Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

The Philosophy of Pain

Vikky Leaney says pain is a problem even (or especially) when we can’t see it.

Pain is one of the most paradoxical aspects of human experience: deeply personal, yet profoundly elusive; intangible, yet undeniably real to those who feel it. For people living with fibromyalgia – a chronic condition marked by widespread pain, fatigue, and cognitive difficulties – this paradox becomes an inescapable reality. Fibromyalgia is often referred to as an ‘invisible illness’ because its symptoms lack visible signs or conventional markers that medical science can easily detect. This invisibility leads to a significant struggle for validation for sufferers, both socially and medically. Yet the challenges of fibromyalgia reach beyond personal experience, to raise philosophical questions that probe the nature of pain, the limits of perception, and the ethical dimensions of empathy. This article considers these issues, drawing from phenomenology, ethics, and the philosophy of mind, to explore how invisible illnesses like fibromyalgia challenge our assumptions about pain and our responsibilities towards others. By examining the experience of fibromyalgia sufferers, we can gain insights into how society perceives and validates suffering (or doesn’t) – and how our ethical obligations might require us to believe in what we cannot see.

Pain, Perception & the Body: A Phenomenological Perspective

For people with fibromyalgia, pain is a constant, all-encompassing presence that radiates throughout muscles and joints, affecting daily life in countless ways. This makes fibromyalgia not just a physical experience but an existential one – one that forces sufferers to confront their own bodies as sources of unending discomfort and frustration.

The experience of pain defies easy description. The words we use – ‘sharp’, ‘burning’, ‘throbbing’ – often fall significantly short of capturing pain’s intensity and the way it can consume one’s entire awareness. Yet phenomenology, the branch of philosophy concerned with describing subjective experience, offers valuable tools for understanding the relationship between pain and self.

Phenomenologists such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-61) argue that it is significant that we are embodied beings: that we experience the world through our bodies rather than as detached observers. For fibromyalgia sufferers, the body is not merely a vessel, but the site of constant pain, and pain is a companion that cannot be left behind. Their experience of reality is mediated by this pain, colouring interactions with the world, relationships with others, and even perceptions of time. Yet phenomenology highlights a fundamental problem here: While pain is undeniable to the person experiencing it, it remains largely invisible to others. This disconnect between one’s subjective experience and others’ perceptions creates a gap in understanding that even those closest to fibromyalgia sufferers may struggle to bridge. As a result, the invisible nature of pain becomes a barrier not only to understanding, but also to empathy, leaving those who suffer feeling isolated, misunderstood, and often dismissed.

The Invisibility of Pain & the Problem of Validation

The invisibility of pain presents a unique challenge in our society, where visible evidence is often required to validate a perspective. The absence of visible markers often leads to a sense that their pain is ‘unprovable’. Fibromyalgia sufferers frequently report encountering scepticism and disbelief from others, including medical professionals, and sufferers are sometimes accused of exaggeration or even fabrication. Such responses stem from the bias towards the tangible and the measurable – reflecting a broader assumption that what cannot be seen cannot be trusted.

In Western medicine, the gold standard for diagnosing illness is physical evidence: an abnormal test result, a visible injury, or clear signs of damage. Fibromyalgia defies these conventions, leaving sufferers in a precarious position where their pain is real to them but unrecognised by the diagnostic frameworks that currently define medical reality. This creates a phenomenon often referred to as ‘epistemic injustice’, a term coined by the philosopher Miranda Fricker to describe the unfair dismissal of knowledge due to bias on behalf of the dismissers. Fibromyalgia sufferers face this injustice daily as their subjective reports of pain are discounted or invalidated simply because they lack physical proof.

This demand for proof also reveals a deeper philosophical issue about how we define suffering. If we insist on physical evidence to validate pain, we risk overlooking or dismissing forms of suffering that do not fit into neat categories. And Elaine Scarry, in her influential 1985 book The Body in Pain, argues that pain has a unique capacity to disrupt language, making it difficult for sufferers to communicate their experience. Fibromyalgia sufferers, then, face a dual struggle. Not only must they endure their pain, but they must also find ways to express it – in language that often fails to capture its impact. This struggle for expression is complicated further by the social expectation that pain should be demonstrable, creating an environment where fibromyalgia sufferers feel pressured to ‘prove’ an experience that defies conventional explanation or demonstration.

