Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Fiction

René Descartes Loses His Phone

Judah Crow follows Descartes as he seeks that which one must have always.

I remember when René Descartes lost his cell phone. He’d come up to visit us in Port Townsend, Washington, where we’d been living for a few years. Descartes liked the quiet of the town: he liked seeing deer in the street instead of cars, and that the few cars were driven by grayhairs, who drive very slowly. He also liked the spring rain – which was frankly driving me crazy after a long, gloomy winter. But then he lost his phone.

“But you hate your phone,” I said. He was always complaining about it.

We were at the breakfast table. Descartes was still getting used to modern American clothes. Like all the other guys in Port Townsend, he was wearing black Carhartts and a fleece sweater. He was trying to hang on to his lace ruff, though – so he couldn’t wear a hoodie, as there’s no way to combine a hood and the ruff. He’d started washing his hair every Saturday, and it looked way better; but the ruff just made him look like a clown.

“The cellular, it is something terrible,” Descartes replied. “But in this world, to be without such a thing… it is, in effect, impossible.”

He had been staying with me and Molly for a couple of weeks. He said he was looking for an apartment, but he didn’t have a job, and he didn’t have any money that I could see, so we let him use our office as his bedroom. It was okay with me. He was a good house guest. Except he never went to sleep. If I woke up at two in the morning, Descartes would still be creeping around the house, using the bathroom, or getting himself a bowl of cereal.

Anyway, he couldn’t stop fussing about that phone. He said: “Ask me, if you please, in which place I was, when I held it last.”

I said: “Why don’t I just call your number? Then you’d hear your phone ring, and you’d know where it is.”

His face fell. “But no. The sound – it is execrable. I turn this off, always.”

“You leave the ringer off? How you do you know when somebody’s calling you?”

“If there is someone with whom I wish to converse, then I should call that person. Yes. But now you must help me. Ask me, if you please, where I was, and at what time, when I had my phone the last time.”

It sounded so poetic that way, like he wanted to write a sad song about his last time holding something he loved. But he meant it literally: he wanted me to literally ask the question. He said he’d remember better if the question came from someone else. Descartes is a very smart guy, but all the time I’ve known him he’s always had funny ideas. So I asked him.

“It was yesterday,” he answered, squeezing his black eyebrows together, “Or it was the day before yesterday, when we were in your car, perhaps. We were en route to the hardware store.”

We searched the car. Nothing. He had already turned the whole office upside down. He’d also walked all around the yard, in case he’d dropped the phone while he was mowing the lawn, though that was back on Saturday.

I took Descartes down to Water Street for sandwiches. I said, “You can use my phone if you want to call somebody.”

Descartes grimaced, and responded, “It is not that I wish to call some person! Who is it that I should call? There is nobody. It is a question of the cellular, which one must have always.” That’s right – the phone he hated.

To cheer him up I suggested we stop at the bookstore.

He went straight to the Philosophy section, of course. He was sad to see that the store had only one of his books – an old Penguin Classics edition of his Meditations – while it had any number of expensive hardbacks of a guy called ‘Foucault’ – down by the floor. Descartes didn’t like having to crouch on the floor to see them.

“He is extraordinarily popular,” Descartes grumbled, as we headed home, “this philosopher Foucault. Why is it that his thoughts find such favor? I opened these books of his. I could not understand even one sentence fully.”

“I wondered the same thing. I flipped through one of his books too. I really have no idea what he’s talking about.”

“He does not write with clarity and distinctiveness!” declared Descartes. He rolled down his window and looked at the rain.

“Maybe he’s writing as clear as he can, though. About things which are just hard to explain?”

“That is impossible,” said Descartes. “If one can hold a clear thought in mind, then one can express it in words which are framed with clarity.”

He unbuttoned his ruff from the back. It had got wet in the rain and was dripping water down the back of his neck. Now he looked like a carpenter, or maybe a guy who used to work on boats – who happened to have a wet lace ruff in his lap, like a small white dog.

He was taking the phone loss badly. He couldn’t stop fretting about it. “The essence of the matter,” he said to Molly after dinner, as they were washing dishes, “the essence is – the phone must be in some place.”

“Are we sure that’s right?” asked Molly. She liked Descartes, but she wasn’t used to his funny ideas .

“But of course,” said Descartes. “It is certain. It is most certain. The cellular is a physical thing, so it is in one place, one place alone. If I should look in that place, then I shall find it. If I fail to look in that place, I shall not find it.”

Molly was too polite to laugh: “You mean, your phone is in some place, whether you ever find it or not? Well! I never thought of it that way.”

She looked up at me, then, smiling. She was wearing yellow rubber dish gloves. Descartes was wearing the pink ones, because they fit his hands.

