Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Fire This Time

Tim Madigan on Ray Bradbury, Bertrand Russell and Fahrenheit 451.

“If I were asked to describe my ideal ‘intellectual-with-a-small i’ I would do it thus: a person who can start an evening with Shakespeare, continue with [Fu] Manchu and James Bond, jog further with Robert Frost, cavort with Moliere and Shaw, sprint with Dylan Thomas, dip into Yeats, watch All in the Family and Johnny Carson, and finish up the morning with Loren Eiseley, Bertrand Russell and the collected cartoon work of Johnny Hart’s B.C.”

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012)

Ray Bradbury’s novel Fahrenheit 451 was published over seventy years ago, in 1953, and yet continues to be a source of controversy, being banned by many school boards, libraries, and other institutions throughout the United States – an ironic fate for a novel about literary censorship.

On March 13, 1954, the philosopher Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) wrote a letter to Bradbury’s London publishers praising Fahrenheit 451, and enclosing with it a photo of himself, pipe in hand, with a copy of the book on the arm of his reading chair (the photo became one of Bradbury’s most cherished possessions). Russell wrote:

Dear Mrs. Simon,

Thank you for your letter of March 8 and for Ray Bradbury’s book Fahrenheit 451. I have now read the book and found it powerful. The sort of future society that he portrays is only too possible. I should be glad to see him at any time convenient to us both, and perhaps you might ask him to ring me up when he returns from Ireland and then we can fix a time.

Yours sincerely,

Russell

Unbeknownst to Russell, Bradbury – a Los Angeles native who hated to fly and seldom left the United States – was actually not in Ireland (where he had recently gone by ship from America to work with director John Huston on the screenplay for a film adaptation of Moby Dick), but was in fact in London at the time, en route to joining his family on a vacation in Italy. After reading the letter at his publisher’s London office, Bradbury called the number on it and spoke with Russell, letting him know that he would love to meet, but that, unfortunately, it would have to be that very day, April 11, 1954, as he had to leave London the next day to meet his wife and daughters in Sicily. Bradbury feared that he was being presumptuous for insisting on a visit at such short notice, but was delighted when Russell said it would be fine.

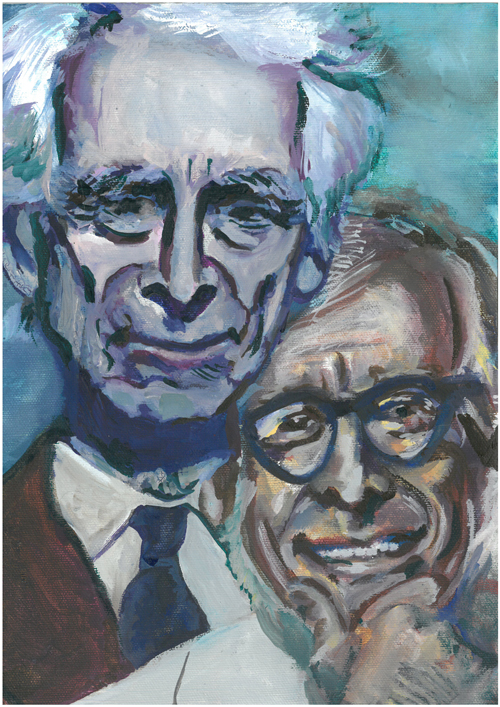

Russell & Bradbury by Gail Campbell

Bradbury described his visit in a chapter entitled ‘Lord Russell and the Pipsqueak’ in his 2005 collection of essays Bradbury Speaks: Too Soon from the Grave, Too Far from the Stars. He wrote: “So promptly at 7:00 P.M. I left Victoria Station and was hurled forward much too quickly for my rendezvous with the world’s greatest living mind. On the way I was struck a tremendous blow. What, my God, would I say to Lord Russell? Hello? How’s things? What’s new? Good Gravy and Great Grief! My soul melted to caterpillar size and refused the gift of wings” (pp.78-79). Bradbury, a self-educated man who had never attended college, and who freely admitted that most of his knowledge of philosophy came from reading Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy (1946), was trepidatious that he might be asked his opinion of Nietzsche or Schopenhauer, or, worst of all, Sartre, whose novel Nausea (1938) he had recently tried to read, “only to wind up with feelings befitting the title” (p.79). Much to Bradbury’s relief, the subject of philosophy never came up during the brief meeting – which was rather fortunate, since, according to Bradbury’s biographer Jonathan Eller, the philosopher he was most intrigued to learn about was Henri Bergson, whose metaphysical views on time and space were completely opposed to Russell’s.

Russell opened the door of his flat, and soon introduced Bradbury to his wife Edith. In Bradbury’s reminiscences of the visit she is portrayed as a mostly silent presence, sitting and knitting in the background like Madame Defarge while the two men conversed. Like most Americans at the time, Bradbury was not a tea drinker, and was appalled by the ‘heavily milked and sugared’ concoction served to him by his host, but he was polite enough to drink it anyway.

