Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Pythagoras (570-495 BCE)

Daniel Toré looks beyond the mathematician to the philosopher.

“Isn’t he the guy that invented triangles?” – Student of mine, 2023

Pythagoras of Samos is, without dispute, one of the towering figures of ancient philosophy. Any first-time reader of classical philosophy will inevitably be welcomed by the Big Three: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and before leaving, they may give a polite glance at the Presocratics, before never looking back. However, in that over-the-shoulder moment, they will see some of the most intriguing and unique thinkers philosophy has to offer: Anaximander, Heraclitus, Parmenides, and amongst their number, the only deer in the herd with horns: Pythagoras. Considered more than merely human by some of his followers, Plato described him as ‘a semi-divine master’. Or to quote Anthony Kenny, he is “honoured in antiquity as the first to bring philosophy to the Greek world…” (An Illustrated Brief History of Western Philosophy, 1998, p.1). Pythagoras also holds the VIP distinction of being a name recognised even by non-philosophers. However, even historians of philosophy might have a hard time describing his philosophical work, without just simply recalling how he was an influence on Plato. Still, it cannot be denied that the ripples created by this obscure character roughly 2,500 years ago are still moving today – although he himself is still a mystery.

How can somebody be that famous, and yet still unknown? That influential, and yet still ignored?

Simply put: just who exactly was Pythagoras?

Pythagoras by Clint Inman

Simply answered: we don’t really know. In terms of both his work and biography, it’s difficult to tell what can be accurately attributed to him and what’s just a product of his fame.

The most frustrating part of exploring the lives of the very early philosophers, is that we quickly realise how exceedingly little we know. This problem is multiplied when dealing with Pythagoras, who was born a hundred years before Socrates. On top of that, he insisted that no one close to him should write down what he did or said. This means that everything we know about him is either second-hand (through some disciple leaking his work against Pythagoras’s will), or third-hand (like the discussions found in Plato and Aristotle that were reactions to the second-hand knowledge, and written well over a century after Pythagoras’s death). All of this creates an apocryphal character that distracts from the true person. But imagine you had only ever heard rumours about a person, and those rumours just keep getting odder. This would inevitably lead to the idea you have of the person will be entirely removed from the truth. But my goal here is to see what can be found underneath all the bizarre stories. Who was the real Pythagoras of Samos?

Early Life

Even during his life Pythagoras had a cult following, whose members embellished a lot about him to add to his already overblown status. For example, they claimed that he was the son of Apollo. Pythagoras’s father had been away on a long sea voyage, and upon his return found that his virgin wife was pregnant – but any suspicions of adultery were dispelled when Pythagoras was born and they discovered a golden birthmark on his thigh (birthmarks were typically considered symbols of divinity by the Ancient Greeks, who also associated the colour gold with Apollo, the sun god). According to Aristotle, Pythagoras loved to show off his birthmark at public events, and made sure that everybody knew about his supposedly divine origins. On top of this, he claimed to be the reincarnation of Aethalides, son of Hermes – as if one god parent wasn’t enough. Another claimed past life of his, was that of Euphorbus, a hero from the pages of Homer. His followers also claimed that he could speak to animals and predict earthquakes.

What we do know for certain is that Pythagoras was born around 570 BCE on Samos, an island in the eastern Aegean Sea.

Pythagoras’s hazy birth is followed by a collection of hazy accounts of him traveling the ancient world, picking up new ideas on mathematics and philosophy that would influence him later, possibly including his famous theorem. It’s no secret that Pythagoras’s triangle theorem – the bane of children’s maths classes – had already been discovered by the Babylonians a thousand years before Pythagoras was born. The theorem could have easily travelled from Babylonia down to Egypt to be picked up by a visiting Greek mathematician. Why we associate the idea with Pythagoras is up for debate, too. Some say that he was the first to conclusively prove it, thus taking it from a theoretical to a practical basis. But this may just be speculation.

Either way, it seems clear that Pythagoras did some traveling; though when, where, and why, are also open to interpretation. There are stories of his being kidnapped and sold into slavery, where he quickly bought back his freedom; but details on this differ too much for the stories to be reliable. There are also some conflicting accounts that describe how, as a young man, Pythagoras met and studied under Thales of Miletus. This might not sound much; but if true, it’s the Presocratic equivalent of when the Beatles met Elvis! Unfortunately, I have found no real evidence this meeting ever took place, and the only reason to think that they might have met is because they’re both Greek philosophers and their timelines overlap.

Greece To Italy

After spending his youth island-hopping around Greece, Pythagoras settled in Crotone, on the heel of Italy, where he was to spend the remainder of his life. There he founded a school.

