Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Metaphors & Creativity

Ignacio Gonzalez-Martinez has a flash of inspiration about the role metaphors play in creative thought.

The equivalence between Richard Feynman’s and Julian Schwinger’s distinct formulations of quantum electrodynamics was by no means obvious. The two physicists themselves saw their methods as competing instead of being complementary. However, after becoming familiar with both approaches, Freeman Dyson had a ‘flash of illumination’ about how to reconcile them, while travelling home in a Greyhound bus. Thus it came to pass that Dyson secured yet another place for himself in the history of physics. And in his book The Emperor’s New Mind (1989), Roger Penrose recounts Henri Poincaré’s narrative of the moment when his search for ‘Fuchsian functions’ came to completion while in the middle of a geological expedition. It turned out, exclaimed Poincaré, that “the transformations I had used to define the Fuchsian functions were identical with those of non-Euclidean geometry.” The answer was ‘staring at him in the face all along’, as they say.

Such ‘flash of inspiration’ narratives, in which a coveted creative breakthrough almost violently irrupts into the mind of an ecstatic subject, surely are the archetypal depiction of creativity. This archetype suggests, not particularly subtly, that creative insight is a phenomenon that happens to the subject, not something the subject deliberately produces. Framed in this way, the mystery surrounding creativity becomes, who or what plays the active role in it?

Hypotheses about what lies at the onset of creativity abound. Sometimes people report that ideas ‘come down’ to them, even when they’re not conscious. An example of this is the story told by the German physicist August Kekulé, who claimed to have envisioned the hexagonal structure of the benzene molecule while he was sleeping. In his dream, dancing atoms formed a closed string that subsequently transmuted into a snake eating its own tail.

What’s the deal, then? Do we live immersed in a ‘creative aether’ that instigates strokes of genius in the brains of conscious and half-conscious subjects alike? Quite unlikely, if you ask me. Nevertheless, there is clearly a demystification task ahead of us if we want to understand the machinery of creative thought.

Penrose himself starts peeling out the mystery. In his view, the creative process has two stages. First there is a largely unconscious putting-up stage, where the person comes up with numerous ideas in a rather unsystematic manner. Second there is a conscious shooting-down process, where only the ideas that are judged ‘good enough’ after careful scrutiny survive and are pursued further.

Penrose’s two-step creative process is naturalistic in spirit, and a good initial sketch of a mechanistic account of creativity. And yet the diehard mystic might ask, in a loaded tone: But who or what exactly is busily putting those potentially brilliant ideas up to be shot down by a discerning mind?

Here I want to advocate for a fully naturalistic mechanism to play the role of the ‘prime mover’ of creativity. I’ll argue that the cognitive processes responsible for generating metaphors hold the key to understanding the nature of creative thought more broadly. As Pierluigi Assogna writes, “The importance of metaphorical thinking in promoting creative ideas has been widely discussed for many years” (Metaphors and Similes for Creativity, 2012). Where there’s much smoke, one reasonably intuits the presence of a fire, and I intend to add fuel to it. So my key question here is: what is it about metaphors that could promote creativity?

A question like this could accept various answers depending on the type of analysis. A bottom-up type of answer might start from the neurological foundations of metaphorical thought, then build up from there. Investigation of this idea might involve putting subjects into fMRI scanners, getting them to be creative, scanning their brains as they attempt to let the creative juice burst, seeing which brain areas light up in what sequence, comparing the patterns of activity to those observed in the brains of people as they think metaphorically, and looking for correlations.

Of course, plenty of people have written extensively about the neurological underpinnings of creativity. But alas, this is not the approach we will take here: I don’t own an fMRI machine, and I’m not trained to interpret fMRI data! Instead, here I’ll present what could be called a ‘cognitive’ approach to the question of the link between metaphors and creativity.

Image © Sylvie Reed 2024

Metaphors as Tools for Cognition

One familiar definition of a metaphor is that it is essentially a figure of speech which uses one thing to mean another by making a comparison between them. But as handy as this definition is, this level of understanding does not sufficiently expose the most interesting and defining characteristics of a metaphor.

George Lakoff and Mark Johnson triggered a load of research into metaphorical thought with their book Metaphors We Live By (1980). Their deep incursion into the mechanics of metaphor begins by defining a metaphor as: “a cognitive process that allows one domain of experience, the target domain, to be reasoned about in terms of another, the source domain.” They then argue that there’s a rule of thumb that metaphors should follow: the target domain tends to be more abstract than the source domain, which, conversely, is rather concrete. It is in this abstract-to-concrete mapping where the power of metaphor lies. But to illustrate how metaphors bring home hard-to-grasp ideas by linking them to more concrete ideas, let’s use an example: ‘Love is war.’ This seemingly uncomplicated idea in fact spans a dense linguistic network whose threads become apparent when people say things like ‘We need to fight for this relationship’; ‘You need a strategy to conquer her heart’, etc. The borrowed concepts from the concrete domain war help us to intuitively understand features of the abstract domain love.