In order to forestall a deep intellectual discussion he felt ill-prepared to venture into, Bradbury came up with a brilliant opening gambit – praising Russell’s recent short story collections, Satan in the Suburbs (1953) and Nightmares of Eminent Persons and Other Stories (1954). He exulted:

“Lord Russell, I predicted to friends years ago that if you ever turned your talent to short fiction, it would be to the fantastic and science-fictional manner of H.G. Wells. How else could a thinker write than in a scientifically philosophical mode?”

In other words, he laid it on thick: as an accomplished writer of fiction, Bradbury recognized that in fact that was not one of Russell’s strong points. But Russell was pleased, saying, “Yes, yes, of course you’re absolutely correct.” Bradbury, knowing that the books had not sold as well as Russell’s nonfiction writings, or been particularly well received by critics, added that “Since I was one of the few in the entire United States who had bought his tales I was now the rare expert and expounded on their qualities” (p.80). In fact he found the premises of the stories to be thought-provoking but the character portrayals in them to be anemic and the settings perfunctory: “Bertrand Russell was, in sum, a bright amateur seeking but rarely finding the dramatic effect, accomplished only in jump-starting brilliant fancies but failing to breathe them into satisfactory lives.” This was not a criticism he related out loud to the author, however. “Was I duplicitous? No, simply young and eager to please the master.” It should be pointed out that Bradbury was, as he himself described it, ‘a teenage thirty-three’ at the time, so referring to himself as young was rather charitable; but he was almost fifty years the junior of the then eighty-two-year old Russell, so perhaps he felt young in comparison.

Russell rescued his visitor by turning the tables on him, asking about his work on the Moby Dick screenplay and how one could possibly attempt to adapt such a classic novel into a movie. Much of the rest of the essay consists of Bradbury’s descriptions of how he and Huston had grappled with this problem, stating that it was his own naïveté that led him to tackle such a monumental task. “At which point, Lady Russell paused from her soundless knitting, fixing me with a steady and unrelenting stare, and said, ‘Let us not be too naïve, shall we?’ And was silent for the rest of my stay” (p.81). Russell then came to his rescue again by asking him more questions about ‘the mysteries of film creation’. The Russells were interested in the possibility of adapting Bertrand’s short stories for the big screen; but Bradbury, whose sole movie script credit would be for Moby Dick, was genuinely in the dark about arranging such matters, since he had uniquely been specifically chosen by Huston as the screenwriter, and had no advice on what needed to be done to have one’s works adapted for the movies.

The evening ended well; then Bradbury had to rush to meet the last train back to his get to his hotel. But he couldn’t help but note that the meeting had not been as auspicious as he had hoped it would be. He ends his essay on it by musing:

“On the train rushing back to London, I cursed everything I had dared to say, much as on those nights when, taking some young woman home from a cheap film, I had hesitated at her door and backed off without so much as pressing her hand, crushing her bosom, or kissing her nose, then cursing, damning my gutless will, walking home, alone, always alone, wordless and miserable.” (p.85)

This feeling that somehow there had not been as strong a connection as he had desired is confirmed by Eller in his biography; he quotes a letter Bradbury wrote to a friend shortly thereafter:

“I may have hit Russell on an off evening. I may have had little to give him, being constrained myself. In any event, while it was a nice evening, it didn’t have that sort of feeling where your own champagne-bubbles foam up behind the eyes while you’re talking to people you’re really at ease with.” (Ray Bradbury Unbound, 2014, p.32)

The two men never met again, and Bradbury ends his essay recollecting their sole meeting by admitting that “even in writing this, suppressing my naïveté is one more act of pride to which Lady Russell is my ghost confessor” (p.86). If indeed Bradbury’s recollections, written many decades after the fact, are accurate, there is a sense of lost opportunity, since in addition to Bradbury’s work on Moby Dick there was another topic at hand that seemed a natural for them to discuss: Bradbury’s current best-selling novel Fahrenheit 451 and the warnings in it that Russell had found ‘all too possible’.

The Heat Is On

No doubt one reason why Russell had admired Fahrenheit 451 enough to invite its author to meet him was the fact that he himself appeared in it. Towards the end of the novel we read:

“Some of us live in small towns. Chapter One of Thoreau’s Walden in Green River, Chapter Two in Willow Farm, Maine. Why, there’s one town in Maryland, only twenty-seven people, no bomb’ll ever touch that town, is the complete essays of a man named Bertrand Russell. Pick up that town, almost, and flip the pages, so many pages to a person.” (p.150)

Russell’s genius, Bradbury wrote in his recollection of his visit, “was in the essay, grand and minute, not in character portrayal or the delineation of master scenes” (Bradbury Speaks, p.80). Perhaps that’s why the essays of Russell were what were remembered in the novel. Bradbury himself was well-known in science fiction circles, but not yet world famous in 1953, when he wrote the book in part as a protest against the then-ongoing House UnAmerican Activities Committee investigations along with those of Senator Joseph McCarthy on alleged Communists and subversives, which Bradbury considered to be a modern witch hunt. While, like Russell, an opponent of the totalitarian regime of the Soviet Union, Bradbury, also like Russell, opposed using totalitarian tactics in a democratic society. David Seed points out that “Bradbury has repeatedly made the purpose of his novel clear, considering it a ‘direct attack against the sort of thing [McCarthy] stood for’, and in a 1970 interview Bradbury expanded on this: ‘Well, that all came about during the Joseph McCarthy era… Everybody sort of sat around and let McCarthy throw his weight around and nobody was brave. So I got angry at the whole thing and said to myself that I didn’t approve of book burning; I didn’t approve of it when Hitler did it, so why should I be threatened about it by McCarthy?” (Ray Bradbury, 2015, p.87).

