Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

A Crisis of Attention

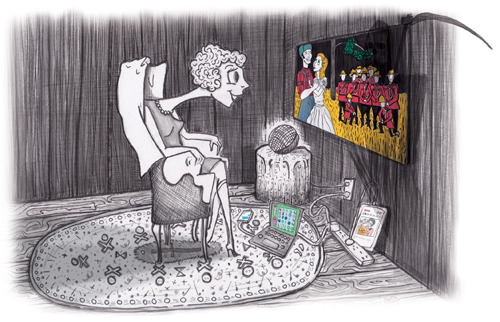

Paul Doolan attends to our culture of attention demanding.

‘Listen’ is composed of the same letters as ‘silent’. Listening to another person means falling silent while the other speaks, opening yourself up to what they have to communicate. The philosopher Byung-Chul Han describes this as ‘a special receptivity’ (The Disappearance of Rituals, 2020). Kieran Setiya argues that the path to strong relationships comes through cultivating the art of listening; forging new friendships often begins with the simple act of paying attention to the other person (Life is Hard, 2022). Too often, however, we fail to gift the other our attention or our time. I’ll admit that personally, this rings too true. I am a master of some widely practiced anti-listening habits: leaping into the pauses left by my interlocutor; finishing their sentence; rehearsing my own response while acting like I’m listening; replying in a way that shifts the focus of attention onto me… I’m guilty of them all. These days, it seems like we don’t have the time to pay attention.

The economist Herbert Simon characterised attention as a scarce resource: “In an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else; a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is … the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention” (Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World, pp.40-41, 1971). So when we pay attention, what we’re paying for is information. In this uneven exchange our attention is limited but the supply of information is limitless. So we need to be wise when we decide what we’re going to spend our limited currency on; after all, the quality of information varies enormously.

Since Simon penned his work, the battle for our attention has been transformed through the growth of online communication. Information circulates freely now, in a worldwide data-flow, and, vampire-like, sucks up our attention. Platforms vie with each other to provide us information in exchange for our attention. This has produced a crisis of attention.

Image © Susan Auletta 2025 Please visit instagram.com/sm_auletta

What is Attention?

‘Attention’ is derived from the Latin ad tendere, ‘to stretch toward’. Attention is directional – reaching to a physical object in the external world, or pointing inward towards a mental object (a feeling, idea, or concept). ‘Attention’ is also closely related to the French word attendre, ‘to attend’ or ‘to wait for’. So attention combines an active ‘stretch toward’ with a passive ‘wait for’ – as when we stretch toward a work of art or another creature, and we wait for it to disclose its secrets.

Attention works in two main ways. Involuntary attention is when your attention is captured by the unexpected or novel. You’re studying in a library and someone sits at your table, and you involuntarily notice their appearance or odour; or you’re listening to the sound of the waves on the beach when your smartphone pings and so you check another cute cat video on your feed. Your attention involuntarily travels in a new direction. Or attention may stretch toward a physical or mental object as a result of deliberation. You close your eyes in order to direct your attention to the music; or you put away your phone in order to give your attention to your dinner partner. Sometimes this act of voluntary attention can stretch for extended periods, forgetting all sense of time and even a sense of self. This deep attention enables a sense of rapture, described by Winifred Gallagher as “completely absorbed, engrossed, fascinated.” Rapt attention “simply makes you feel that life is worth living” (Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life, p.10, 2009). This is the result of effort. It needs practice. So in the current climate, where attention is simply the currency we pay to receive data, our capacity for rapture is in danger.

Distraction, Danger, Damage

We live in an age of distraction, which might also be called an age of madness – after all, we describe someone as ‘looking distracted’ when we mean they look mad; or when I need to justify a temporary bout of madness, I argue that I was ‘driven to distraction’.

James Williams, a former advertising strategist at Google, quit his job and went to Oxford to train as a philosopher. He argues that the struggle to win back control of our attention is ‘the defining moral and political struggle of our time’ (Stand out of the Light: Freedom and Resistance in the Attention Economy, p.xii, 2018). He was motivated to become a philosopher when he realized that he was suffering from a ‘new mode of deep distraction’ (p.7), and immersed in a ‘proliferation of pettiness’(p.57). He points out that Big Tech is involved in a major reorganization of our attention, and that we’re in danger of losing control over our attention processes by pursuing the diversions presented to us by Silicon Valley billionaires.

