Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Films

Hit Man

Jason Friend and Lauren Friend discuss reprogramming your self.

Gary Johnson, the protagonist of Richard Linklater’s film Hit Man (2023), is a philosophy professor. In the middle of the film he poses the following question to his students: “What if your ‘self’ is a construction? An illusion, an act, a role you’ve been playing every day since you can remember?” This is the central question the film tries to explore, for Johnson is not only a philosophy professor but also an undercover agent for the New Orleans police who pretends to be a wide variety of hitmen in order to ensnare those who would purchase his murderous services.

Along the way, Gary falls for one of his would-be clients, Madison, a woman so desperate to escape her abusive marriage that she wants to hire a hitman to kill her husband. This creates an odd situation, because Gary, who is actually a soft-spoken, introverted intellectual, meets Madison when he is in character playing Ron, a charismatic alpha male who happens to kill people for a living. Gary decides to embark on his romantic relationship with Madison in the guise of Ron. Thus, when Gary asks his identity query to his students, it is no simple hypothetical; and as the film progresses it becomes less clear if Gary is merely acting like Ron, or is actually becoming the new self he invented.

Gary himself initially seems skeptical that he can change his core self. In a conversation with his ex-wife Alicia, he posits that it is only possible for individuals to change “within our set-points, which really isn’t that much.” Alicia, a psychologist by trade, pushes back, asserting that “researchers are finding that people can change their personalities well into their adulthood… The five traits that make up personality – extroversion, openness to experience, emotional stability, agreeableness, and conscientiousness – can all be altered within just a few months.”

This is the intellectual standoff at the heart of the film – is it possible for an individual to radically change his own identity?

While the film plays with this question throughout, its ultimate answer is a resounding yes. By the end of the film, Gary has committed acts he once would have considered unthinkable, and he synthesizes the seemingly polar personalities of Gary and Ron into one new being, transforming into a much more successful philosophy professor who captivates his growing classes with his newfound confidence and charisma.

On the day of the final exam, he tells a rapt crowd of students that he “used to believe that reality was objective, immutable. And we’re all just sort of stuck, in a Plato-Descartes-Kant sort of way… But over the years, I’ve come to believe… there are no absolutes, whether moral or epistemological. Now, I find this to be a much more empowering way to go through life – this notion that if the universe is not fixed, then neither are you, and you really can become a different, and hopefully, better, person.”

Gary here credits his new perspective on identity to his shifting from an objective to a relative view of reality and truth. This is perhaps not surprising in a film that starts off with a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche. And yet, Gary’s newfound philosophy seems more indebted to Jean-Paul Sartre than Nietzsche, for although the film begins with Nietzsche’s exhortations to ‘Live dangerously!’ and ‘Live at war with yourselves!’, Nietzsche himself intended such messages only for the select few – an elite band of Übermenschen who rise above the masses. Sartre, on the other hand, promoted a much more optimistic and inclusive vision – of a world in which all individuals have the capacity to reshape themselves.

This view is encapsulated nicely in Linklater’s earlier and most directly philosophical film, Waking Life (2001). The protagonist of that film talks to Robert Solomon, a notable Sartre scholar. While existentialists are often caricatured as perpetual pessimists, Solomon flips the script and praises them as optimists, asserting that “one thing that comes out from reading these guys is not a sense of anguish about life so much as a real kind of exuberance of feeling on top of it. It’s like your life is yours to create.” He concludes his summation by insisting that the biggest takeaway from Sartre is that “It’s always our decision who we are.” Hit Man transports such Sartrean sentiments straight into Gary’s closing speech as he endorses the view that it is possible to radically change yourself, and emphasizes how liberating it is to refashion yourself into whoever you want to become.

Gary as a nice guy philosophy teacher

Film images © Netflix 2024

Off-Target: The Reality of Reprogramming

But to what extent is the film’s view of the malleability of the self correct? Can key personality markers really be changed in a few months? Is it possible for someone to just fake it until he makes it and becomes a completely different person?

In previous reviews in this magazine (on WandaVision in Issue 152 and Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness in Issue 159), we developed the concept of the ‘identity algorithm’, a model that sees the self as a product of ‘code’ partially written by nature and partially by nurture, which dictates an individual’s reactions. One’s code is the cause of every thought, feeling, or action, and it creates patterns of predictable behaviors that we know as an individual’s personality.

This model emphasizes that identity is deeply embedded: a quite ordinary decision can be the result of thousands of factors – thousands of ‘lines of code’ written into a person’s psyche over the course of his or her lifetime. Yet much of one’s identity algorithm remains unknown to the individual, as substantial portions of it are encoded in hard-to-decipher aspects of the self, such as genes (each individual has between 20,000-30,000) or the unconscious. Therefore this identity algorithm model, which emphasizes the deep-rootedness and opacity of identity, seems very much in tension with the idea that the self is but a role that one can entirely alter within a few months.