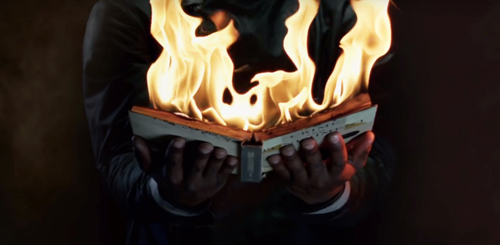

Fahrenheit 451 movie image © Rank Film Distributors 1966

Fahrenheit 451 – “the temperature at which paper catches fire and burns” according to its opening words – is the story of a future dystopian society where buildings are fireproof and firemen don’t put out blazes but rather set them, burning supposed subversive literature on the orders of the state. The lead character, Montag, is a fireman who becomes intrigued by what he has been ordered to destroy, and hides a copy of the Bible.

The story is eerily prescient, with large screens in everyone’s home, mind-numbed viewers satiated by nonstop entertainment, and the constant surveillance of citizens. Montag is turned in to the authorities by his own wife, but escapes just before a ‘limited nuclear attack’ destroys his town. He meets up with a group of fellow renegades, who tell him that there are people like themselves throughout society who have memorized many works (including the essays of Russell) in order to preserve them for posterity, and that he should join them in their efforts: “And when the war’s over, someday, some year, the books can be written again, the people will be called in, one by one, to recite what they know and we’ll set it up in type until another Dark Age, when we might have to do the whole damn thing over again. But that’s the wonderful thing about man; he never gets so discouraged or disgusted that he gives up doing it all over again, because he knows very well it is important and worth the doing” (pp.150-151).

The novel caught on, continuing to sell in large numbers right up to the present day, and remains Bradbury’s best-known work. This isn’t surprising, since censorship is still an ever-present topic, as Seed affirms: “Given the subject of Fahrenheit 451, it is a supreme irony that in 1967, unbeknownst to Bradbury, the editors at Ballantine bowdlerized the novel for a high school edition, removing references to nudity and drinking and also expletives. Although the original text was restored in 1980, the novel’s acceptance in the classroom continues to be widely debated on U.S. high school boards” (Ray Bradbury, p.121). It therefore seems odd that the constant need to defend freedom of speech was not one of the issues Bradbury and Russell discussed during their sole meeting. Still, the visit was a brief one, and Bradbury’s recollections so many years afterwards might not be completely accurate.

Though Bradbury suffered from his opposition to McCarthyism, being investigated by the FBI and having various lecture appearances unexpectedly cancelled by authorities after the novel’s publication, his own interpretation of the meaning of Fahrenheit 451 changed over time. According to Eller, Bradbury gave different reasons for what motivated him to write it, and what he thought its continuing significance was. Like many liberals (but unlike Russell), Bradbury became increasingly conservative as he aged, and by the time he was himself in his eighties he was praising Presidents Ronald Reagan and the Two Bushes, and arguing that his novel was a warning against the dangers of political correctness.

Whatever Bradbury’s intentions may have been at the time of writing, Fahrenheit 451 is still relevant. Book banning and even book burning continue, both from the Left and from the Right. In addition, the need to defend literacy – another central theme of Fahrenheit 451 – takes on greater poignancy in the digital age. Television was in its infancy when the book described gigantic screens and the twenty-four-hour programming of mindless entertainment. Seed writes that, “Bradbury’s intermittent commentary on his novel has consistently stressed the continuing relevance of its critical engagement with the media long after the specific paranoia of the McCarthy era had passed. In a 1998 interview, he stated that ‘Almost everything in Fahrenheit 451 has come about, one way or the other – the influence of television, the rise of local TV news, the neglect of education.’ And in 2007, on the occasion of receiving a Pulitzer Prize, he denied that it was about government censorship so much as ‘how television destroys interest in reading literature.’ This happens through the transmission of ‘factoids’, gobbets of useless information without context” (p.121). Seed goes on to say that Bradbury viewed his novel not as a prediction of the future, but rather as a warning against possible futures.

It’s nice to know that Bertrand Russell played a role in inspiring Ray Bradbury in his defense of freedom of thought, and that whoever now reads Fahrenheit 451 will see a reference to ‘a man named Bertrand Russell’, and may be inspired in turn to read his collected essays and other works, perhaps even his fiction!

© Dr Timothy J. Madigan 2025

Tim Madigan is Professor of Philosophy at St John Fisher University, and the Immediate Past President of the Bertrand Russell Society.