Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Happiness

The Good Life Paradox

Matthew Hammerton points out that a meaningful life and a life that goes well for you might not be the same thing.

Picture two people on their deathbeds. The first lived comfortably, surrounded by loving family and friends, enjoying diverse pleasures and achievements throughout a long life. The second dedicated herself entirely to fighting injustice, achieving remarkable social change, but at great personal cost. Who lived the better life?

Your answer might depend on what you mean by ‘better’. Philosophers have long recognized that when we call a life ‘good’ we can mean different things. So we could be talking about a life’s moral goodness – how virtuous the person was – or its prudential goodness – how well the life went for the person living it. But there’s a third dimension we often overlook: how meaningful the life was. This gives us three distinct questions we can ask about any life: 1. Was it morally good? 2. Did it go well for the person living it? 3. Was it meaningful?

These questions pull in different directions. A morally exemplary life might involve suffering for others’ sake, making it less prudentially good. A meaningful life might also require sacrifices that reduce personal well-being. Understanding these tensions can help us navigate our choices about how to live.

Is Meaning Just Well-Being in Disguise?

Here’s where things get philosophically interesting. When we examine what makes lives meaningful, we find striking similarities to what makes lives go well. Theories of both meaning and well-being come in subjective and objective varieties, appealing to overlapping goods, such as love, knowledge, achievement, and aesthetic experience. This raises an uncomfortable question: Is ‘meaning in life’ just another way of talking about well-being? Perhaps then when someone complains that their life lacks meaning, they’re really just saying it lacks important components of well-being.

Consider the parallels. Subjective theories of well-being say your life goes well when you’re satisfied, your desires are fulfilled, or you experience pleasure. Some theories of meaning make identical claims about meaningfulness. Objective theories of well-being point to goods like knowledge, love, and achievement as being valuable for the person who has them. Theories of meaning point to exactly the same goods as sources of life’s significance.

This similarity is puzzling. If meaning and well-being are genuinely distinct, why do their theories look so alike? The most obvious explanation is that they’re actually the same thing – that ‘meaning’ is just a fancy way of talking about certain aspects of well-being.

Three Failed Defenses

Philosophers have tried several strategies to preserve meaning as a distinct category, but none quite succeed.

Strategy 1: Different Types of Goods

Some argue that well-being concerns only subjective goods such as pleasure, while meaning concerns only objective goods like achievement. But this seems untenable. If you admit that achievement is valuable, then isn’t it bad for you if your life lacks it?

Imagine some mad scientists trying an experiment out on you. While you sleep, they hook you up to a Matrix-like experience machine without you realising it, then feed you preprogrammed experiences that resemble the kinds of experiences you would have had anyway if you’d lived your life in the real world. They leave you in the machine for the rest of your life. From the inside, nothing seems amiss; your subjective state is unchanged. Yet surely they have harmed you. By denying you a connection to reality – genuine achievements, real relationships with real loved ones – they have caused your life to go less well for you.

Strategy 2: Pleasure Doesn’t Matter for Meaning

Another approach claims that while pleasure contributes to well-being, it never directly contributes to meaning. Compare two equally lazy lives spent watching sitcoms and eating junk food. Suppose that one of these lives is more pleasurable than the other. From the perspective of well-being, the more pleasurable life seems the better one to live. Yet from the perspective of meaning, both lives seem equally meaningless.

The problem here is that even if this argument works, it only shows that meaning differs from the hedonic (pleasure-related) aspects of well-being. The non-hedonic components still overlap completely, and thus ‘meaning’ is just a fancy way of talking about these other aspects of well-being.