Molly looked happy. She liked my crazy friend Descartes. To try to cheer him up she told him: “You know, maybe the reason the bookstore has so many books by Foucault, and only one book of yours, is that nobody wants the Foucault books, so they’re still on the shelf? But people buy your books, and take them home! Since they can only be one place at a time.” She laughed then, her voice going up and down the scale as she laughed. I loved her for that. I don’t know why. It had been a long time since I’d remembered how much I love Molly.

After dinner Molly and I did the Wordle together. Descartes couldn’t sit still. He took the cushions off the couch to see whether the phone had slipped down between them. “But it is idiotic,” he growled. “I have looked there already. More than one time! There is no reason to look again. I could not stop myself. I am like a child.”

“Did you check all your pockets in all your clothing?”

“But yes, certainly.”

“Did you check back at the hardware store?”

“I have asked the manager, face to face.” He was now digging through the shoes at the bottom of the hall closet.

“Sorry it’s so dark in there Descartes. I meant to get a new bulb. Maybe try looking in the daytime, when there’s more light. Why don’t you look in the laundry room?”

“My cellular could not be in the laundry room,” said Descartes, “because I myself have not been in the laundry room in two weeks. For what reason should I look in the laundry room?”

“Because more light,” Molly and I both said at the same time. She said “Jinx!” and then we both guessed the Wordle at the same moment. It wasn’t ‘LIGHT’, but it was ‘RIGHT’.

On Tuesday I called Molly from Jonno’s Auto Body. I was getting a dent hammered out of the Civic. I said: “Guess what. I found Descartes’ phone! It was under the seat in the car.”

Molly laughed. She said: “Well guess what. I found a phone too! It was in the laundry room, on the shelf. He must’ve been down there for some reason.”

“Poor guy. Now he has two phones to hate.”

Finding it twice – at the same time! It seemed lucky, like seeing a rainbow. But that night, Descartes burst in, a little late for dinner, carrying something in his hand that looked like a little box of mud. He said, “The mystery, now it is finished. I have found the cellular, though alas it has gone entirely to ruin. It was in the mud at the frog pond. I must surmise that it fell from my pocket, at the time we were visiting there after church last Sunday.”

Molly and I tried in vain to hold back our laughter as we told him we had a surprise, then we showed him the phones we’d found. Now not one phone, but three! Wouldn’t you just know it? We put them all side by side on the kitchen counter and ate our tacos.

After dinner Descartes stared at the three phones for a long time, without saying anything. He looked grumpy.

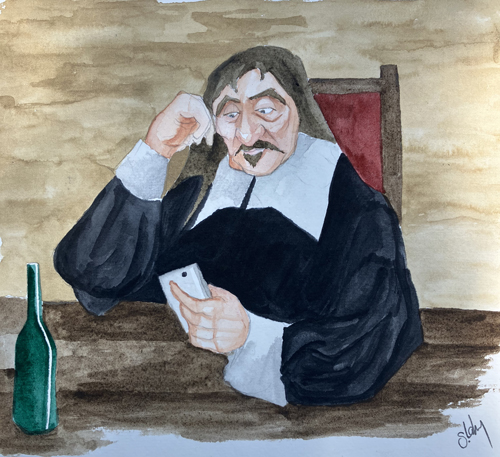

René Descartes by Stephen Lahey 2025

Molly asked: “Everything okay?”

“Which one is authentic? Only one can be mine, truly.” He looked like he was still chewing dinner but there wasn’t anything in his mouth. He was working himself into a crappy mood.

Molly said: “Well, if only one can be right, which one looks the way you remember?” But Descartes said he couldn’t remember the details of his phone, which he hated. He said they all looked alike to him.

Molly called his number, but none of the phones rang. The muddy one was trashed, so that was no surprise. Descartes couldn’t remember a password for the phone from under the car seat. The phone from the laundry room didn’t need a password. It had a few phone numbers stored in it: my number, and Molly’s, and numbers from a few other people none of us knew. But it didn’t ring when Molly called him.

The next day Descartes was up at dawn, sitting at the kitchen table, drinking a pot of chamomile tea, and waiting for me and Molly to wake up. He was dressed in his old clothes from the first day he’d come to town: a shabby cloak of black velvet, the lace ruff, little pointed shoes with buckles. His hair was greased down again. He even smelled the way he’d smelled at first – like neither he nor his clothes had been washed for some while. He was waiting for us to take him to the bus station. His black leather satchel was at the door, no doubt packed up with yellow papers scratched with words and diagrams.

Molly drove him down to the station. When they were gone, I noticed that he’d left all three phones behind. I think they’re still in the closet, somewhere.

© Judah Crow 2025

Judah Crow is … what?