Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Digital Philosophy

Rescuing Mind from the Machines

Vincent J. Carchidi agrees with Descartes and friends that our ability to use language creatively distinguishes our minds from computers.

The study of artificial intelligence was originally conceived partly as an effort to make sense of the human mind. That is to say, the pursuit of practical computing machines ran parallel to an interest in computing as a model of human cognition. This was present from the start in Alan Turing’s 1950 essay ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’. Indeed, some scholars argue that the field of AI moved from a multidisciplinary effort to simulate the workings of the human mind, to a project of literally building human-like intelligence into machines.

The shift can be exaggerated; after all, figures such as John von Neumann spoke even in the twentieth century of an approaching technological ‘singularity’. That said, the shift towards desiring human-like artificial intelligence is real, and it has resulted in an ever-intensifying trend that in fact devalues the human mind. Indeed, a routine association of computational models with biological minds in part prompted this warning in Nature Machine Intelligence in December 2024: “The era of machines as deterministic, predictable, and boring objects of fixed structure is coming to an end.” One implication of all this is: we need clarity on the relation between engineered machines like AI systems and biological beings like us, and we need it now.

Descartes’ Turing Test

AI poses anew a centuries-old challenge: What, if anything, distinguishes the human mind from the workings of a machine? This problem traces back at least to René Descartes (1596-1650), who put it as follows: Suppose one comes across a creature that bears the outward appearance of a human being and moves through the world like a human. How are we to determine whether this being has a soul – or a mind – like ours?

Descartes’ problem of other minds reveals that our current dilemma in understanding them is not new, and that this whole topic has deep ties with machine history. The Large Language Models (LLMs) of recent fascination are merely the latest iteration of this challenge.

The cultural influences on Descartes’ thought help us understand why he posed this problem – why he thought it so important to distinguish humans from machines. For many Christians in Europe even before Descartes, machines were a common part of life. As Jessica Riskin details in The Restless Clock (2016), life-like automata of various kinds – humans, animals, angels – were constructed for use in churches and cathedral clocks. Such machines could have an active presence in the world, displaying, as Riskin puts it, ’a vital and even a divine agency.” This perception of agency was thus both attributed both to living beings and to (some) machines.

However, in the 16th century the Reformation, triggered a shift in how the natural world was perceived. In the eyes of religious reformers, machines became, as Riskin elaborates, ‘empty of spirit’ by virtue of their composition merely of mechanical parts. Furthermore, the ‘mechanical philosophy’ – the idea that all of existence’s diverse phenomena can be accounted for as though the world were a complex machine – was gaining prominence. The natural world’s mechanical properties were separated from divinity and agency; thus the life-like automata that once accompanied Christian liturgies were no longer in possession of spirit. Their construction from artificial components made them mere machines lacking agency.

Human uniqueness required something beyond the mere complex organization of matter. So although Descartes, according to Philip Ball, “set out a view of the human body as a wondrous mechanism of pumps, bellows, levers, and cables” (How Life Works, 2023), these components are for Descartes, “animated by the divinely granted rational soul”, which is connected to but independent of the body.

The metaphysical rubber begins hitting the road for Descartes at roughly this juncture. He poses his problem of other minds in his 1637 book Discourse on Method thus: Imagine observing a mechanical body that exhibits all of the outward appearances of a human being – it appears to have the same skeletal and muscular structure, the same layout of veins and arteries, and it exercises the same movements of the body as any human might. How, Descartes asks, can we distinguish between this body and an actual human being, if each is ultimately the product of a complex network of mechanical components ? He then argues they can be distinguished through ‘’two most certain tests”, one of which is a language test. Descartes argues that how human beings use language has a distinctive character, inexplicable in purely mechanical terms and the detection of this distinctive character indicates that we are not observing a machine, but a creature with a mind like our own:

“Of these [tests] the first is that they could never use words or other signs arranged in such a manner as is competent to us in order to declare our thoughts to others : for we may easily conceive a machine to be so constructed that it emits vocables, and even that it emits some correspondent to the action upon it of external objects which cause a change in its organs… but not that it should arrange them variously so as appositely to reply to what is said in its presence, as men of the lowest grade of intellect can do” (Emphases added).