Not every instance of metaphorical thought is that conspicuous. Metaphorical speech is ubiquitous, but usually so subtle that it escapes our notice. When we say ‘that price is too high’, we are applying the ‘up is more’ metaphor. When we say ‘I want to spend more time alone’, we’re using the ‘time is a resource’ metaphor. When we say ‘it’s good to plan ahead’, we use the ‘front is future’ metaphor. And so on and so forth. Indeed, metaphors are so pervasive in language that the claim that metaphors generate language should not seem particularly radical. If one additionally subscribes to the common sense claim that language and thought are tightly intertwined, then one should feel compelled to consider that some essential aspects of thinking are metaphorical in nature. Steven Pinker takes this idea further: “Mental metaphors are innate. Cross-domain mappings are the result of co-opting neural machinery that evolved for perception and action to support more abstract thinking” (How The Mind Works, 1997). So it’s not just that the ‘cross-domain mapping’ characteristic of metaphors underlies a lot of our cognition, it’s that no one taught us to think this way: rather, evolution built into us algorithms to conceptualize the world using metaphorical-style mappings, in the following sort of way:

1. We perceive the world.

2. We break our perception into pieces (objects, actions, events) that we group into conceptual domains based on how the pieces are perceived to occur together or to cause each other. For example, the weather changes in a relatively regular way throughout the year, so we 'break' the regular weather cycle into discrete ‘seasons’ and we invent myths to explain why they follow each other in the way they do.

3. We bridge domains through metaphorical-style thinking, and that endows us with the capacity to abstract principles to better understand the world.

Certainly this type of cognitive operation – going from perceiving, to categorizing, to connecting, to abstracting – is crucial to our capacity to reason. So we started with a humble definition of metaphor as a mere ‘figure of speech’, and we’ve ended up discovering that this unassuming concept might be at the core of what makes us distinctively human – our capacity to reason.

Analogies are Metaphors Unpacked

Let’s engage in a little exercise. Take the pervasive metaphor ‘ideas are food’ that comes into play when saying things like:

1. Yesterday’s lecture was pure food for thought.

2. I am still digesting that last thought.

3. I need to chew on this idea for a while.

4. What you said left me with a bitter after-taste.

By dissecting these sentences, we can get a better grasp on some complicated cognitive processes involved in handling ideas. Sentence 1 defines the metaphor. Sentence 2 expresses how understanding an idea is a lengthy and energy-consuming process, just like digestion. Sentence 3 suggests that examining an idea in real time is akin to arduously munching on something before we can ‘swallow’ it. Finally, sentence 4 reminds us how, after we have ‘chewed’ on an idea and fully ‘digested’ it, its implications can instigate an emotional response. We know that we’ve proposed a fruitful metaphor when by exposing more facets of the conceptual connection endorsed by it (‘ideas are food’), we progressively gain a better understanding of the more abstract concept (‘ideas’) at the expense of the more concrete one (‘food’).

However, we usually use metaphors in a scattered way, which is to say, we mix them: the typical train of thought is more likely to contain a mishmash of separate metaphors, each one with its own conceptual connection, rather than unfolding a single metaphor in a prolonged manner. This is not bad per se – except that, having to jump from one metaphorical framework to another means the full clarifying power attainable by sticking to a single metaphorical theme remains largely untapped.

Take a look at this example:

“Nowadays it is very fashionable to think in terms of networks. Antiquated conceptions of isolated agents won’t cut through the challenges. These types of ideas simply ran out of power.”

Three metaphors have been sequentially applied: ‘ideas are fashion’ (fashionable, antiquated); ‘ideas are sharp objects’ (won’t cut); and ‘ideas are machines’ (ran out of power). Together they get a message across: the speaker is urging us to abandon the ‘isolated agent’ paradigm to adopt a more holistic ‘network’ paradigm. Metaphors deployed in this way are good enough for many purposes of communication… It’s just that they can do much more when pursued more systematically. That’s what analogies do. When you offer an analogy, essentially you’re taking your listener on a guided field trip through a well-defined metaphorical map. Furthermore, analogies use metaphors to justify their own aptness. As we’ve seen, metaphors build bridges between conceptual domains: an analogy explores several of those bridges while simultaneously explaining the reasons why they’re sound.

