Your complimentary articles

You’ve read two of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Could a Robot be Conscious?

Brian King says only if some specific conditions are met.

Will robots always be just machines with nothing going on inside, or could they become conscious things with an inner life? If they developed some kind of inner world, it would seem to be like killing them if we scrapped them. Disposal of our machines would become a moral issue.

There are at least three connected major aspects of consciousness to be considered when we ask whether a robot could be conscious. First, could it be self-conscious (as in ‘self-aware’)? Second, could it have emotions and feelings? And third, could it think consciously – that is, have insight and understanding in its arguments and thoughts? The question is therefore not so much whether robots could simulate human behaviour, which we know they can do to increasing degrees, but whether they could actually experience things, as humans do. This of course leads to a big problem – how would we ever know?

In the Turing Test, a machine hidden from view is asked questions by a human, and if that person thinks the answers indicate he’s talking to another person, then the conclusion is that the machine thinks. But that is an ‘imitation game’, as seminal computer scientist Alan Turing (1912-1954) himself called it, and it does not show that a machine has self-awareness. Clearly there is a difference between programming something to give output like a human, and being conscious of what is being computed.

We ascribe conscious behaviour to other humans not because we have access to their consciousness (we don’t), but because other people are analogous to us. Not only do they act and speak like us, importantly, they are made of the same kind of stuff. And we have an idea of what we mean by consciousness by considering our own; we also think we have a rough idea what it’s like for some animals to be conscious; but ascribing consciousness to a robot that could act like a human would be difficult in the sense that we would have no clear idea what exactly it was that we were ascribing to it. In other words, ascribing it consciousness would be entirely guesswork based on anthropomorphism.

Much of what I’ll argue in the following is based (loosely) on the work of Antonio Damasio (b.1944).

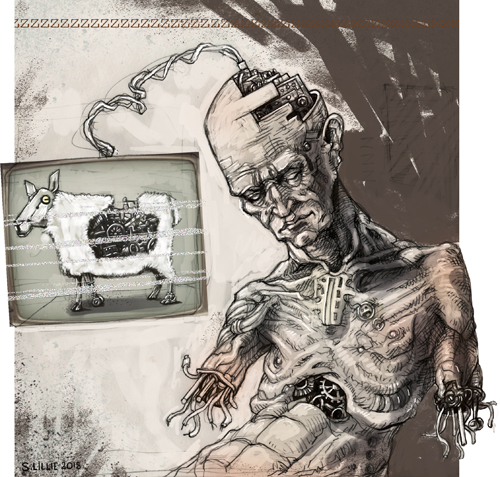

Robot I © Steve Lillie 2018 www.stevelillie.biz

The Stuff That Electric Dreams Are Made On

There are three ways a robot could be made, and these differences may have a bearing on whether it could be conscious:

(1) A possibly conscious robot could be made from artificial materials, either by copying human brain and body functions or by inventing new ones.

The argument that this activity could lead to conscious robots is functionalist: this view says that it doesn’t matter what the material is, it’s what the material does that counts. Consider a valve: a valve can be made of plastic or metal or any hard material, as long as it performs the proper function – say, controlling the flow of liquid through a tube by blocking and unblocking its pathway. Similarily, the functionalists say, biological, living material obviously can produce consciousness, but perhaps other materials could have the same result. They argue that a silicon-based machine could, in principle, have the same sort of mental life that a carbon-based human being has, provided its systems carried out the appropriate functional roles. If this is not the case, we are left saying that there is something almost magical about living matter that can produce both life and consciousness.

The idea that there’s something special about living matter was common in the nineteenth century: ‘vitalism’ was the belief that living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living objects because they contain some extra stuff. However, the discovery of the physical processes that are involved with living, reproduction, inheritance, and evolution has rendered vitalism redundant. The functionalist’s expectation is that the same will happen with ideas about the specialness of consciousness through the organic brain.

(2) Another way to make conscious robots could be to insert artificial parts and materials into a human nervous system to take the place of natural ones, so that finally everything is artificial.

Looking at medical developments, one can see how far this possibility has already advanced. For example, chips are being developed to take the place of the hippocampus, which controls short term memory and some spatial understanding (see Live Science Feb 23, 2011); or special cameras attached to optical nerves can allow blind people to see; nano technology can operate at a cellular and even a molecular level. However, the question is whether we could continually replace the human brain so that we are left with nothing that was there originally and still have a conscious being. Would replacing, say, bits of the brain’s neuronal circuitry until all the neurons have been replaced with artificial circuits mean that at some point ‘the lights go out’ and we’re left with a philosophical zombie, capable of doing everything a human can do, even behaving in a way indistinguishable from normal human behaviour, but with nothing going on inside?

(3) A robot could be made of artificial organic material. This possibility blurs the line between living and non-living material, but would possibly be the most likely option for the artificial production of a sentient, conscious being capable of feeling, since we know that organic material can produce consciousness. To produce such an artificial organism would probably necessitate creating artificial cells which would have some of the properties of organic cells, including the ability to multiply and assemble into coherent organs that could be assembled into bodies controlled by some kind of artificial organic brain.

Aping Evolution In Cyberspace

While it might be able to act and speak just like us, a robot would also need to be constituted in a way very similar to us for us to be reasonably certain that it’s conscious in a way similar to us. And what other way is there of being meaningfully conscious, except in a way similar to us? Any other way would be literally meaningless to us. Our understanding of consciousness must be based on our understanding of it. This not so much a tautology as a reinforcement of the idea that to fundamentally change the meaning of the word ‘consciousness’, based as it is on experiences absolutely intimate to us, to something we do not know, would therefore involve talking about something that we cannot necessarily recognise as consciousness.