So, according to Descartes, one may judge that a being possesses a mind like ours if its language-use meets certain criteria. One is that the subject’s speech is intelligible (‘competent to us’). Another is that it uses speech to express its thoughts (‘declare’ them). The third is that it combines words in an appropriate fashion (‘arrange them variously’ as ‘appositely to reply’). Finally, they should do so habitually, without specialized intelligence (‘as men of the lowest grade of intellect can do’). Descartes also rules out two language conditions as insufficient for inferring the presence of a reasoning mind: the mere output of words (‘emits vocables’), and the mere output of words as a direct result of contact with external stimuli (‘correspondent to the action upon it’). Also, on Riskin’s reading of the history of automata, it was the ‘limitlessness of interactive language’ that stopped a physical mechanism from reproducing human linguistic ability. So ordinary language use, therefore, was granted the status of non-mechanical – attributed instead to, as Descartes would put it, a ‘rational soul’.

Descartes’ initial remarks on the language test were extended by his followers, including Géraud de Cordemoy. Yet, this problem of infinite linguistic generativity from a finite physical being stymied further inquiry until long after the mechanical philosophy’s demise.

Artificial Intelligence Eye Mohamedgu123 Creative Commons 4

Computing Language Computability

Alan Turing’s (1912-54) genius was to prove it a possibility: “It is possible to invent a single machine which can be used to compute any computable sequence” (‘On Computable Numbers’). He demonstrated that in principle a single ‘Turing machine’, with a fixed structure, could carry out every computation that can be carried out by any machine. Put simply: infinite generation from finite means is possible. The establishment of general computability theory in the early twentieth century gave us the tools to study this possibility.

Linguists in the early-to-mid twentieth century reformulated Descartes’ problem along lines enabled by computability theory. But just as Descartes first articulated the language test within a problematic framework – the mechanical philosophy from which human language use was exempted – computability theory re-shaped the problem of artificial language use in ways that similarly disturb our efforts at explanation. For computability theory has its own limits. For instance, notice that the study of a finite biological system capable of infinite generativity says nothing about the actual use of the system. So computability theory provides no direct insight into ordinary language use – the original Cartesian problem. Thus, a distinction between competence and performance is drawn: a person might be able to speak with infinitely more variety and facility than they actually do speak. This distinction is crucial. The tools that enable us to study the infinite generativity of a finite biological system, residing within the human brain’s language faculty, are suited only to the task of characterizing the system. The use of this ability in actual linguistic production is another matter entirely. Today, this ‘creative’ aspect of language use occupies ‘linguistic performance’ inquiry. Contemporary linguists and philosophers have formalized Descartes’ and Cordemoy’s observations about human linguistic possibility into three conditions:

Stimulus-Freedom: Humans can produce new expressions that lack any one-to-one relationship with their environments. Generally, stimuli in a human’s local environment appear to elicit utterances, but not cause them. If human language use is not affixed in some determinate, predictable fashion to stimuli, then language use is not directly caused by situations. Among other things, this means that meaningful expressions can be generated about environments far-removed from the local context in which the person speaks; or even about imaginary contexts. The contrast with animal communication is striking here. For animals, communication is restricted to the local context of its use. Human language use is, in sharp contrast, detachable: a pillar of the human intellect may be the ability to detach oneself from the circumstances in which cognitive resources are deployed without reliance on stimuli to do so. In other words, we can think for ourselves.

Unboundedness: Human language use is not confined to a pre-sorted list of words, phrases, or sentences (as it is with LLMs). Instead, there’s no fixed set of utterances humans can produce. This is the infinite productivity of human language – the unlimited combination and re-combination of finite elements into new forms that convey new, independent meanings.

Appropriateness to Circumstance: That human language use is stimulus-free can be revealing when we reflect that utterances are routinely appropriate to the situations in which they are made and coherent to others who hear them. If human language use is both stimulus-free and not caused by situations, this means its relation to one’s environment must be the more obscure relation of appropriateness. Indeed, language use “is recognized as appropriate by other participants in the discourse situation who might have reacted in similar ways and whose thoughts, evoked by this discourse, correspond to those of the speaker” (Language and Problems of Knowledge, Noam Chomsky, 1988).

Only when all three conditions are simultaneously present does language use take on its special human character. As Chomsky summarized it:

“man has a species-specific capacity, a unique type of intellectual organization which cannot be attributed to peripheral organs or related to general intelligence and which manifests itself in what we may refer to as the ‘creative aspect’ of ordinary language use – its property being both unbounded in scope and stimulus-free. Thus Descartes maintains that language is available for the free expression of thought or for appropriate response in any new context and is undetermined by any fixed association of utterances to external stimuli or physiological states (identifiable in any noncircular fashion)”

(Noam Chomsky, Cartesian Linguistics, 1966).