For an example, let’s take the metaphor ‘brains are computers’ and make an analogy out of it. All the italicised words pay homage to the underlying metaphor. The full analogy unpacks this metaphor and in doing so, turns into a powerful didactic device:

The brain is like a computer insofar as it’s an information processing device: it returns an output to multiple types of stimuli that constitute input signals. When you lock your attention on a task, you use as much working memory as the task demands. Whenever information that’s not readily available is needed, you browse through your ‘ read only memory’ database to retrieve the necessary data. If useful data is not found, then you need to compute an entirely novel solution. The information itself is coded in circuits of neurons. At first approximation, the neurons are binary systems with on and off states: firing and non-firing.

Metaphors are ubiquitous and come naturally to us; we can’t communicate efficiently without them. In contrast, analogies are arduous and deliberately crafted. They show us how to methodically translate elements from one conceptual domain to another. But there’s more. Given that to construct an analogy you need to switch yourself into full introspective mode, analogy-crafting often illuminates new ideas that had been hiding from your own mind’s eye. A similar phenomenon is experienced when one attempts to articulate complicated ideas in writing. So writing is like steroids for thought. Did you spot the metaphor? If analogies have the power to focus your attention on information you already possess but never consciously noticed, then they should be considered tools to pump up the creative muscles of your brain.

The Metaphorical Nature of Creativity

Hopefully by now it should not seem so arbitrary to speculate that metaphorical thought could lay at the onset of creativity, or more specifically, the task of generating connections between two conceptual domains and consciously tying them together in an analogy-type which is typical of creative thinking. Further, it seems that a kind of scattershot bridge-building process between conceptual domains could be a central mechanism in Penrose’s ‘putting-up’ stage of the creative process. Afterwards, something like a coherent integration of metaphorical links into an analogy-like structure could often be the culmination of his ‘shooting-down’ stage.

Cased closed? Not quite. What do we make, for example, of how Albert Einstein described the nature of his creative thought process? He recounts:

“The words or the language, as they are written or spoken, do not seem to play any role in my mechanism of thought. The psychical entities which seem to serve as elements of thought are certain signs and more or less clear images which can be ‘voluntarily’ reproduced and combined[…] The above-mentioned elements are, in my case, of visual and some of muscular type. Conventional words or other signs have to be sought for laboriously only in a second stage, when the mentioned associative play is sufficiently established and can be reproduced at will.” (Albert Einstein, Ideas and Opinions, 1954)

Does this fit with what I’ve argued so far? Maybe partially.

Let’s start at the end. Einstein considered that verbalizing the visual scene playing in his imagination was the final ‘laborious’ stage of his thought process. This deliberate, difficult structuration seems of a piece with the analogy-building step at the end of the creative thought process I mentioned. But what about the crucial purely geometrical or otherwise visual fraction of his ‘mechanism of thought’?

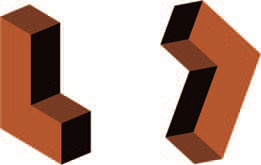

Luckily, it’s easy to see that language-free thought is absolutely possible. A simple thought experiment can demonstrate that. We can look at two images of shapes, then ask if they are the same shape (see diagram):

The way most of us will consider that question is by mentally rotating one shape until it matches the other, or not. What we would not do is narrate to ourselves the progress of the mental rotation as we perform it. Was any metaphorical thinking needed to perform the mental rotation? Not really. Is there any metaphorical operation necessary to play out mental movies? Not really. So to be clear, not every form of thought is metaphorical in nature. That’s not the claim I’m arguing for. Language-free geometrical thinking is not necessarily metaphorical. However, it can promptly acquire metaphorical characteristics when it’s used to visualize a real world phenomenon. This is likely the kind of thing Einstein was doing.

Well, we cannot know exactly what Einstein’s mental movies looked like, but we can advance an educated guess. In his Nobel-winning paper ‘Concerning an Heuristic Point of View Toward the Emission and Transformation of Light’ (1905), Einstein wrote, “the energy of a light ray spreading out from a point source is not continuously distributed over an increasing space, but consists of a finite number of energy quanta which are localized at points in space, which move without dividing, and which can only be produced and absorbed as complete units.” This passage opens a door into Einstein’s mental movie theatre. The actors that play the role of light quanta moving as ‘complete units’ conform neatly to the ‘light is a particle’ idea.

