Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

The Human Experience

What Does it Mean to be Human?

Vikas Beniwal considers some philosophers’ core understandings.

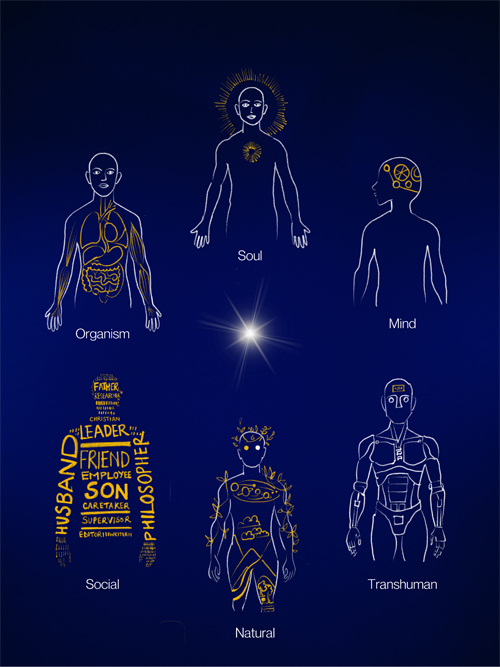

When someone asks ‘Who are you?’, it’s tempting to respond with labels, like ‘Asian’, ‘male’, ‘vegetarian’, or ‘student’. These tags are easy to understand, and help others quickly identify us. But such labels only scratch the surface. They tell us about general physical traits, societal roles, or personal choices, but they don’t really dive into the deeper question: What does it mean to be you? Or in general, What does it really mean to be human? Are we just organisms, or is there something more – like a soul, or some other deep basis of our existence? Or are we defined by the relationships we build, our actions, or our potential? Understanding what it means to be human influences how we treat ourselves and others, how we structure society, and how we interact with emerging technologies like AI. This article will take a look at some of the more prominent aspects of being human by outlining key arguments from various philosophers.

Conceptions of Humanity by Vikas Beniwal 2025

© Vikas Beniwal 2025. Please visit his Instagram @Philosophypins

Are We More Than Bodies?

One of the big questions about human nature is whether we’re purely physical beings or whether there’s something immaterial that makes us who we are.

Imagine eating a ripe mango. You perceive its yellow color and taste its sweetness through the subjective experiences of ‘seeing yellow’ and ‘tasting sweetness’. These and other experiences provide fuel for what philosophers since David Chalmers call ‘the hard problem of consciousness’. This asks, ‘How and why do brain processes produce subjective experiences?’ – rather than merely unexperienced mechanical/bodily reactions to stimuli.

Those philosophers who argue for a purely physical explanation – called physicalists or materialists – point to the strong link between our brain states and mental states. Think about how you can be knocked completely unconscious by anaesthetic, or heavily influenced in your thinking by brain injuries or drugs. These examples strongly hint that our mental life is a product of biology, and neuroscience confirms this by showing how our thoughts, emotions, and perceptions correlate to specific brain activities in specific areas of the brain. To some this is compelling evidence that our mental processes are simply complex physical events. But not everyone agrees. Critics argue that trying to reduce consciousness to brain activity alone overlooks something crucial – the very experiences that constitute our minds! These are nothing like the brain activity that they’re correlated with, so how could they be that activity? Moreover, mental contents have no physical properties, so in what meaningful sense could they be said to themselves be physical?

To address the difference, some take a dualist stance, of which there are several variants. Property dualism holds that while everything is made of matter, brains can have both physical and mental properties. Or, on the other hand, substance dualism holds that humans consist of two distinct substances: the material body, and the immaterial mind (usually with the former creating the latter). Some substance dualists, such as René Descartes (1596-1650), go further, and situate the mind in a body-independent immortal soul, such that the soul is the seat of subjective experience.

The concept of the soul has been linked to many metaphysical and ethical concepts. In Hinduism, for example, the concept of soul is connected to the concepts of karma and rebirth. Here the soul is seen as a continuous entity that transmigrates from one body to another. Which type of body it goes into whether human, or otherwise, is based on accumulated karma. This belief provides moral grounding for many people, as virtuous actions will result in favorable outcomes in future lives, while negative actions will lead to future suffering. It’s similar for other uses of the concept of soul, too.

