‘existence’ means in a Heideggerian rather than a predicate logical sense, or what the Gettier Problem is. But this emphasizes the point: membership of an academic discipline depends on being acquainted with such references.

This kind of boundary work, where a group cultivates a shared understanding, through a shared conceptual apparatus and terminology, is sometimes critically referred to as ‘creating jargon’. This specifically entails the use of language as a marker of disciplinary affiliation, and thus as a mark of belonging. Jargon can indeed be an effective, quick way of communicating complex ideas precisely; but it also makes conversations difficult to enter, and indeed, is an effective way of excluding the uninitiated, or of dominating a discussion with junior colleagues, laymen, or scholars from other disciplines.

Beyond the upside of efficiency, and the downside of exclusion, there is a further challenge with drawing disciplinary frontiers through canonical jargon. It means that variation can be perceived as either irrelevant or heretical. Thus, when thinkers such as Haraway or Kristeva draw on their interdisciplinary background (Haraway with her roots in biology, Kristeva in linguistics) and reference literature and theories unknown to philosophers, or use atypical examples, their disciplinary affiliation may be questioned. More classically-trained philosophers may be struck by the absence of ‘classical’ philosophical jargon, and take it as a sign that the author is inexperienced in philosophy. Or they may not understand the examples given at first glance – perhaps they need to read up on biology – and therefore perceive the texts as ‘foreign’. Instead of being an opportunity for classically-trained philosophers to learn something new, the ‘newness’ of the texts becomes an opportunity for classically-trained philosophers to dismiss them. This, of course, is not related to gender, but goes for anyone operating in the fringes of the canon.

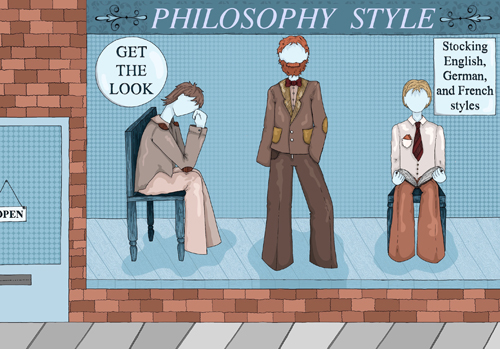

Image © Sylvie Reed 2024

When The Queen Has A Body

According to some, philosophy is a metascience, exploring how science can give us knowledge.

In this role, it is claimed that philosophy is the ‘queen of the sciences’. This phrase comes from Immanuel Kant’s Preface to his Critique of Pure Reason (1781) – “There was a time when she was queen of all sciences” – but is reproduced in many philosophical texts. Philosophy is queen (or king, for that matter) because its royal gaze, like the divine gaze, is above mundane life. Indeed, for Plato, the philosopher king should be rid of material property and simply live for the philosophical ideal and the good of society. Philosophy, as the queen of the sciences, similarly cannot be bogged down in wordly complications. As Descartes claims in his Meditations (1641), philosophy must start with absolutely pure – that is, certain – thought, so that it can be the foundation for everything else.

This kind of philosophical self-view yields a philosophy that wants to free itself from the world and from empirical conditioning. It’s present in Descartes’ cogito, Kant’s obsession with the a priori, and in Husserl’s epoché (an attempt to start philosophical analysis by ‘bracketing’ all preconceptions). Here, philosophical theories must stand above time and culture. If we fall into the culturally specific or historical, we leave philosophy behind and move into the empirical sciences – anthropology, history and the like. Even philosophers who draw on historical examples, like Kuhn or Foucault, aim for structures that are above their examples (concerning paradigms or epistemes respectively).

It’s worth mentioning that a less arrogant version of this can be found in the work of Mary Midgley (1919-2018), who considers philosophy not as monarch, but as a cartographer of thought; not ruling, but still elevated above other disciplines, maintaining an overview. Nonetheless, a supra-worldly, supra-temporal and disembodied interest is presupposed in either metaphor.

The philosopher must be above history, above culture, and most of all, above the unruliness of the body, in order to be crowned. ‘Real’ philosophy queens don’t get overwhelmed by grief; and they don’t have uncontrollable period pains (or at least, they don’t talk about it). However, for thinkers such as Haraway and Kristeva, it is precisely the situated – the relational and emotional, the corporeal and the unruly – which is crucial. This is not because they cannot think beyond it, but precisely as a philosophical point: knowledge is situated. Humans are bodies – and not just ‘nice’ bodies, but screaming, bleeding, dying, sweating, and, not least, born and birthing bodies. Unfortunately, attempting to break philosophy’s obliviousness of the body and emotional life excludes people who think this way from the ‘royal’ philosophical position.