It is a distinctively human trait to use language in a manner that is simultaneously stimulus-free, unbounded, yet appropriate and coherent to others. Such language use is neither determined (by a stimulus) nor random (inappropriate). This ability enables people to deploy their intellectual resources to any problem, or to create new problems altogether, putting our shared cognitive capacities to use across contexts at will. It is little wonder then why Descartes assigns such importance to language use in his test for other minds. A being that uses language in only one or two of the three ways described can be explained in mechanical terms – but the presence of all three is something that modern technology lacks the tools to create.

There’s no quick fix for this. First, it’s difficult to adequately specify what counts as ‘appropriateness’ – but we would not do away with it, for some uses of language are inappropriate and incoherent. Likewise, we may be tempted to assign to human language a controlling stimulus, not in the local environment, but in an internal state: perhaps the brain causes language use. Yet, the limits of explanation again disturb our inquiry here, just as they did the Cartesians’: physical causality, even in an internal (brain) state, is deficient as a ‘governing principle’ for language use, since it only explains the physical combination of linguistic elements, not the generation of meaning. Generally speaking, it does not account for the attribution of meaning to a remark. Nor can the term ‘stimulus’ be applied to any internal brain state without emptying the term of its present psychological meaning.

Still from I, Robot

I, Robot image © 20th Century Fox 2004

Back to the Machines

We return to the present, where the need to distinguish humans from machines made in our image remains strong. As Paolo Bory argues, technology firms who use the spectacle of human-machine showdowns, are in effect reintroducing Descartes’ problem to contemporary audiences (Deep New, 2019). While these firms’ aims are not intellectual, the resulting problem is similar, we’re confronted with a machine bearing, in either form or output, the image of humanity, and we’re being guided toward the idea that such machines have minds like ours. Existential doubt and an impetus to redefine humanity are only a few steps away. But do modern AI-enabled machines exhibit the creative aspects of language use? A reasonable (and honest) observation of LLMs reveals that they do not. They are:

Stimulus-Controlled: The output of a Large Language Model is predictably and inextricably tied to the input it receives. It transforms its input into an output by statistically manipulating a dataset. This means three things: (1) LLMs will generate an output having received an input, unless instructed to the contrary; (2) The operation performed over the input value is determined; it’s a product of the internal programming and external prompting; (3) The LLM will not alter the process of transforming an input into an output. So LLMs are fundamentally input-output devices, unlike the creative human mind.

Weakly Unbounded: Though LLMs are currently the subject of an ongoing debate concerning the implications for generative linguistics, the debate is often misframed. To be sure, LLMs can generate new text (converted from existing examples of language use) according to a specific configuration acquired during their training. This may be considered a ‘weak’ unboundedness. However, figures such as Descartes and Cordemoy were not concerned with the organization of strings of words into particular configurations; their concern was with the expression of thought; with the contents of one’s mind. In contemporary generative linguistics the productivity of language use that is being studied is the ability to generate an unbounded array of form/meaning pairs, not ‘the organization of strings’ (‘A Model for Learning Strings Is Not a Model of Language’, Murphy and Leivada, 2022). At least three reasons suggest LLMs do not achieve strong unboundedness. First, the persistence of distortions in their outputs and deficiencies or inconsistencies in their instruction-following indicate that they are not generating form/meaning pairs – showing that they have no concept of the meaning of the linguistic strings they create. Second, their training procedures are highly idealized compared to human language acquisition: they’re not in the world learning how to use language in response to experiences, as humans are. Third, state-of-the-art models like OpenAI’s, fail to represent principles of linguistic structure, but instead work through manipulating already existing texts (Murphy et al., ‘Fundamental Principles of Linguistic Structure are Not Represented by o3,’ 2025).

Functionally Appropriate Only: That LLMs are stimulus-controlled means that they lack humans’ ‘obscure’ condition of appropriateness in their language use. Being stimulus-controlled means they are not ‘inclined’ in certain ways, but rather, ‘impelled’ to do so. Therefore the question of choosing language for its appropriateness does not arise. The transformation of an input value into an output value based on internal programming and external instructions means that LLMs’ outputs are caused by stimuli, rather than being elicited by them.

For these reasons, we can see that LLMs do not meet the three criteria of Descartes’ test for minds. They fail to demonstrate the creative aspect of language use characteristic of humans.