Humans as Rational Beings

One popular idea about what is uniquely human, is that what sets humans apart from the other animals is our ability to think rationally. According to this perspective, the defining characteristic of humanity is the capability for abstract rational thought and the activities this enables, such as language, culture, and ideologies or worldviews.

This view has deep historical roots, and is attributable to eminent philosophers, such as Aristotle, Descartes, and Immanuel Kant. Aristotle for example distinguished humans from other beings by our capacity for logos (roughly, ‘reason’). According to Aristotle, we have a unique rational faculty that other animals lack. Animals have sensitive souls, allowing them to experience sensations, and so represent the world: but humans have both sensitive and calculative (or intellectual) imaginations, which allows them to apprehend what’s morally good through the use of reason. However, animals can’t be truly bad or good in a moral sense, because they lack that rational aspect of thought that makes them morally aware.

This ‘rationalistic’ view supports human exceptionalism – the idea that humans are fundamentally different, and (usually) superior to other forms of life. Descartes notably segregated humanity from other entities, arguing that among all earthly creatures only human beings were sentient. In his view, ‘lower’ animals are nothing but natural machines, devoid of experience. They lack any potential for moral agency, because they lack language, and so the capacity for reason – since for Descartes you need language to have reason, and reason to have a soul, and a soul to have a perceiving mind.

Historically, rationality has also been seen as restricted to specific groups of humans, marginalizing women and lower-status men. For example, Aristotle, who was an aristocrat, believed that some people are permanently limited in their ability to achieve full rationality, particularly women and ‘natural slaves’. He argued that although these groups can receive and act on rational decisions, they lack the full deliberative element of reason and can only follow orders. Nor can they fully grasp the moral good. Feminist philosophers have argued that this kind of reasoning is not about seeking truth, but about upholding patriarchal power structures and reinforcing gender biases. They reasonably contend that such stereotypes limit the potential of and opportunities available to individuals based on their gender. Human exceptionalism is itself linked to anthropocentrism and speciesism the widespread tendency to see humans as being of prime importance and superior to other life. This hierarchical view in turn justifies the domination and subjugation of those deemed ‘less than human’.

Nor is this just a putative description of human nature: it frequently carries normative implications that reinforce existing power structures and privileges. The claim that ‘to be human is to be rational’ is problematic, as it can favor specific genders, races, or classes, and exclude certain groups, such as children and the cognitively impaired, as well as excluding animals, from moral consideration.

Humans as Part of Nature

There is the contrary idea, that humans aren’t special at all – at least not in the way we may think. Naturalistic accounts reintegrate the human subject into the natural world, either as a complex physical system, or perhaps as a part of a panpsychic universe. Panpsychism is the belief that all matter has a form of consciousness. This doesn’t mean that rocks and atoms have minds like ours, but rather that there’s some basic level of consciousness or experience present in all things. These and similar naturalistic perspectives emphasize continuity between humans and other species and reject the idea of a fundamental divide between them. Thus David Hume (1711-76), in his 1739 work A Treatise of Human Nature, suggests, contrary to Descartes, that both humans and animals are capable of thought and reason, differing only in degree, not in kind. Baruch Spinoza (1632-77) goes further, and argues that humans and the rest of the world are part of a single substance – whether one calls it ‘God’ or ‘nature’ – and that everything in the cosmos is governed by the same laws. He also criticizes the tendency to project human-like motives onto nature – such as saying that animals act out of ‘revenge’ – arguing that this anthropocentric lens distorts our understanding.

Even if we do have something unique as humans, such as our capacity for abstract reasoning, that doesn’t necessarily imply our moral superiority, or that we should have different moral treatment. The utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) argued that moral consideration should not be based on the ability to reason but on the capacity to suffer. He famously wrote, “the question is not, ‘can they reason?’ nor ‘can they talk? but, ‘can they suffer?’” (An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1789). Such a perspective broadens the scope of moral consideration to include all sentient beings, not just humans. However, extending moral consideration to all living beings also raises intricate ethical dilemmas of its own. For instance, the agricultural industry is then faced with the ethical implications of practicing animal husbandry, as well as having to address environmental sustainability and food security.