Legitimacy, Authority & Change

How does this relate to the gender imbalance in philosophy? In Women in Philosophy: What needs to change? (2013), Katrina Hutchison writes that the dearth of women philosophers – in the literature, at conferences, and in the media – may be partly due to the way we judge expert credibility. Studies from psychology and sociology show that in contexts where we do not have professional expertise, our willingness to attribute authority is strongly influenced by bias. Partly, there is second-order bias, since bias already plays a role in assigning structural credibility through academic positions and publications; but there is also a primary bias at play, because the assessment we make will not only draw on institutional indicators, but also on whether the person falls within a group we consider to be credible. For example, if we usually see men in blue shirts as credible witnesses when it comes to economics, we might attribute less credibility to a man in a Hawaiian shirt (Why he is wearing that shirt? Does he not know the norms? Does he even know the field?). The same applies if we’re used to a certain gender, a certain skin colour, or a certain accent (Can someone with a cockney accent really tell me about nature?). In such situations we are more likely to ask for evidence of their expertise: “show me that my prejudices are wrong so that I can trust your statements.” This generates a ‘culture of justification’, in which minorities often find themselves asked to justify why they can be considered philosophers (or even academics) – through, for instance, canon, jargon, or ‘a royal gaze’.

In the West, the standard philosopher is a white, English-speaking (or perhaps German- or French-speaking), man – perhaps not in a blue shirt, but in a jacket, and preferably with grey or white hair so we know there are many years of accumulated experience. These are among the traits we look for as immediate indicators of expert legitimacy. But it’s also white, English, German-, or French-speaking men with grey hair who have shaped the Western philosophical discipline for centuries. This is why topics that are not so obvious to them – including menstruation, childbirth, oppression, Indian, Chinese, or Arabic philosophy, epistemic injustice, and colonization – have not yet become part of the canon; and neither have texts, thought experiments, or methods that help us understand these topics. Yet, moving outside the canon makes it difficult to defend legitimacy. As a minority – as a non-stereotypical philosopher – you’re thus caught in a double bind. Your legitimacy is questioned, so scholasticism becomes your primary weapon: “Look, I know the jargon; look, I distance myself from the body, from (my) culture, and from (my) history.” But meanwhile, scholasticism helps to perpetuate a philosophy that’s incomplete, conservative, and rigid, discouraging engagement with new topics. The battle for identity as a philosopher is thus filtered into the battle for credibility and against bias. It’s the stereotypical philosophers who get to determine new initiatives – perhaps just because their legitimacy is far less likely to be questioned. Thomas Kuhn, who had many of the traits of the mainstream philosopher (he was a white American male) faced far fewer questions about legitimacy, despite his background being in physics and despite his historical methodology.

The legitimacy of speaking on philosophical topics becomes deeply dependent on whether someone credible appears as a ‘philosopher’. Haraway and Kristeva are unlikely candidates for canonical philosophers because they combine challenges to standard views with a failing to be philosopher stereotypes. Their status as philosopher queens is controversial because their disciplinary legitimacy requires justification: it must be proven that they are doing philosophy. But this justification must be grounded in demonstrating a relation to a discipline that has no well-defined shape. Their best bet would have been to aim for the conservative centre.

Let me end with a satirical parable from Philip Kitcher’s 2023 book, What’s the Use of Philosophy. He tells a story of musical talents who train in academies to become specialists in Mozart. Initially, there’s great enthusiasm, both musicians and the public attend their shows; but gradually the improvements in the Mozart performances become smaller and smaller, and the general public loses interest in the subtle variations that can only be made out by trained experts. Some musicians also get bored. They start writing their own music, or they take up Chopin or Satie. The experts are horrified, and they exclude these ‘frivolous’ creative or Chopin-playing musicians from the academies. As time goes by, the academies’ concert halls empty. Only tenacious experts with a special ear for variations on Mozart still give concerts for each other, while the rest of the population live their lives elsewhere. The scholastics agree that the population lacks taste, and that any criticism from them is simply due to their poor judgment and lack of understanding. In this way, what started as a genuine interest in musical development has become a rigid disciplinary regime, which excludes anything that could challenge, innovate, or move the musical boundaries. Just so, canonization, jargon, and scrutinized succession to the philosophy throne may be beneficial in nurturing specialisation and quality-assurance, but it’s also exclusionary, and when adhered to too strictly, it defines a dying philosophy that, hopefully, will satisfy few philosophers.

The parable lesson, and the suggestion of this essay, is that there is something to be gained if we treat philosophers less like royals, and display a curious rather than a suspicious attitude to questions of philosophical legitimacy.

© Helene Scott-Fordsmand 2024

Helene Scott-Fordsmand is a research fellow at Clare Hall, University of Cambridge, working in philosophy of science and medicine.

• This text is developed from an earlier Danish version, published in Baggrund X Golden Days (2022).