Strategy 3: Different Consequences

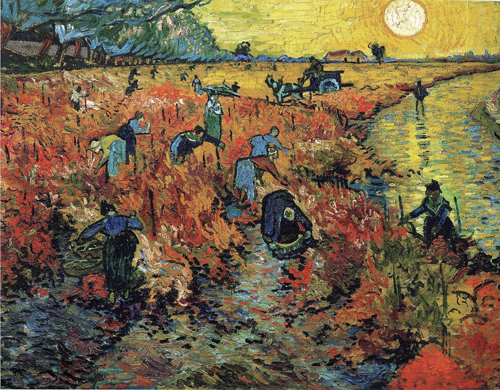

Some argue that certain things add meaning without enhancing well-being. Consider a freedom fighter who dies heroically for independence. Her sacrifice seems profoundly meaningful, yet surely she would have been better off surviving to enjoy more of life’s goods? Or think of Vincent van Gogh, whose posthumous artistic recognition seems to have added meaning to his life retrospectively (he only sold one painting while he was alive). Yet how could any events after his death improve his personal welfare? These cases initially appear to show meaning and well-being coming apart.

However, theories of well-being can accommodate both examples. If the freedom fighter’s deepest desire – stronger than her desires for comfort or longevity – is to advance her cause, then desire-satisfaction theories say sacrificing herself advances her well-being. And, objective theories that include moral excellence would say heroic self-sacrifice significantly boosts the moral excellence in her life also thus enhancing well-being. Similarly, if van Gogh wanted his art appreciated, then its eventual recognition satisfied this desire even posthumously; while objective theories can treat his lasting artistic influence as an achievement that posthumous recognition helped complete.

Artwork © Simon Ellinas 2025 Please visit caricatures.org.uk

A New Solution: Different Ways of Adding Up

Here’s a fresh approach that preserves meaning as genuinely distinct from well-being while explaining their similarities. Both meaning and well-being might arise from the same basic goods – love, knowledge, achievement, moral excellence, aesthetic experience, and so on – but they differ in how these goods combine to produce value. The ingredients might be the same, but the recipes are different. For well-being, what matters is not just the total quantity of good things in your life, but also their balance. Consider someone who becomes an exceptional moral leader in her community but has little time for personal relationships, intellectual pursuits, or aesthetic appreciation. Now imagine someone else who lives a well-rounded but relatively unexceptional life, achieving moderate success across all these domains. Even if both lives contain exactly the same total quantity of good, the balanced life intuitively seems better for the person living it.

We can push this idea further: imagine a lopsided life focused solely on intellectual achievement that contains 100 units of good, versus a well-balanced life containing knowledge, relationships, aesthetic appreciation, and moral development, that totals only 98 units. Despite having slightly less total good, wouldn’t the balanced life still be better for the person living it?

For meaning, however, balance seems irrelevant. What makes a life meaningful under this view is the sheer quantity of valuable goods it contains, regardless of how they’re distributed. The more total good your life creates or connects with, the more significant and impactful, and thus meaningful, it becomes. Consider Leonardo da Vinci, whose life spanned art, science, engineering, and philosophy with remarkable balance. Now compare him to someone like Albert Einstein, whose life was far more focused on physics and mathematics. Both lived extraordinarily meaningful lives, but Leonardo’s balance doesn’t seem to add extra meaning beyond what his total achievements provided. His well-rounded achievements might have made his life go better for him, but the meaning came from the sheer quantity of valuable goods his life contained.

This distinction helps explain paradigmatically meaningful lives. Think of figures like Gandhi, Marie Curie, or Pablo Picasso. All lived remarkably lopsided lives, intensely focused on a narrow range of goods rather than pursuing well-rounded achievement. Their meaning came from the extraordinary quantities of goods – virtue, knowledge, or artistic beauty – they realized, not from a balance among different goods.

Darwin’s Dilemma & Parfit’s Choice

Charles Darwin provides a poignant illustration of how meaning and well-being can pull apart. Darwin’s single-minded focus on scientific work led to extraordinary discoveries that gave his life tremendous meaning. But Darwin himself later regretted this choice, telling his daughter that he wished he had ‘not let his mind go to rot so’ by neglecting poetry and other pursuits that once brought him joy.