Yuval Noah Harari coined the term ‘dataism’ to describe the new secular religion that places freedom of information above all else. For the dataist, maximizing the dataflow and linking everything to the internet are the chief commands to be followed. We once sought meaning by looking inside ourselves; but the dataist connects to the dataflow in order to produce meaning, and a valuable life is no longer measured in meaningful experiences but by conspicuously sharing in the free-flow of data (Homo Deus, 2017).

To understand the dangers inherent in our distraction, we could do worse than turn to the aphorisms of seventeenth century French philosopher Blaise Pascal. In his work Pensées (Thoughts, 1670) we find a convincing articulation of the negative effects of what he called ‘diversions’. Pascal characterises humans as fragile creatures dignified by the possession of consciousness. Alas, humanity’s default condition is one of boredom and anxiety, and we endeavour to escape our boredom and depression by seeking distraction in diversions. Thus we are fooled by ‘the charms of novelty’ (aphorism 44), and end up paying too much attention to ‘things that do not really matter’ (aphorism 93).

Our chief motivation for this is fear of death. We seek distraction and excitement in order to avoid thinking about our inability to avoid death. Here Pascal asks us to imagine ourselves as one of a group of chained prisoners. Each day, some members of the group are picked out and butchered within sight of the others. One day it will be our turn. Such is the lot of humans. And yet, we flee from this truth by throwing ourselves into mindless diversions. Hence, the popularity of Instagram, Netflix, Snapchat, TikTok… We pursue distraction to seek consolation from our miseries, too; but distraction proves to be the deepest of miseries, because distraction, being a flight from reality and a denial of our mortality, ‘leads us imperceptibly to destruction’ (aphorism 414).

Pascal recommends placing one’s faith in a benevolent God, but we have largely replaced God with online entertainment. Netflix and other ‘opportunities’ leech away our attention so that we do not need to direct it toward uncomfortable truths. Moreover, in neo-liberal capitalism, with its focus on production, accumulation, and growth, death is banished because, in Han’s words, it ‘counts as absolute loss’ (The Agony of Eros, p.21, 2017).

Sherry Turkle’s Alone Together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other (2011) demonstrates the damage incurred through digital distraction, and warns that children suffer from a deficit of human attention, as increasingly they complete with screens for their parent’s attention, so suffering from the phenomenon of parents who are physically close but mentally far away. Teenagers, meanwhile, are aware of how little attention they receive from friends because they know how little they give; yet according to Turkle, what every young person longs for ‘is the pleasure of full attention, coveted and rare’ (p.266). But the smartphone has transformed us into conversational narcissists. The smartphone and earbuds are the killer of small talk. Turkle claims that teenagers flee from making an actual phone call “because it demands their full attention” (p.188). And Han argues that communication technologies promote a superficial, scattered form of attention that he calls ‘hyperattention’, and in this noisy world, “the ability to grant deep, contemplative attention” becomes “inaccessible to the hyperactive ego” (The Burnout Society, p.13, 2015).

Sacred Attention

Simone Weil

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) and Simone Weil (1909-43) are two very different philosophers, but one thing they share is the importance they give to the faculty of attention. For Nietzsche, voluntary attention can make us god-like in a Godless universe, while for Weil, contemplative attention gives us access to God. Weil argued that the only serious goal of education should be to train attention, for attention alone produces “beautiful art, truly original and brilliant scientific discovery… philosophy which really inspires to wisdom and… true, practical love of one’s neighbour” (An Anthology, p.273, 2000). In Twilight of the Idols (1889), Nietzsche argued that education should focus on learning to think, speak, and write; but ‘learn to see’ should take precedence. He explained that true seeing means “habituating the eye to repose, to patience, to letting things come to it; learning to defer judgement, to investigate and comprehend the individual case in all its aspects… not to react immediately to a stimulus”, adding, “all vulgarity is due to the incapacity to resist a stimulus… one has to react” (p.65). However, today, smartphones always within reach, we react immediately to a variety of involuntary stimuli, and measure our productivity by the speed with which we react.

Like Weil, Han argues that deep, contemplative attention produced “the cultural achievements of humanity” (The Burnout Society, p.13). And like Nietzsche’s deferred judgement, Hans stresses the need for engaging with the hard work of “freeing oneself from rushing, intrusive Something” (p.24). But the unending stream of information does not lend itself to providing a calm centre in our lives. Rather it turns us into ‘data fetishists’ (Non-things, p.2, 2022). Voluntary attention – that which produces art, philosophy, science, and care for others – is eroded and replaced by involuntary attention, which reacts in a distracted manner to the river of tweets, snapchats, BeReals, WhatsApps, and text messages.