It doesn’t take much squinting to notice that this idea has a quintessential metaphorical structure: to say either that ‘light is a particle’ or that ‘light is a wave’ are expressions of metaphorical modes of thought, since it is not to say that they are only either. Indeed, in quantum mechanics, the type of experiment itself will strongly bias the experimenter to conceive of light as a particle or as a wave. In either case, the corresponding metaphor will instantaneously transform into an actual factual description. That is to say, on our current understanding, photons are best conceived as excitations of the electromagnetic field – that is, as waves. But what concerns us here is that sometimes light is imagined as an actual ball-like particle, and sometimes as an actual wavy-wave, with both of those conceptualizations essentially being metaphors.

Metaphors & Scientific Breakthroughs

The metaphorical representations ‘light is a particle’ and ‘light is a wave’ both had a shot at being the true-to-the-bone objective description of real light; but both representations are so internalized in the minds of many physicists that their metaphorical character is hardly ever recognized.

More explicit metaphorical allusions can be easily found in the very names of scientific ideas: we have for instance black holes, the holographic principle, the Big Bang… These names instantaneously evoke concrete concepts – holes, holograms, explosions – whose supporters argue help us conceptualize the object or event, or even more importantly, to mentally represent them in an abstract manner. Moreover, when we verbally explain these physical concepts, we inevitably employ metaphors and analogies. The analogies are aimed to address various questions. For example, in which ways is an astronomical black hole just like, well, a hole? Surely not in many ways. To what extent can one understand the holographic principle of the universe by understanding how a hologram works? To a remarkable one. How much was the initial expansion of space and time just like an explosion? Well…

But there are other questions that are even more pressing, given the topic of this article. How did thinking about holes, holograms, and explosions help scientists to better understand black holes, holographic principles, and the Big Bang? Did concrete concepts play a pivotal role in the mental movies playing in their minds? To what extent does constructing analogies and identifying points of departure help in refining theories? And at what point did the power of imagination prove insufficient for progress, and mathematics had to take the lead? There is likely no generic reply to any of these questions – the answers surely vary widely from one case to another. For instance, the holographic principle is notably less intuitive than the Big Bang, so surely the mind’s eye has an easier time visualizing the latter than the former.

In fact, there are numerous cases in which scientists urge us to apply metaphorical transformations not only to improve our understanding but for making actual progress. For example, with some dismay, Geoffrey West writes in his book Scale (2017): “Energy is primary. It underlies everything that we do and everything that happens around us… This may seem self-evident, but it is surprising how small a role, if any, the generalized concept of energy plays in the conceptual thinking of economists and social scientists.” He’s indirectly urging economists and sociologists to import the concept of energy from physics and apply it to their disciplines. But the question remains: Is ‘energy’ as a concept concrete enough to clarify whatever abstract concepts sociologists and economists are dealing with? I, like West, strongly suspect that it is. West also suggests that a metaphorical transaction centered around the concept of ‘metabolism’ might be apt to encourage progress in the social sciences. Comparing natural organisms with social systems like cities and companies he writes, “None of these systems, whether ‘natural’ or man-made, can operate without a continuous supply of energy and resources that have to be transformed into something ‘useful’. Appropriating the concept from biology, I shall refer to all such processes of energy transformation as metabolism.”

One can find many examples of awe-inspiring creative breakthroughs rooted in metaphorical thinking. For instance, get a copy of Linked by Albert-László Barabási and Jennifer Frangos (2002), and check out the connection between the Bose-Einstein condensate and a model of the World Wide Web realized by Ginestra Bianconi; it is truly something. But there’s just one more case in point that I can’t fail to mention – the metaphoric nugget at the core of perhaps the most significant single idea anyone has ever had: evolution by natural selection. Charles Darwin dedicates a large initial chunk of The Origin of Species (1859) to talk about breeders – pigeon breeders most of all. He meticulously explains how the physical characteristics of pigeons can be shaped through artificial selection by human breeders, to the extent of creating barely functional creatures like tumbler and fantail pigeons, or nasty-looking monstrosities like dragon pigeons (he didn’t describe them in such contemptuous terms: those are all mine). Only after the workings of artificial selection were well established, did Darwin make the move of replacing human action as the selective agent with the natural environment as the agent. By using the quintessential metaphor ‘nature is a choosing agent’, Darwin then gives us the theory of natural selection. Of course, there is much more to the story; but it’s clear that thinking of nature as an agent played a big role in his thought process.

So what do you think? Do you think metaphors are just pleasing figures of speech?

Think twice.

© Ignacio Gonzalez-Martinez 2024

Ignacio Gonzalez-Martinez is a physicist working in the semiconductor industry after doing research for over a decade.