The closest approximation to Gary’s approach to changing himself is perhaps method acting, in which an actor tries to fully immerse themself in the psyche of their character. There’s a long history of overblown claims for method acting, usually cast as fears that actors might become unhinged by a particularly intense role. For instance, in the wake of Heath Ledger’s death, there was much sensationalist media that attributed it to a psychological imbalance prompted by Ledger’s submersion into the role of the Joker in The Dark Knight (2008).

The article ‘Acting changes the brain; it’s how actors get lost in a role’ (Aeon, 2019), by Christian Jarrett, a cognitive neuroscientist, exemplifies the curious trend of authors making sweeping claims about the impact of acting on personal identity from scanty evidence. For instance, Jarrett refers to a neuroimaging study on actors while acting which revealed a “deactivation in regions in the front and midline of the brain that are involved in thinking about the self”, and then quotes the researchers who ran the study speculating that “this might suggest that acting, as a neurocognitive phenomenon, is a suppression of self processing.” This is a fascinating idea, but like all the studies Jarrett cites, it only examines the immediate impact of acting on an actor’s brain. None of the studies he refers to even attempt to demonstrate long-term changes to an individual’s core personality as a result of acting. Yet, from these short-term studies, Jarrett jumps to proclaiming that, “In light of these findings, it is little wonder that actors, who sometimes spend weeks, months or even years fully immersed in the role of another person, might experience a drastic alteration to their sense of self.” Here we see a sort of funhouse mirror effect, in which a study uncovers a tangible but limited impact, the researchers themselves offer their own interpretation as to what it could mean, and then a third party exaggeratedly interprets that interpretation as support for a much more significant claim. However, since the neuroimaging studies do not actually prove any long-term cognitive changes produced by acting, it seems rash to assert from these studies that a shy philosopher like Gary could really transform himself into a real bad boy like Ron just by inhabiting the role.

But while research might not actually support the idea that acting can radically alter the self, what about Alicia’s broader claim that all of one’s personality traits can be transformed within a matter of months?

This assertion seems to be based on the website Big Think’s piece, ‘If you don’t like your personality, you can change it’ (2021), by Dr Elizabeth Gilbert, a psychologist. Gilbert initially states that “Until recently, I would have told you to resign yourself to a life with your fate-given personality”, but then proclaims that “over the last few years, researchers have begun finding evidence that personality is not completely out of our control. Instead, people may be able to intentionally change their personality traits.” Gilbert bases her newfound optimism on work by Marie Hennecke. However, when one actually digs into Hennecke’s work, the picture becomes more complicated.

Hennecke, a professor of psychology, proposes a three step framework under which it might be possible for an individual to intentionally reprogram one of their core traits, for instance, transforming oneself from an introvert into an extrovert. This is a provocative idea, since many scholars (such as Stephen Pinker in The Blank Slate, 2002) have long maintained that the ‘big five’ personality traits are genetically hardwired and relatively immutable. Yet Hennecke’s 2014 meta-analysis of psychological studies, ‘A Three-Part Framework for Self-Regulated Personality Development across Adulthood’, does provide evidence that it’s possible for an individual to intentionally change one of the core facets of his or her personality – but only if a wide variety of conditions coincide. This is why one of the last sections of Hennecke’s paper is entitled ‘The limits of self-regulated personality development: Why don’t people change more?’. Hennecke begins this section by conceding that “people’s personalities, in fact, change relatively little across adulthood.” She then spells out the wide array of factors that can inhibit identity change, making it quite a rare occurrence in adults. So although Gary transforms his identity with relative ease, a closer look at the research suggests that reprogramming one’s self is not so simple. This is not meant to suggest that identity change is impossible, only that it is difficult.

One of the more effective methods of behavioral change is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). In CBT, people, usually under the guidance of a therapist, identify thoughts that lead to undesirable behaviors, interrogate those thoughts, and gradually reshape their thinking over time. The process is slow and incremental, and while small changes in thinking can lead within a few months to tremendous relief from anxiety and other forms of destructive thinking, there is no evidence that CBT can lead to wholesale personality changes of the kind we see with Gary. Other methods of psychological transformation, such as mindfulness in Buddhism, also indicate that while change is possible, it takes considerable time and effort to reshape one’s psychological processes. Anyone who has seriously tried to meditate quickly realizes that our thought processes are hard to control. As the Buddha’s metaphor so aptly describes, our minds are unruly monkeys jumping from thought to thought. To actively change one’s personality, one would need to spend considerable time and energy to effectively train the self.

Compared to the painstaking process of meditation or the cognitive behavioral approach of tracking down and reshaping individual thoughts, Gary’s method of just trying on a new personality and faking it until he (re)makes it seems much easier, and a lot more fun. However, the reality of identity change aligns much better with the identity algorithm model than the film’s easy-breezy portrayal of the self as a role that one can just choose to stop playing. Rather, our programmed identity is deep and partially unknown to ourselves, so changing ourselves is a slow and arduous process of trial and error, rather than the quick fix in the film.