Studying the art of the ancient Etruscans led D.H. Lawrence to argue that the act of ‘vivid attention’ was religious in its origin, an attempt of mankind “to draw more life into himself”, gaining vitality and “blazing like a god” (Etruscan Places, p.84, 1932). Thus Lawrence likened the purest form of attention to prayer or divination. Weil also argued that offering one’s full attention to another is a form of prayer, involving faith and love (Anthology, p.232). Really giving attention to the other involves transcendence of oneself. This distinguishes sacred attention from the sort of grasping attention that simply uses the other for one’s own benefit – the instrumentalised attention that’s simply a projection of oneself. The grasping form of attention is “bound up with desire”, but sacred attention “is so full that the ‘I’ disappears” (p.233). The proper application of attention produces ‘authentic and pure values – truth, beauty and goodness’ (p.234). For Weil, the worst outrage is the confinement of the worker’s attention to production processes, which ‘drains the soul of all save a preoccupation with speed’ (pp.275-276).

Iris Murdoch borrowed the word ‘attention’ from Weil to express “the idea of a just and loving gaze directed upon an individual reality” (Existentialists and Mystics, p.327), and said that what was needed in modern times was ‘a new vocabulary of attention’ (p.293). Like Weil, she equated attention with a type of prayer. And like Weil, she argued that attention should be directed outward, away from the self, and that this was done by developing the capacity for love. In words that reflect Nietzsche, Murdoch wrote, “It is the capacity to love, that is, to see, that the liberation of the soul from fantasy occurs” (p.354).

The Forest & Solitude

Some people favour the idea that technology can solve the problem that technology has wrought by providing the antidote to the distraction produced by the technology. This idea reinforces the myth of the technical fix – a belief in the magic of technology. Here we would do well to remember Plato’s warning that deception seems like a form of bewitchment (Republic, Book III, 413c, c.400 BCE). Communication technology enchants and seduces with its hyperreal simulation of the real and its unlimited promise to make our lives effortless. The sleek, smooth form of the smartphone or tablet bewitches us and draws us in, like Narcissus drawn to stare at the smooth surface of the dark pool, captivated by his own reflection.

The most popular digital detox app is ‘Forest’. By opening the app and setting down your device, you can grow a digital tree. If you give in to temptation and pick up your device too soon, the tree withers and dies. Yet rather than leading to you spending more time in the non-digital world, Forest gamifies and contaminates our lives with further digitalization. Much better to leave Forest at home and enter a non-monetized actual forest.

Romantic poets such as Coleridge and Wordsworth popularized the idea that walking in the forest or elsewhere in nature enhances our powers of deep attention. Nietzsche trekked over mountains and found his most productive refuge in the Swiss village of Sils Maria. Heidegger, who wrote that what is needed is “less philosophy, but more attentiveness”, retreated to his hut in the Black Forest to chop wood and to think. And according to Ludwig Wittgenstein’s biographer Ray Monk, it was in his hideaway in Norway that Wittgenstein had his most productive period: “the beauty of the countryside… produced in him a kind of euphoria” (Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius, p.94, 1991).

John Kaag argues that walking has been intrinsically “tied to creation and philosophical thought. Letting one’s thoughts wander, thinking on one’s feet, arriving at a conclusion” (Hiking with Nietzsche, p.27, 2020). Just so, the philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson tried to maintain a regime of walking in the woods every day. In a lecture in 1838, he recommended that a scholar must embrace solitude ‘as a bride’ in order to “become acquainted with his own thoughts”: temporary solitude is a necessity for the poet or philosopher who wishes to remain independent of the crowd. According to Emerson, one needs simplicity, silence, and seclusion to “pierce deep into the grandeur and secret of our being” (p.176). Likewise, Weil argued that the practice of deep attention is “impossible except in solitude” (Anthology, p.76).

Emerson’s student and friend Henry Thoreau built his own cabin on the secluded banks of Walden Pond, where he remained for nearly two years. In the solitude of the forest he developed a profound level of attention. He then reflected on his time and penned the classic Walden (1854).

Erling Kagge went quite a few steps further than Thoreau. He traversed Antarctica on foot, alone, claiming he could hear and feel the silence, and that nature “spoke to me in the guise of silence” (Silence in the Age of Noise, p.12, 2018). When he stopped for a break, “I experienced a deafening silence. When there is no wind, even the snow looks silent.” The result of this solitude: “I became more and more attentive to the world of which I was a part” (p.14).

