Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Prejudice & Perception

Xenos: Jacques Derrida on Hospitality

Peter Benson tackles xenophobia with the help of Jacques Derrida and Plato.

Jacques Derrida knew a thing or two about being an outsider. He was born of Jewish parents in 1930 in Algeria, at that time a French colony. Hence he was from birth a French citizen, although he did not set foot in France until he was nineteen. In 1942, by a decree of the wartime Vichy government, his citizenship was revoked because he was Jewish – without him being made a citizen of any other country. The major effect of this was his expulsion from the school he had previously been attending. So he was an Algerian who couldn’t speak Arabic; a Jew who was not a religious practitioner (nor could he read Hebrew); and an eventual immigrant to France as a pied-noir (the derogatory phrase used for the French from Algeria). These circumstances provided him with no solid sense of national identity. His subsequent academic career was pursued largely in unconventional institutions, and, in his later years, involved a great deal of travelling abroad. As a result, he was often the appreciative recipient of hospitality. American universities, in particular, frequently provided him with opportunities to teach and conduct research. He often spoke warmly of their welcoming environment. His books were read more widely in their English translations than they were in France.

Hard thought is always necessary to distinguish, from within a particular situation, factors of universal relevance. But the state of being an outsider, far from being a deterrent to philosophy, can be the very place from which philosophical questions are most readily raised. Furthermore, perhaps all of us today are immigrants of one kind or another. I have lived in Britain all my life and yet, with the substantial changes in society over that period, it is no longer the same country I was born into. I have thus, even by staying in one place, become a kind of immigrant – a bemused entrant into a new country just as surely as those who have physically moved from their own land. All of us need to make the best we can of such changing circumstances. The countries we have lost had numerous faults, along with their admirable qualities. Only those with very selective memories could deny this.

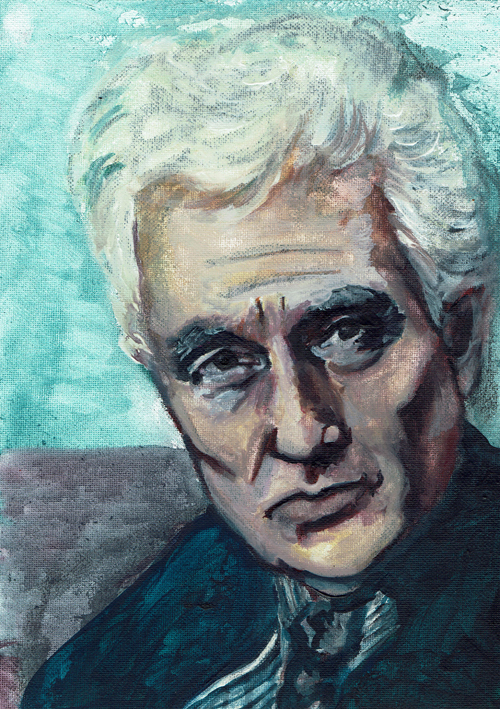

Jacques Derrida

© Gail Campbell 2017

The Philosophy of the Stranger

In his 1996 seminar Of Hospitality, Derrida discusses Plato’s dialogue The Sophist. This opens with Socrates being introduced to a visitor to Athens from Elea in southern Italy, the residence of several famous thinkers, such as Parmenides. Socrates expresses great pleasure in meeting this stranger. The Greek word for ‘stranger’ is xenos, also meaning ‘foreigner’. From this we get our word xenophobia. Socrates, by contrast, expresses a strong sense of xenophilia. He wishes to hear the stranger’s views, in the hope that they might open new perspectives on philosophical questions.

To facilitate this, Socrates steps back from his usual central role in Plato’s dialogues and hands his place over to the stranger, who then talks with Socrates’ friend Theaetetus. This stranger is never named in the dialogue; he remains simply a representative of foreign ideas. Having stepped back, Socrates does not speak again for the entire dialogue. In becoming silent Socrates reveals that the place from which he usually speaks is one appropriately occupied by a stranger. That is, when he is acting as the philosophical enquirer, Socrates himself speaks as a stranger in his own world, questioning those things that others take for granted.

Although not all strangers are philosophers, any viewpoint alien to our own can help us become aware of the perspectives we habitually and unthinkingly adopt. Obviously this doesn’t mean that we should immediately change our opinions to those of the stranger; but the more diverse perspectives we are able to comprehend, the less narrow and dogmatic our views will be. This interaction is a two stage process: first, an opening up to the other person in order to understand what they are saying; and only then considering the criticisms that might be made of this new viewpoint. A too rapid jump to this second stage is a common fault. This process is why Plato found dialogue to be the most appropriate form for philosophy, since dialogue cannot take place unless one first invites a stranger in, showing them hospitality rather than hostility. They may or may not bring us something of intellectual value, but without that initial hospitality we will never know. In the New Testament ‘Letter to the Hebrews’ (13.2) we are reminded: “Do not forget to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unaware.”

