Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Perfect Days

Thomas E. Wartenberg focuses on a path to happiness.

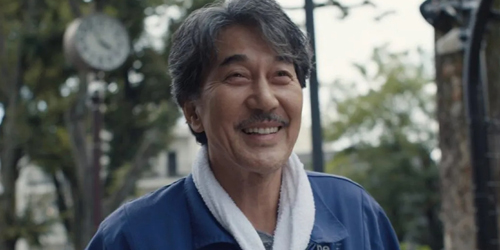

Hirayama (Kôji Yakusho), the Japanese toilet cleaner protagonist of Wim Wenders’ 2023 Academy Award Winning Film Perfect Days, is the anti-Sisyphus.

Sisyphus, you may recall, is the hero of Albert Camus’ philosophical essay, The Myth of Sisyphus (1942). According to the Ancient Greek myth Camus draws up on, Sisyphus was condemned by Zeus to rolling a huge stone up a hill every day, only to have it roll back down to the bottom of the hill each evening. Annoying, right?

For Camus, Sisyphus’s unflagging yet futile attempts to hoist that rock to the summit represents the essence of human life, which is its absurdity. For Camus, life’s absurdity is the result of a conflict between our need for meaning and the world’s indifference to us. ‘Absurdity’ signifies our collective inability to find a way to make our lives meaningful.

Having to face a difficult futile task on a daily basis only to see all of your efforts amount to naught might make you depressed, even suicidal. Yet Camus does not draw that obvious conclusion from his account of the absurdity of life. Surprisingly, Camus characterizes Sisyphus as the absurd hero par excellence, and concludes his essay with a startling sentence: “We must imagine Sisyphus happy.” This assertion stems from Camus’ view of Sisyphus as scorning the gods and the fate they’ve assigned him. Sisyphus’s contempt results in his triumph over them, for, as Camus says, “there is no fate that can’t be surmounted by scorn.” He asks us to imagine the scornful Sisyphus raising his fist in triumph at Zeus as he watches his rock tumble back down the hill, forcing him to resume his thankless task.

Film images © DCM/Bitters End 2023

Hirayama’s days are portrayed in Perfect Days as similarly occupied by unending repetitive tasks, even if they do not demand the same toil. From the moment he rises, stores his tatami (floor mat) and futon neatly in a corner, and goes to trim his beard and brush his teeth, Hirayama’s days are filled with routine chores. What’s surprising is that he doesn’t resent having to do such mundane things continually; instead, he pursues them in an almost ritualistic manner. As he leaves his sparsely furnished home (the only furnishing we see aside from his mattress is a bookshelf of second-hand books) he always stops at the machine that dispenses the can of coffee he drinks as he drives his van to work cleaning toilets in Tokyo. His days are filled with toilet cleaning – even as people barge past his sign that says that the toilets are closed for cleaning. As they use the toilets, he waits patiently until he can resume the performance of his task.

Even though Tokyo features high tech, beautifully constructed toilets – the film originated in an attempt to publicize them – cleaning toilets is about the lowliest job imaginable, something most of us would abhor having to do; and people who do it for a living are regarded as low class by many. The people using the toilets often pass Hirayama without even noticing him and his deferential behavior as they disrupt his work. One young mother goes so far as to completely ignore him even though he rescued her young child from being trapped in a toilet.

It's not only strangers who treat Hirayama with disdain. His own estranged sister, Keiko (Yumi Asô), expresses her contempt for his work when she comes to his apartment to pick up her daughter Niko (Arisa Nakano), who has run away from home and come to stay with him. “Do you really clean toilets?” she asks him in astonishment, and with not an insignificant amount of disgust.

Despite these peoples’ attitudes, Hirayama takes great pride in his job. He pays close attention to the cleanliness of the toilets, going so far as to use a mirror on a long stem to examine the undersides of the toilets to be sure they’re spotless. His devotion to his work even puzzles his co-worker, Takashi (Tokio Emoto), who asks him how he can be so committed to doing a perfect job when the toilets will be soiled soon thereafter. Why clean them so fastidiously when the next person who uses them will hardly notice their cleanliness, and will likely leave them filthy?

