Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Visions of Society

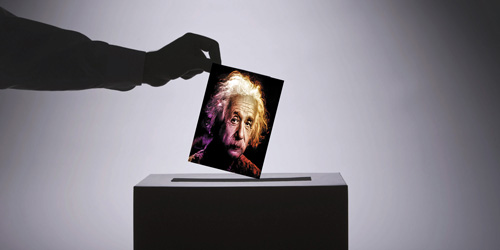

Informed Voting

Lorenzo Capitani is in favour of government through knowledge not ignorance.

I would like to suggest an improvement of an important aspect of the current democratic model – the voting practices which give access to legislative power – based on the idea that only people who have an interest in a specific issue and have knowledge pertaining to that issue should be in a position to influence a decision regarding it. In this way, as the problem is analysed and the responsibility is shared among informed minds, then if not the best, at least an adequately good decision, is made.

In representative governments this principle of informed decision-making is often satisfied by policies being examined by a restricted and specialised commission which generally considers the concern, takes a vote, and passes their conclusions over to their political general assembly, which examines the matter and takes a final decision. However, here the amount of people involved on a specific issue is really small! Only in countries where issues are constantly reviewed by referenda and the voting model approaches most the concept of democracy, such as Switzerland, are laws examined and backed or rejected with a considerable degree of consensus. The population itself is directly involved in the decision-making. As there is no obligation to go to vote, this means that anyone who votes will actually be concerned about the issue, and it might fairly be hoped that the citizen has researched the matter they will be voting on.

However, even this democratic model is incomplete, as it allows individuals who have done less research in a specific area to have a vote that counts just as much as those who have done more research. A better, albeit more complex system, would weigh someone’s vote on an issue according to the education they have attained in that field. So for example, the vote of a miner would count more on matters of mine safety than the vote of a shopkeeper; the vote of a doctor would be more important on health matters than the vote of a policeman; and so on. The extent of peoples’ areas of knowledge could be measured by public exams. In order for an individual’s vote to count in a specific theme, it would be sufficient that that individual obtained the certification necessary. Fairness would be guaranteed, as people could specialise however they wished in the various fields of knowledge.

Majority rule would still prevail. However, if social cohesion within a free community is to be maintained, the rights of the minorities must also be given ample space. The biggest risk of democracy is the abuse of power by the majority over the minority. The only tools available to fight this are tolerance, empathy and understanding. Once again, education is key.

This system would allow citizens to contribute to their community according to their interests, and would remove the discrimination that exists between majors and minors, since age would no longer be a discriminating factor, it would be replaced by knowledge and ability. The system could also encourage lifelong education: privileges to individuals such as tax breaks could be allocated according to the degree of preparation and exams passed, thus giving an incentive for the individual to make a greater contribution to the community. The system should also allow for the downgrading of an individual as knowledge that isn’t cared for is unfortunately forgotten and the ability to contribute positively in that field is lessened.

This would thus be a dynamic system and not static. It would also be much more complex and difficult to manage than current systems. The ability to vote based on merit and the responsibility of direct rule, are all traits of a system that can be applied only in a very advanced community, capable of managing its differences without conflict and without the need to impose its decisions. However, the infrastructure and the technology for such a system already exist. Voting can very well take place on the internet, allowing referenda to be used as a legislative tool at a very low cost. The internet can also be used to convey arguments for and against different issues, once again at a very low cost, without the need to spend millions on advertising slogans that fail to convey the complexity of an issue. Schools could also be employed in the evenings for the exams.

Why is democracy not dictatorship the better form of government? Even dictatorships can allow for substantial economic success, so economics seems not to be the deciding factor. So what is? The answer is simple: Ideas. Democracy allows for debate and freedom of thought; and although culture is a homogenising factor, individuals are allowed to examine situations from different standpoints. More ideas are thus generated, and the community has a greater potential for development in many areas, including but not limited to economic development. The problem is that if a community is not ready for democracy all sort of behaviours will crop up that destabilise the system. Thus we find corrupt or abusive democracies, where politicians worry more about their personal interests rather than the wellbeing of all. In the model I have proposed specialised politicians no longer play a definitive role; rather, each individual becomes a politician. There is no longer a person to imitate, but rather a political behaviour and style of life that should be common amongst all members of the community, and which is taken for granted. Political heroes are no longer necessary, for each individual would be a hero and campaigner in those matters he or she deems worthy.

© Lorenzo Capitani 2016

Lorenzo Andrea Capitani has a degree in Business Economics from Bocconi University in Milan.