Derrida’s Hospitality

Raising these issues today, over ten years after Derrida’s death, we will all be aware of their relevance to events and circumstances filling our newspapers. In 1996, in his essay On Cosmopolitanism, Derrida wrote about the rights of asylum-seekers, refugees, and immigrants, paying attention to practical proposals as well as general principles. In particular, he discussed a proposal, current at that time, to establish cities of refuge that would be open to all, of any nationality or none. Here too he evoked a Biblical precedent (from Numbers 35:9-32) advocating cities to which anyone could flee from persecution.

Nothing came of this idea, and today the sheer magnitude of the flow of refugees from the chaos of the Middle East would make such an approach impractical. Politics, diplomacy, charity, and hard work will all be necessary, and philosophy has only a small contribution to make to this crisis. But that contribution can still provide guidance to the other efforts, and it is in this that Derrida’s discussions of hospitality are of particular value. What’s more, they exemplify a general feature of Derrida’s political thought whose significance has not always been recognized.

There’s a dilemma which Derrida asserts to be an inescapable feature of the concept of hospitality, which we see vividly revived in each successive refugee crisis, and in every discussion about immigration. On the one hand, there is a moral imperative to show hospitality, especially to people in distress or fleeing from danger; and on the other hand, the total abandonment of borders would obliterate the home into which they are being invited. All borders have some degree of permeability; but if it becomes absolutely open, then the border itself is abolished, and there is no longer any place of safety – any home – to enter.

Derrida sets this dilemma out clearly in Of Hospitality: “How can we distinguish between a guest and a parasite? In principle, the difference is straightforward, but for that you need a law; hospitality, reception, the welcome offered, have to be submitted to a basic and limiting jurisdiction” (p.59). ‘Hospitality’ assumes the ability to provide a safe haven, a shelter from storms, and like a biological membrane, the border must inevitably be selective when allowing itself to be crossed. If refugees fleeing from persecutors find their way through an opening, it cannot be equally open to those pursuing them. Every opening to others implies associated closings. As Derrida explains: “Between an unconditional law or an absolute desire for hospitality on the one hand and, on the other, a law, a politics, a conditional ethics, there is a distinction, radical heterogeneity, but also indissociability. One calls forth, involves, or prescribes the other” (p.147). The particular balance between these two indissociable aspects of the notion of hospitality, openness and closedness, will depend of course on particularities of circumstance. There is no simple calculus we can apply to resolve each dilemma, no one definitive way to respond appropriately in each particular case. However, both sides of the dilemma must always be kept in mind. The idealistic claims of an unrestrained hospitality, though impossible to follow as a law, must never be completely silenced by claims of impracticality.

Derrida on Political Dilemmas

In his later writings Derrida repeatedly uncovers similar dilemmas inherent in the central terms of our contemporary political thinking, such as Justice, Democracy, and Human Rights. He does this not to dismiss these concepts, but to show the doubled attention that each requires of us. Failures in these fields occur when one side of the dilemma temporarily obliterates our awareness of the other. Another common contemporary example is in the dilemma between freedom and public safety. Unfortunately, Derrida’s mode of analysing these concepts, through the process of ‘deconstruction’, does not provide immediate answers to urgent questions. Nevertheless, it yields a more clear-sighted awareness of how responsive action must begin, and shows that we cannot evade our responsibility by the use of general formulaic solutions.

Take the case of Democracy, for example: the value of this notion begins to deteriorate as soon as people imagine that they have achieved a fully-functioning democracy in the institutions they have established. For it is under the cloak of this complacency that factions begin to utilize those same democratic institutions as the means for attaining and maintaining their own power. There is no fixed solution which will permanently eradicate this problem. Rather, our laws and institutions need to be continually modified towards greater and greater democratic inclusiveness and transparency, without imagining that this process can ever reach perfection. We can only commit ourselves to a ‘democracy to come’, to use Derrida’s phrase, rather than to any current inadequate approximation of democracy.

And so it is with hospitality too. We should never plump ourselves up with the bland conviction that we are a hospitable people. Rather, we must be constantly alert as to how we can become more hospitable, whilst avoiding a catastrophic collapse of the region of safety we envisage in the word ‘home’. So Derrida’s is not a philosophy that offers definitive answers to these dilemmas, since such an answer would necessarily be wrong, if we are dealing with a true dilemma. Rather, it alerts us to the fact that we are always in the situation of never having done enough. The hospitable person or country should be seeking at all times to be more hospitable, alert to any opportunities to move in this direction, never saying, “we’ve done enough, we can’t do more,” rather, always seeking practical ways to do more than we have.

© Peter Benson 2017

Peter Benson is no stranger to philosophy, having studied it at Cambridge University.