Who’s right: Darwin, or his admirers who celebrate his focused life? I would say both are right, but in different ways. From the perspective of meaning, Darwin’s choice was vindicated. His concentrated effort produced more total good than a more balanced approach likely would have done. But from the perspective of well-being, Darwin’s self-assessment may well be true. A more balanced life, with an interest in biology yet with much more time for other pursuits, might have gone better for him personally, even if he would have achieved less.

Consider also Derek Parfit (1942-2017), arguably the most influential moral philosopher of his generation. Early in life, Parfit showed exceptional talent across multiple areas – he excelled academically, edited Oxford’s leading student magazine, played jazz trumpet, wrote poetry, and engaged in student politics. He could have lived a richly varied life of broad achievement. But instead, Parfit chose extreme specialization, becoming almost monomaniacal about philosophy. He stopped taking vacations, abandoned his other interests, and lived increasingly eccentrically—reading philosophy while brushing his teeth and even eating the same food every day to minimize preparation time—all to maximize the hours he could devote to philosophy. By most measures, this choice produced an extraordinarily meaningful life – his groundbreaking ideas have reshaped moral philosophy. But was it the best life for Parfit himself?

Many of us would find something disturbing about living so lopsidedly, even knowing it would let us make a greater mark on the world. This suggests that while Parfit’s choice maximized meaning (total good produced), it may not have maximized his personal well-being (balanced good experienced).

This kind of trade-off appears throughout human life, from career choices to relationships to hobbies. Sometimes we must choose between pursuing greater total good (that is, meaning) or a better-balanced distribution of goods (well-being). Understanding this tension can help us make more thoughtful decisions about how to live.

The Red Vineyard by Vincent Van Gogh, 4th November 1888. The only painting Van Gogh is known to have sold in his lifetime.

Living with the Tension

This analysis doesn’t resolve the fundamental tension between meaning and well-being, but it does clarify it. Sometimes they align: we can still pursue meaning while maintaining good balance in our lives. But often they pull apart, forcing us to choose.

The key insight is that both matter, but in different ways. Meaning speaks to our desire to make a significant impact, to connect with or create genuine value in the world; well-being speaks to our desire for lives that go well for us as the people living them. Some people reasonably prioritize meaning, accepting personal costs for the sake of greater impact. Others reasonably prioritize well-being, seeking rich, balanced lives even if this means less total achievement. But neither is automatically more important than the other. Most of us navigate between these poles, making different choices at different times.

Understanding this distinction won’t solve the puzzle of how to live, but it can help us think more clearly about what we’re choosing between. When we feel torn between pursuing our passion intensively or maintaining balance in our lives, we might be feeling the pull of meaning against well-being. When we wonder whether to make personal sacrifices for a cause we believe in, we might be weighing meaning against well-being.

This analysis has concrete implications. It suggests that people asking ‘What should I do with my life?’ are often implicitly choosing between two different kinds of value. Do you want to maximize your positive impact on the world, even if this requires sacrificing balance and personal satisfaction? Or do you want a life that goes well for you, even if this means less achievement?

There’s wisdom in both approaches. The meaning-seeker who sacrifices personal comfort for greater impact deserves our respect and admiration. But so does the person who chooses a balanced life of moderate achievement across many domains. Both are responding to genuine sources of value – just different ones.

Perhaps the deepest insight here is that the ancient question ‘How should I live?’ doesn’t have a single answer because it’s really two questions: ‘How can I live meaningfully?’ and ‘How can I live well?’ Sometimes they point in the same direction – but when they don’t, we have to choose – and that choice reveals what kind of value we care most deeply about.

The good news is that understanding this choice can help us make it more wisely, with fuller awareness of what we’re gaining and what we’re giving up. In a world that often presents us with false dichotomies, recognizing the genuine tension between meaning and well-being, and the legitimacy of both, might itself be a form of wisdom.

© Matthew Hammerton 2025

Matthew Hammerton is Associate Professor in Philosophy at the School of Social Sciences, Singapore Management University.