The reason we would model our robot’s brain on a human one is because we know that consciousness works in or through a human brain. Now many neuroscientists, such as Damasio, think that the brain evolved to help safeguard the body’s existence vis-a-vis the outside world, and also to regulate the systems in the body (homeostasis), and that consciousness has become part of this process. For example, when you are conscious of feeling thirsty you know to act and get a drink. That is, while many regulatory systems are automatic and do not involve consciousness, many do. The distinction between doing something unconsciously and doing it consciously can be illustrated in the example of you driving home but having your conscious attention on something else – some problem occurring in your life – so that you suddenly find yourself parking in your driveway without having been (fully) aware that you were driving – not having your driving at the front of your mind, so to speak. Similarily, the question of robots being conscious can be rephrased as to whether they can ‘attend to’ something and be aware of doing so. Conscious, attentive involvement seems to have evolved when a complex physical response is required. So while you can duck to avoid a brick being hurled at you before you are conscious that it’s happening, you need to be conscious of thirst (that is, feel thirsty) in order to decide to go to a tap and get some water.

So one thing that’s special about organic/living stuff, is that it needs to maintain its well-being. But there is no extra stuff that makes physical stuff alive; instead there is an organisational requirement that necessitates the provision of mechanisms to maintain the living body. So to have a consciousness that we could recognise as such, the robot’s body would also have to be a system that needed to be maintained by some kind of regulatory brain. This would mean that, like our brains, a conscious brain in a robot would need to be so intimately connected with its body that it got feedback from both its body’s organs and also the environment, and it would need to be able to react appropriately so that its body’s functioning is maintained.

The importance of the body for consciousness is reflected in Damasio’s definition of it. In his book Self Comes To Mind (2010), he says that “a consciousness is a particular state of mind” which is felt and which reveals “patterns mapped in the idiom of every possible sense – visual, auditory, tactile, muscular, visceral.” In other words, consciousness is the result of a complex neural reaction to our body’s situation, both internal and external.

It could be further argued that emotions and feelings stem from two basic orientations a living thing can have – attraction towards something, and repulsion away from something. This is denoted in conscious creatures by pleasure and pain, or anticipation of these in the experience of excitement or fear. Feelings are the perception of the emotions. They are felt because we tend to notice and become emotionally involved with those situations which have a bearing on our well-being, and consciousness has developed to enable us to have an awareness of and a concern for our bodies, including an awareness of the environment and its possible impact them; and to deliberate best possible outcomes to preserve their well-being. So our emotions and feelings depend on us wanting to maintain the well-being of our bodies. To argue that a robot has a mind that would however be nothing like this because the robot’s body is not in a homeostatic relation with its brain, would therefore, once again be ascribing to that robot something that we could not recognise as consciousness. While a robot could mimic human behaviour and be programmed to do certain tasks, it would not be valid to ascribe feeling to it unless it had a body which required internal homeostatic control through its brain. So unless robots can be manufactured to become ‘living’ in the sense that they have bodies that produce emotions and feelings in brains that help regulate those bodies, we would not be entitled to say that robots are conscious in any way we would recognise.

Humans Understanding Human Understanding

These points also relate to the third question mentioned at the beginning – whether robots could actually understand things. Could there be a robot having an internal dialogue, weighing up consequences, seeing implications, and judging others’ reactions? And could we say it understood what it said?

Certainly, robots can be made to use words to look as though they understand what’s being communicated – this is already happening (Alexa, Siri…). But could there be something in the make-up of a robot which would allow us to say that it not only responds appropriately to our questions or instructions, but understands them as well? And what’s the difference between understanding what you say and acting and speaking as though you understood what you say?

Well, what does it mean to understand something? Is it something more than just computing? Isn’t it being aware of exactly what it is you are computing? And what does that mean?

One way of understanding understanding in general is to consider what’s going on when we understand something. The extra insight needed to go from not understanding something to understanding it – the achievement of understanding, so to speak – is like seeing something clearly, or perhaps comprehending it in terms of something simpler. So let’s say that when we understand how something works, we explain it in terms of other, simpler things, or things that are already understood that act as metaphors for what we want to explain. We’re internally visualising an already-understood model as a kind of metaphor for what is being considered. For instance, when Rutherford and Bohr created their model of the atom, they saw it as like a miniature Solar System. This model was useful in terms of making clear many features of the atom. So we can see understanding first in terms of metaphors which model key features of something. This requires there to be basic already-understood models in our thinking by which we understand more complex things.

As for arguments: we can understand these as connecting or linking ideas in terms of metaphors of physical space – one idea contains another, or follows on from other ideas, or supports another. This type of metaphor for thinking is embedded in our own physical nature, as linguistic philosopher George Lakoff and others have argued. Indeed, many metaphors and ideas have meanings which stem from our body’s needs and our bodily experiences.

There is also the kind of understanding where we understand the behaviour of others. We have a ‘theory of mind’ which means we can put ourselves in others’ shoes, so to speak. Here perhaps most clearly, our understanding of others is based on our own feelings and intentions, which are in turn based on the requirements of our bodies.

It is possible then that our conscious understanding boils down to a kind of biological awareness. In other words, our experiences of our embodied selves and our place in the world provides the templates for all our understanding.

So if there is a link between consciousness and the type of bodies which produce sensations, feelings, and understanding, then a robot must also have that kind of body for it to be conscious.

© Brian King 2018

Brian King is a retired Philosophy and History teacher. He has published an ebook, Arguing About Philosophy, and now runs adult Philosophy and History groups via the University of the Third Age.