Ancient philosophers loved to found schools. Plato established his Academy in Athens, as did Aristotle with his Lyceum. What made Pythagoras’s school unique was its packaging. Ancient Greek philosophy schools weren’t so far removed from what we’re used to now – in fact, our schools are based on their system. Students would arrive for morning lectures by a master. Afterward, notes from lectures would circulate amongst the students. But from what I can gather, Pythagoras’s school was more of a squat, or as I said, a cult, where members were expected to live, and to follow certain rules. This society, which was exceptionally progressive at that time, in allowing both men and women, had an inner and an outer circle. Inner circle members were named the Matematioki, and were not permitted to eat meat or own property. The outer circle, referred to as the Akousmatics, were more like part-timers, and weren’t bound by as many of the rules, but were nonetheless members.

The Pythagoreans, both the Matematioki: and the Akousmatics, are often dismissed as a cult, but that modern term has far too many connotations to be quite accurate. Pythagoras’s was indeed odd: it had a famously whacky set of rules (no lentils!), and members weren’t allowed to interact with outsiders. At the same time, they had a single figurehead whom some members thought had supernatural properties – which would normally be enough to set off the cult alarm. It really comes down to how you define a cult. In defence of the Pythagoreans, we don’t know how much of what is said about them is legitimate, and what was made up by Athenian haters. However, they did refer to themselves as The Pythagorean Brotherhood.

At its core, the Brotherhood was somewhere in-between a study circle and a religion. As far as we can tell, the central beliefs of the Brotherhood were as follows:

1. That reality is mathematical;

2. That philosophy can be used for spiritual purification;

3. That the soul can rise to union with the divine; and,

4. That certain symbols have mystical significance.

It was also required that all brothers of the order should observe strict loyalty and secrecy.

The loyalty commandment is especially concerning. For example, the philosopher, mathematician, and one-time member of the Brotherhood, Hippasus, is said to have discovered irrational numbers – numbers which can’t be represented as fractions. One will occasionally see this discovery credited to Pythagoras, but this is due to the Greek tradition of students signing their ideas with their teacher’s name rather than their own. But we can guarantee that this was a genuine Hippasusean idea, since Pythagoras believed that all numbers are either integers or their ratios (fractions). We have to thank Hippasus for his groundbreaking discovery, then, and commend his bravery for divulging his findings to people outside of the Brotherhood, thereby breaking the commandant.

What happened to Hippasus is fuzzy. We do know that he drowned. The question is whether his drowning was an accident or not.

Philosophy or Mathematics?

In terms of Pythagoras’s philosophy, the first belief is the most significant. Pythagoras believed that reality itself is mathematical in nature: everything that is can be broken down mathematically, or described using numbers. This is no big surprise for the modern reader, who most likely thinks of the world from a scientific, mathematical angle; but the reason we think this way is due to thinkers such as Pythagoras. There are, for example, multiple accounts of Pythagoras’s pondering the relationship between sounds and numbers, and it was his way of understanding reality that led to his discovery that a string on an instrument that’s exactly half the length of another will play a pitch exactly twice as high. In other words, Pythagoras successfully described in mathematical terms the relationship between string lengths and musical pitch, thereby connecting the abstract concept of numbers with the physical world. Pythagoras then began to pay close attention to the movements of the stars and planets. He began to teach the Brotherhood that the Earth was not the centre of the universe. Instead, it – along with the Moon, Sun, and everything else in the sky – were moving in immense circles that could be recorded and predicted. (This view began to be taken seriously again two millenia later when Copernicus developed his theories, which he aptly titled Astronomia Pythagorica.) These kinds of discoveries must have had a kind of dizzying spiritual effect on Pythagoras, since he and his clan soon began to literally worship the numbers they were studying.

It feels unnatural to us now, but the Pythagoreans saw no reason to separate what we would call a scientific world view from a mystical one. Rather, their understanding of reality can perhaps best be summarised by their mantra ‘All is number’. They meant that everything that exists must be describable in mathematical terms; and if all things can be broken down in this way, then it must be mathematics that determines everything.