Humans as Part of Society

In his Politics, Aristotle described humans as ‘social animals’. In this view, social interaction is a defining characteristic of our species. We indeed do have an innate propensity to develop complex communities that include systems of law-making and a division of labor.

Other philosophers have offered viewpoints which continue to shape our understanding of human nature and society. Thomas Hobbes (1588-1649) had a somewhat bleak view, believing that humans are driven to form social systems by self-interest, fear, and a desire for power. In Leviathan (1651) he famously described life in a natural (prepolitical) state as “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short”, then argued that society forms out of self-interest – specifically, a shared need for security – rather than, say, out of an inherent altruism. In the same line of reasoning, the child psychologist Burton L. White identifies a ‘selfish’ quality present in children from birth, which manifests through actions he describes as ‘blatantly selfish’.

On the flip side to Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-78) thought humans are naturally good and compassionate, but that society corrupts them. Rousseau imagined the natural state as peaceful, with individuals living in isolation, only coming together as society developed, which he saw as the root of inequality and vice. Karl Marx (1818-83), on the other hand, focused on how social relations shape human nature, arguing that humans are defined by their productive activities and their labor, and that our nature is shaped by the economic and social systems we live in rather than because we have a fixed essence.

Hobbes’ idea of self-interested humans led to his defense of absolute monarchy; Rousseau’s take on our inherent goodness inspired ideas of democracy and individual freedom; and Marx’s laborer provides critiques of capitalism. Each of these perspectives highlight different aspects of what it means to be human and of the role of society in shaping human behavior.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein reimagined by Venantius (2025) for this article.

Creating New Humans

New technologies are pushing us to rethink what it means to be human, and genetic engineering and artificial intelligence challenge traditional notions. For example, genetic modification could enhance physical or cognitive traits in humans – but it also blurs the lines of what constitutes a ‘natural’ human. Such modifications could lead to discrimination and inequality if not carefully regulated.

Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818) highlights this dilemma. Frankenstein’s creature, abandoned by his creator, was ostracized for his appearance and unnatural genesis. This demonstrates a potential prejudice against genetically modified children. Humans, if defined by having a natural biological blueprint, might exclude such children, and their rights.

Another worry is of creating artificial intelligence with human-like consciousness or even surpassing human cognitive abilities. If AI systems develop self-awareness, where do we draw the moral line between human and machine?

Transhumanism, which explores the merging of humans and technology, proposes that we might one day upload our consciousness to digital platforms, and thereby overcome our biological limitations, even death.

A thought experiment by the philosopher Sidney Shoemaker offers a perspective on the continuity of identity in such an upload. In his scenario, a machine scans and erases personal information from one brain and transfers it into another brain. If psychological continuity confers personal identity, then the individual resulting from this transfer would be considered to be the person from the original brain. But here’s a catch: let’s suppose that while your brain is being scanned and a digital version of ‘you’ is being created to be transferred into the new brain, there’s a moment when your mental properties – your thoughts, feelings, and experiences – aren’t active at all. So, have you just died? And are you just about to be resurrected – or are they just making a copy of you? The situation highlights the complex metaphysical and ethical implications of uploading minds.

Given this sort of problem, among many others, many psychological-continuity proponents of personal identity rule out your moving onto (or via) a computer. They may further assert that for personal identity to truly persist, there needs to be an uninterrupted physical basis for your mental properties. The idea of uploading our minds into a digital hub also presents many ethical challenges around questions such as, if the process is successful, what becomes of our original physical body and brain? Then there’s the question of the rights and responsibilities of these digital beings. And how do we handle the creation, and potential termination, of digital life? These are deep moral questions that need careful thought from both philosophers and computer scientists.

In a world where technology is rapidly evolving, we can see that the ongoing inquiry into human nature is more important than ever. As we navigate the ethical and political challenges of the future, it’s not just about finding answers, but also about asking the right questions.

© Vikas Beniwal 2025

Vikas Beniwal is currently pursuing an MA in Philosophy at the University of Mississippi.

• I wish to thank Prof. Eric Olson for helping me navigate the literature on this theme, as well as Prof. Akshay Gupta and my friend Evan for their valuable feedback.