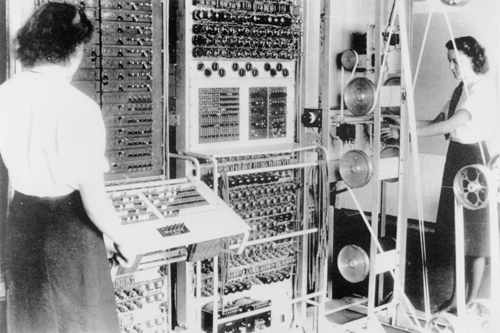

Colossus Mark 2 codebreaking computer being operated by Dorothy Du Boisson (left) and Elsie Booker (right), 1943

Human Outputs

What is the significance of this for human self-understanding? I have two immediate lines of thought, one directly related to LLMs, and another related more broadly to the study of human nature.

For one thing, this view reframes recent philosophical perspectives on the significance of LLMs. For example, Tobias Rees argued that ChatGPT-3 was just as epoch-breaking as Descartes’ Discourse on Method once was – with engineers having “experimentally established a concept of language at the center of which does not need to be the humans” (Non-Human Words, 2022). Moreover, Jonathan Birch, referencing Descartes, argues that LLMs “add great urgency to a question… what kinds of linguistic behaviour are genuine evidence of conscious experience, and why?” (The Edge of Sentience, 2024). These perspectives take Descartes’ remarks without linking them to the crucial theoretical accommodations of the twentieth century whereby the creative aspects of language use have been formalized. That LLMs do not replicate this way of using language is not particularly surprising – although a reassertion of human intellectual freedom is in order. LLMs are simply a different type of thing.

These ideas also raise a distinction between agency and intellectual freedom. Ball, noting biology’s traditional resistance to the notion of agency, contends that agency is nonetheless observable in commonplace creatures like fruit flies and cockroaches. There it consists of two components: (1) The ability to produce different responses to identical or equivalent stimuli; and (2) The ability to select among such responses in a goal-directed fashion. Yet neither condition entails a creative use of the organism’s cognitive abilities. And remember, human language use is neither deterministic nor random. A fruit fly that flies with random variation in its turning movements is not demonstrating free will. A cockroach that runs from the movement of air in a random path, is not free of the initial stimulus. Moreover, these goal-oriented behaviors have nothing analogous to appropriateness in language use. Finally, neither organism can be said to have a storehouse of thoughts relentlessly being generated throughout their lives; a storehouse that has its contents identified, retrieved, and reassembled for whatever situation or problem by the agent.

The philosophical problem runs deeper. Although some scholars argue that language is not necessary for thought, and is best conceived as a tool for communication, this neglects the original Cartesian problem (‘Language Is Primarily a Tool for Communication Rather than Thought’, Fedorenko et al, 2024). Just as the behaviourist B.F. Skinner stretched concepts like stimulus-control so far as to void them of scientific content, researchers today risk stretching concepts like communication to account for the otherwise ‘useless’ tool of language – a tool that, despite what they say, can be appropriately recruited for the deployment of cognitive and intellectual resources over an unbounded range at will (‘Language Is a ‘Quite Useless’ Tool’, Watumull, 2024).

Much more could be said, but it is clear that contemporary AI does not meet Descartes’ original language challenge, nor do conceptions of the human mind’s freedom advance with sufficient clarity on an ‘computational’ analogy.

Whether future AI systems could replicate true human linguistic behavior is an open question. There are reasons to doubt it. Human language use being neither determined nor random yet appropriate seems to put it beyond the scope of computation per se. The problem is not likely to be evaded by inserting ‘an added element of randomness or noise’ into a system to induce low-level indeterminacy, as Kevin Mitchell tentatively suggests (Free Agents, 2025).

Human beings are willfully creative creatures. “It is remarkable,” James McGilvray writes, “that everyone routinely uses language creatively, and gets satisfaction from doing so” (Cambridge Companion to Chomsky, 2005). The mind “can also be freed from current practical concerns to speculate and imagine.” In all this, humanity is an unusual species – one with an instinctive ability to use its cognitive abilities creatively, and which willingly wanders into what Larry Briskman (echoing Albert Einstein) describes as the darkness, attempting to ‘’shed light where none has been shed before…” (Creative Product and Creative Process in Science and Art, 1980).

This is the species that confronts AI. If we are thrown into self-doubt by existing AI systems that do not have minds, then it is incumbent on us to rescue the human mind from a misunderstanding entirely of our own making.

© Vincent J. Carchidi 2025

Vincent Carchidi is an independent researcher in cognitive science and the philosophy of mind, with an interest in artificial intelligence.