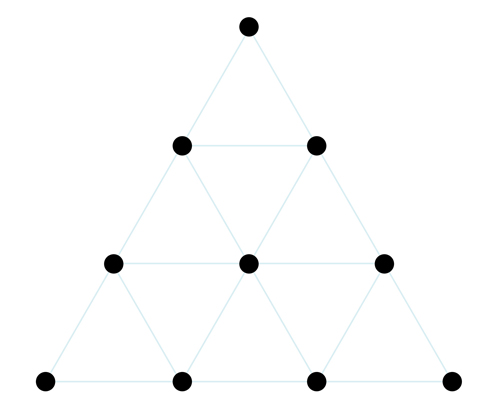

This looks like a clear piece of reasoning. However, Pythagoras and his cronies tend to lose their audience when they extend this idea to literal worship of numbers, such as the Tetractys:

This supposedly ‘holy’ symbol can be found in Jewish mysticism, Tarot cards, as well as in how we arrange bowling pins. But for the Pythagoreans it symbolised a host of different concepts – such as the four elements: air, fire, water, and earth. It also represented how the four dimensions build on top of each other to construct reality: the first dimension as the base, layered by the second, and so on.

The Pythagorean veneration of this symbol extended to new members of the Brotherhood being required to swear a secret oath by the Tetractys, after which they were required to keep a vow of silence for five years. By all accounts, the Brotherhood regularly recited the following prayer:

“Bless us, divine number, thou who generated gods and men! O holy, holy Tetractys, thou that containest the root and source of the eternally flowing creation! For the divine number begins with the profound, pure unity until it comes to the holy four; then it begets the mother of all, the all-comprising, all-bounding, the first-born, the never-swerving, the never-tiring holy ten, the keyholder of all.”

The oddness of the Pythagoreans can be quite distracting; but one must remember that Greek culture already worshipped abstracts, simply personified into deities. The Olympian gods were representations of concepts such as wisdom, strength, order, and so on. So for Pythagoras to extend prayer to something he believed to literally govern reality was quite a natural progression. And, as I said, the Brotherhood saw no reason to separate the scientific from the mystical – in fact, Pythagoras probably wouldn’t have grasped the distinction. From what we can gather, he would rather have distinguished reality into what can be described as ‘stable’ and ‘unstable’. The earlier Presocratic philosopher Anaximander (610-546 BCE) had described the cosmos as being composed of two distinct substances: Apeiron (the limitless) and Peiron (the limited). In modern jargon, he would be referring to, first, the substance and space of the universe, and second, the shape that the substance can take; that is, as objects we can observe. This would have been how Pythagoras conceived the universe, too – albeit governed by mathematical precepts. This led to his formulating a radical new way of understanding ourselves, namely dualism. Dualism is the idea that reality can be separated into two independent parts: usually, the material and immaterial, or to use more controversial words, body and soul. To quote Peter Adamson’s Classical Philosophy (2014): “Plato and the followers of Pythagoras were interested in… stable, immaterial objects. They wanted to get away from the messiness of physical things, with their constant change and their being subject to an infinite number of various features.” Thus Pythagoras nurtured his interest in the stable, eternal and unchanging elements of the soul and of numbers – so paving the way for both Plato and Descartes.

Triangles et Couleurs © Lenny Ellipse 2020 Creative Commons 4

The End of the Brotherhood, and of Pythagoras

It may be precisely this dualistic conception of the cosmos that is to blame for Pythagoras’s death. He and his tribe of dangerous dorks held that the human body was the finite vessel of an infinite soul that escaped upon the body’s death to find a new host. We might call this ‘the transmigration of the soul’, though Pythagoras would probably have used the Greek word we translate as ‘soul’, psychē, to mean ‘conscious life-force’, without the modern post-Christian connotations of ‘soul’ (having said that, it was one’s psychē that went to Hades after death). According to Pythagoreanism, the psychē would move from one body to another after death, and so could upgrade or downgrade into different lifeforms. This was the reason for the Brotherhood’s strict vegetarianism, since the chicken you’re nibbling on may contain the psychē of a former human, perhaps even a relative. Pythagoras even taught that beans had an especially fetal-shape and fleshy texture because they were containers for new souls. Thus, eating beans was tantamount to cannibalism. The Brotherhood were forbidden to even handle them, for fear of damaging them.

In the year 495 BCE, an angry mob descended on the Brotherhood to drive them out of town: the tribe’s reputation, secrecy, and aversion to normal life had proven too much for the locals. The mob was roused to fury by the disgruntled white-knuckle Kylon, whose application to join the Brotherhood had been rejected. As it stabbed and burned its way through the Matematioki, the elderly Pythagoras slipped out the back and was hightailing it across the fields when he was stopped in his tracks. Before him was a vast bean field. He hesitated Pythagoras had to choose either to risk crushing the beans underfoot, or to allow the quickly-approaching horde to catch up with him. Before he could make up his mind, his blood was spilled on the plants below.

© Daniel Toré 2025

Daniel Toré is a philosophy teacher in Sweden and member of the British Wittgenstein Society.