Hirayama’s joyful performance of the mundane and sometimes disgusting tasks he performs stems from the attitude he maintains throughout his day. Unlike Sisyphus, Hirayama brings focused attention to every aspect of his life. Each day, as he emerges from his house, he stops and looks at the sky and trees. A winning smile emerges on his face as he then proceeds to the business of living his life.

Wenders repeatedly films Hirayama as he proceeds on his daily routine. On most days, nothing happens to disrupt it: waking when the old woman who sweeps the street comes by; folding up his bedding; shaving and brushing his teeth; emerging from the house; buying his coffee; driving to his job; and so on. Most days, Hirayama has almost no human contact, refusing to engage in banal conversation with his co-worker Takashi, and not speaking to the chef who serves him dinner, and not exchanging more than a perfunctory comment to the barkeep, ‘Mother’ (Yuriko Kawasaki), who clearly likes him.

An unusual feature of Hirayama’s life is his avoidance of digital devices. For example, when he has to call his sister to tell her that her daughter’s with him, he has to use a payphone; and in his van he listens to cassette tapes with songs from the 60s and 70s, such as Van Morrison’s Brown-Eyed Girl and the Velvet Underground’s Pale Blue Eyes. He’s so clueless about digital media that he even asks his niece where Spotify is, thinking it to be a physical store. To show how unusual Hirayama’s anti-digital stance is, the film shows a number of people riding in his van who are not able to manage the simple task of putting a cassette into the audio system, so unfamiliar are they with the outmoded technology.

As we repeatedly watch Hirayama performing the tasks that constitute his daily routine, we slowly come to realize that his simple life is filled with great joy. What’s particularly striking is the pleasure he takes in looking at and photographing the large trees in the park where he eats his lunch every day. Wenders uses point-of-view shots to convey what Hirayama sees as he looks up at the trees. The Japanese word, komorebi (which was the original title of the film) means ‘sunlight leaking through trees’, and Hirayama marvels at the beauty of that phenomenon on a daily basis. Few of us would take the time to sit on a park bench each day, look up at the komorebi, and record what we see in a photograph. But Hirayama has a profound connection to the trees, and, in fact, all of the world, and keeps a photographic record of the changes he sees, using a simple film camera to do so.

When Keiko arrives in a chauffeur-driven limousine to pick up Niko, we become aware that Hirayama has chosen to live as he does. He came from an upper-class family, and his father, now dying, was apparently furious over Hirayama’s rejection of the life he was supposed to live. Keiko cannot understand how Hirayama can live and work in the manner he does, either. But Niko is more observant, and spends enough time with Hirayama to understand what his life offers him, and, indeed, that his simple life is preferable to the life she lives with her mother despite its material rewards.

Hirayama’s ability to experience joy in mundanity is a result of his being completely present to the world and everything it contains. The notion of being present – also known as mindfulness – means focusing your mind on nothing other than your current experience. You don’t think about what needs to get done, but instead are only aware of the sensations present to your consciousness in the moment, no matter what you are doing. Hirayama is portrayed as nearly always present. Indeed, his limiting his life to only the barest necessities aside from the books he reads is intended to eliminate everything that would distract him and keep him from being present.

The joy that being present unleashes in Hirayama forms the counterweight to the scorn that Camus emphasizes in his account of Sisyphus. The toilet cleaner’s motto might be this implicit response to Sisyphus: “There is no fate that cannot be overcome through presence.”

The philosophical importance of Perfect Days lies in its illustration that a life lived with a focus on the present is able to overcome the feeling that life is absurd. This does not involve rebelling in defiance at the absurdity of the terms we have been given for living our lives, which is the response that Camus suggested. Rather, a person who is fully present to everything he does and experiences is shown to be contented with their life even though, or, better, because there is no big concern to fill it with meaning. With concerns come distractions, the enemy of presence and mindfulness. Meaning, we learn from Wenders’ film and Hirayama’s example, is not something that one gains through projects and plans, but simply by acts of conscious awareness. Such a different, and more successful way to live, than with one fist defiantly raised to the heavens.

© Thomas E. Wartenberg 2025

Thomas E. Wartenberg is film editor of Philosophy Now. His latest book, Thoughtful Cinema: Illustrating Philosophy Through Film, will be published by Oxford University Press later this year.