Philip Koch says the type of solitude experienced by Thoreau and Kagge is characterised by three features: physical isolation, social disengagement, and reflectiveness. However, Koch argues that only one of these features – social disengagement – is necessary for solitude. He writes, “solitude is the state in which experience is disengaged from other people” (Solitude: A philosophical encounter, p.44, 2015). Even in close physical proximity to others and without the compulsion to engage in reflection, we can create moments of solitude, disengaged from other people, and enhancing our attention.

Aesthetic Attention

The best poetry is often the result of intensive attention. Poetry also often requires a manner of attending that sharpens and refines our capacity to listen, see, and feel. Poetry is not only a technique for tuning and refining attention, but also a way to interrogate the conditions and limits of attention.

Elisabeth Bishop’s poem The Fish opens with the line “I caught a tremendous fish”, and then describes him in detail. Her description of his eyes is the culmination of a great attention that shapes the reader’s perception:

I looked into his eyes

which were larger than mine

but shallower, and yellowed,

the irises backed and packed

with tarnished tinfoil

seen through the lenses

of old scratched isinglass.

They shifted a little, but not

to return my stare.

– It was more like the tipping

of an object to the light.

Fish blue Diego Delso 2020 Creative Commons 4

Bishop then writes, “I stared and stared”. The attentive, devotional gaze she offers is an example of Nietzsche’s admonition to learn to see: it leads inevitably to the last line, “And I let the fish go.” So the poem is a demonstration of a kind of sacred attention – a gifting and a prayer; and what’s received in return for deep attention is a lesson that goes far deeper than data: it teaches us that how we look alters what we see, and it teaches compassion for the other.

In a gallery, one is surrounded by the silence and stillness of art. It is the very stillness of paintings and sculpture that make them a challenge to look at when we’ve been conditioned by Netflix, YouTube, or our Instagram feed into a type of serialized looking – restless, superficial, and fleeting. A painting demands lingering. It takes time. In fact, according to Bence Nancy, all aesthetic experiences have one thing in common, namely “the way you’re exercising your attention” (Aesthetics: A very short introduction, p.22, 2019). Nancy argues that normally our attention is focused on a specific object, which leads to ‘intentional blindness’ – like when we’re so focussed on counting the number of basketball passes that we don’t even notice a person wearing the gorilla suit walking across the court (look up ‘selective attention test’ on YouTube if you don’t know what that’s about). But when we look carefully at an artwork we engage in ‘open-ended attention’ – not looking for anything in particular. This, according to Nancy, “liberates our perception” and we “let ourselves be surprised”. It directs our attention away from ourselves, and we discover what the art says to us – including that artists do not simply mimic reality, they select and highlight and thereby draw our attention to an otherwise unnoticed aspect of it. Eventually we turn away from the canvas, and see reality through new eyes. Alas, Nancy admits that the practice of open-ended attention “might be on its way out in our current smartphone obsessed times” (p.38).

The 2010 exhibition ‘The Artist is Present’, from performance artist Marina Abramowi ć , demonstrated the power of the human gaze and the profound experience of giving another person your prolonged, deep attention. Over the course of three months, Abramovi ć sat in silence at a table in New York’s Museum of Modern Art for eight hours a day, while members of the public lined up to take turns sitting opposite her. The audience member and the artist would then gaze at each other in silence. Some visitors sat with Abramowi ć for a minute, while others lost all sense of time and sat for well over an hour. Some were moved to laughter; many were moved to tears. I cannot think of another work of art that so emphatically emphasises the power of attention.

Conclusion

Setiya frames the loving attention of Weil and Murdoch as being an effort ‘to appreciate what’s there’ (Life is Hard, p.128). However, we no longer linger, because new information is constantly demanding our attention. Han argues that anything that is time-consuming ‘is on the way out’ (Non-things, p.6). Intense forms of attentiveness are being banished by destructive hyperactivity.

We give our attention away to a constant stream of trivial information. While the fish is still alive, we need to take the time to look into its eyes, recognize its creatureliness, attend to its suffering, then set it free. Then we need to spread the message of attending, before we descend into complete madness.

© Dr Paul M.M. Doolan 2025

Paul Doolan taught philosophy in international schools in Asia and in Europe, and is the author of Collective Memory and the Dutch East Indies: Unremembering Decolonization (Amsterdam University Press, 2021).