Gary and Madison

It Takes A Village To Raise A Hit Man

Hit Man is an entertaining film, so its depiction of Gary’s transformation can seem like a bit of harmless fun, perhaps even a source of inspiration. Linklater certainly seems to think so, because right after Gary tells his students about his embrace of existentialist individualism (you make your own meaning and self), he delivers a rousing pep talk in which he muses that “As we close out this semester, if I have one piece of advice for you moving forward in this complicated world, it’s this: seize the identity you want for yourself. And whoever you wanna be after this class, be them with passion and abandon.” After all, if an ordinary guy like Gary can become a completely new man in just a few months, anyone else can, too.

The danger of this feel-good philosophy, is that it essentially props up a version of the myth of the rugged individual. The film’s logic implies that if an individual isn’t successful in transforming themselves into the glamorous and passionate individual they’ve always fantasized about being, they just haven’t pulled on their bootstraps hard enough.

The philosopher Gregg Caruso has pointed out that those who most believe in free will also have the highest rate of ‘just world’ belief – the idea that people deserve the lives they live. This directly connects to the philosophy of identity, because if, as Hit Man suggests, people can change themselves into whomever they want to become, then we as a society need not redress social inequality, because if they just put their minds to it everyone can create the idyllic lives they desire. This is pretty much as Gary and Madison end the film – by integrating their newly-forged badass selves into the stereotypically sweet suburban dream. A misguided belief in protean Sartrean individualism lets society completely off the hook by putting the burden entirely on the individual to change themself.

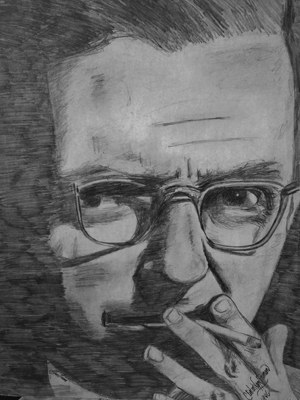

Sartre looking sceptical by Clint Inman

However, if we instead recognize the tremendous difficulty involved in refashioning one’s identity, we may start to consider social barriers that prevent people from engaging in beneficial self-reprogramming. For example, childhood poverty has recently been linked with the development of weaknesses in the white matter of the brain as well as significantly lower levels of gray matter development. These deficits can limit one’s ability to problem solve, process information, and regulate emotions. If we expect people to be able to change themselves, we need to ensure that they have the optimum mental capacity. Allowing childhood poverty to persist – and perhaps even worse, ending programs that have been proven effective to relieve childhood poverty – decreases the likelihood of a child having the mental resources needed to engage in the hard task of reprogramming their identity. Indeed, Professor Hennecke, who wrote the personality change framework to which the film seems indebted, also warned in her paper “that the degree that individuals do not have the necessary self-regulatory resources such as energy, attention, time or skills that need to be invested into behavioural change, [means] they may not be able to change. For example, a fully employed parent of two children who is also taking care of their aged parents may be too tied up in daily responsibilities even to consider self-improvement.” So while the film uses Gary to represent the everyday man’s capacity for change, it seems important to note that Gary lives a uniquely privileged life in which he has no money problems and no obligations to anyone but himself. Even though reprogramming one’s identity would be hard even for someone in Gary’s situation, using him as the baseline example ignores all the other factors that can impede the reshaping of one’s self.

In order for the majority of people to have both the ability and the opportunity to refashion themselves, the world would need to change. So although Hit Man and Waking Life both promote Sartre’s individualist existentialism, they ignore the other side of the coin, his political existentialism, in which he continually reminded us that we must also take responsibility for our social order, and urged us to work to reshape it for the better. Indeed, perhaps one of the reasons Sartre found Marxism so appealing was its insistence on restructuring society so as to liberate individuals from the economic constraints that prevent so many from exploring their potential. And while there are many serious problems with the Marxist vision Sartre prompted, there are valuable lessons to take from it as well. Our societies need to prioritize policies that truly nurture children to developing the cognitive capacities necessary for self-reflection and growth, such as food security, quality education, and safe housing. Society also needs to create social structures that give adults the space and support they need in order to have the time and energy to engage in reprogramming their own identity algorithms if desired – such as affordable daycare, quality healthcare, and a shorter work week. It must also provide educational opportunities for both students and adults to learn about and implement self-changing strategies that actually work.

While Gary exhorts his students to “seize the identity you want for yourself” right before he distributes his final exam, passing the identity test will take far more than one steely individual putting in two hours of concentrated effort all by their lonesome. It’s a test that we must all work together to pass.

© Jason Friend and Lauren Friend 2025

Jason Friend has an MA in English from Stanford University. He teaches literature and philosophy in California. Lauren Friend has an MA in Educational Administration from Concordia University. She is the Dean of Faculty at Pacific Collegiate School.