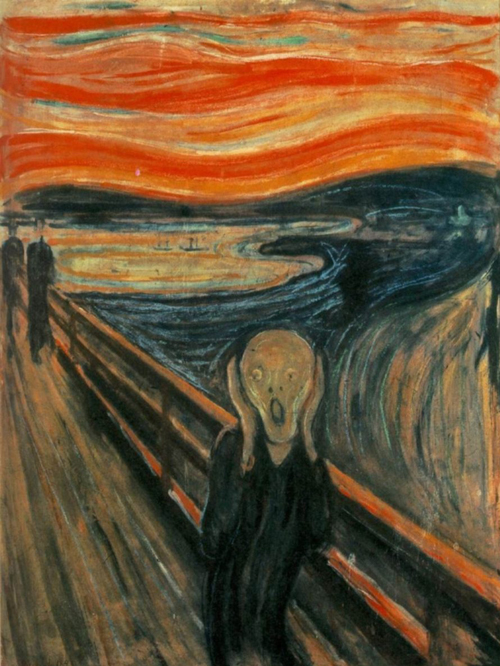

The Scream Edvard Munch 1893

The Ethical Imperative to Believe

The invisibility of fibromyalgia pain also raises profound ethical questions about how we respond to others’ suffering. If we rely solely on external evidence to validate pain, we risk neglecting the experiences of those whose suffering lies beyond our perception. This brings us to the heart of an ethical dilemma: Are we morally obliged to believe others’ pain testimonies even when they cannot be empirically verified?

The existentialist Emmanuel Levinas (1906-95) offers insights that may guide us towards an answer. Levinas argues that ethics begins with the recognition of the Other’s vulnerability, and that this vulnerability places a moral demand upon us. In the context of fibromyalgia, this means that we are ethically bound to respond to the sufferer’s pain even if we cannot see it. To do otherwise – to demand proof, say, or to dismiss the pain as imaginary – is to refuse the ethical call that their suffering places upon us.

This ethical imperative is echoed in the work of Simone Weil (1909-43), who writes that the first duty of love is to listen. Listening, in this case, means accepting another’s pain testimony without demanding physical proof. By believing in the pain of fibromyalgia sufferers, we validate their experiences and offer a form of sympathy that does not depend on visibility. This approach aligns with a broader philosophy of relationships that transcends the limitations of empirical evidence, allowing us to connect with others on the basis of trust and our shared humanity.

The issue of disbelief in invisible pain is also deeply intertwined with questions both of gender and of social marginalisation. Studies have shown that fibromyalgia disproportionately affects women, and that women’s pain is often taken less seriously by medical professionals. This pattern reflects long-standing biases that view women as prone to exaggeration. Such biases are rooted in historical practices of medical paternalism. So, by doubting the experiences of fibromyalgia sufferers, society not only fails in its ethical duty to believe, but also perpetuates a form of gender-based injustice.

Towards a Philosophy of Sympathy & Belief

Invisible illnesses like fibromyalgia invite us to re-evaluate our philosophical frameworks for sympathy and belief, encouraging a shift away from an empirically-driven understanding of suffering, towards one grounded in trust and compassion. If we are to adequately respond to the pain of fibromyalgia sufferers, we must be willing to believe in experiences that cannot be sensorially or scientifically confirmed. This requires a radical rethinking of sympathy, which embraces others’ subjective realities even when they lie beyond conventional forms of validation.

A philosophy of sympathy that values testimony over empirical evidence could have profound implications for medical practice, public policy, and social attitudes. Doctors might be trained to approach ‘hidden’ conditions like fibromyalgia with an openness to patient narratives, recognising that physical evidence is not the only indicator of suffering. Society could also cultivate a broader understanding of disability and chronic illness, which recognises that not all suffering is visible. And on a personal level, we might each practice a more intentional form of sympathy, which makes space for the experiences of those whose pain remains hidden from view.

Fibromyalgia and other invisible illnesses bring to light the philosophical complexities of pain, perception, and empathy, urging us to develop a more nuanced and compassionate approach to suffering. They also confront us with the limitations of a purely empirical worldview.

For those living with fibromyalgia, the struggle for validation is an ongoing reality that shapes their sense of self and their connection to others. For the rest of society, their pain is a call to re-evaluate our assumptions, to bridge the gap between visibility and belief, and to recognise that true sympathy requires us to believe in the expressed experiences of others, even when they lie beyond our immediate perception. So in the end, the invisible nature of fibromyalgia is not merely a medical issue, but a philosophical challenge: one that demands a rethinking of how we define and respond to suffering. By expanding our sympathy to unseen pain, we not only honour the experiences of those with fibromyalgia and other conditions, but also deepen our own understanding of the complexities of human life. Invisible pain is, after all, no less real for its invisibility, and our ethical duty is to recognise and respond to it even when it defies our capacity to see it.

© Vikky Leaney 2025

Vikky Leaney is a postgraduate researcher with a specialist interest in chronic illness and neurodivergence in women. She is currently completing her PhD on the development of a feminist biopsychosocial theory of ADHD.