Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Macmurray on Relationship

Jeanne Warren presents aspects of John Macmurray’s philosophy of the personal.

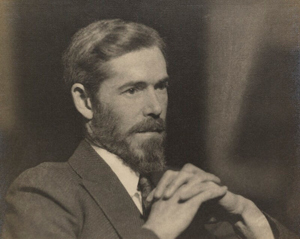

It was good to see an article on John Macmurray (1891-1976) in Issue 167 of Philosophy Now. The author, Colin Stott, ended by suggesting that Macmurray is “worthy to stand alongside Russell and Wittgenstein as a leading philosopher of the twentieth century.” I heartily agree. So here I would like to examine briefly some of Macmurray’s analysis of the interpersonal, by presenting some features of his philosophy of ‘persons in relation’.

In his writings Macmurray devotes as much space to spelling out an alternative to the egocentric bias of Western philosophy as he does to arguing against its theoretical bias. Regarding the theoretical bias, he concludes that ‘I do’ is more foundational than ‘I think’. Regarding the egocentric bias, he argues that the fundamental unit of personal reality is not ‘I’, but ‘you-and-I’. We can note a connection by observing that ‘I do’ implies a ‘you’ interacting with an ‘I’, but Macmurray’s two criticisms remain distinct. Macmurray didn’t argue for the importance of positive personal relationships, he started from it, observing that the most valued thing in our lives is the relationships central to them, giving our lives meaning. Sartre said “ Hell is other people” : Macmurray could equally have said “ Heaven is other people.” Both are true, but Macmurray is more inclined to dwell on the positive.

An account of personal experience needs to include feeling as well as thinking. The first Macmurray book I read was Reason and Emotion (1935). In it he presents much of his basic position, including the contention that feeling as well as thinking can be rational or irrational. He also argues that our relations with one another lie on a spectrum running from fear to love. Relations based on love he broadly terms ‘friendship’. In this context the term ‘love’ does not mean a passionate attachment, but rather a positive, open relationship. Fear is its opposite, negative and closed.

The foundation of positive relationships is, with luck, laid in early positive experiences within the family. Macmurray starts with the relationship of the infant with its primary care-giver – most often the mother. This, rather than an isolated existence, is how we all begin. The evidence from psychology is piling up that a positive early relationship with a primary care-giver is a life-changer for the growing infant. If love is absent, the damage is equally stark. At the same time, the difficulties of ever-larger numbers of people living together peacefully are forcing themselves on our attention. Both these aspects of our interpersonal lives are dealt with by Macmurray as he seeks to provide a philosophy adequate to the whole of our experience.

Concerning our experience with groups, Macmurray makes an important distinction between associations which are ends in themselves – that is, for their own sake – and those which are for the sake of some other end. Both are necessary, but they’re not to be confused. Macmurray sometimes uses the word ‘community’ for the former. A loving family is an example of a community. Here each individual feels valued and would be missed if lost – not because of their practical contribution to the unit, but simply because of who they are. But necessary to the support of personal communities are associations between people to achieve specific purposes. They are in some sense impersonal, but they are essential. These functional relations are what Macmurray calls ‘society’: they include our work lives, systems of politics, economics, and justice, among others. One of Macmurray’s formulas is, ‘The functional is for the personal; the personal is through the functional’.

Macmurray’s preference is to use ordinary English words for concepts that he defines quite precisely. However, the danger here is that the reader will be misled or confused. For example, by selecting the term ‘friendship’ to stand for any positive relationship, Macmurray does not make it obvious that it includes the relationship between a child and its parent. He also fails to provide a parallel term for negative relationships, even though he analyses the roots and effects of fear in some detail. Similarly, the difference between what he means by the terms ‘community’ and ‘society’ is fundamental to his thinking about politics, education, and religion, enabling him to make distinctions impossible to make by those who only distinguish between an individual and a group. Yet because ‘community’ and ‘society’ are common words we often use interchangeably, we may tend to ignore the distinctions he so carefully makes, and impose our prior understanding when reading his arguments.

Macmurray’s thought developed before an awareness of depth psychology had spread. I happened to discover Jung in the same year I discovered Macmurray. The concept of the unconscious, as explored by both Freud and Jung, helps to flesh out the concept of ‘person’ Macmurray presents, as Macmurray wrote for the most part about our conscious selves (although he did come to value Jung’s work later). Yet Macmurray’s view of persons was wider than that of most philosophers because of his inclusion of feeling, action, and relationship as fields for rigorous philosophical consideration. Macmurray proceeds always on the basis of honesty and freedom of thought and feeling. This is his case against egocentricity: that we cannot find out the truth about ourselves if we’re entirely self-interested. This requirement gives his writing a moral tinge, but he is not a moralist laying down rules of behaviour. He certainly hoped for a better world; but then, that could be said of many philosophers. He certainly never sacrificed the search for truth to a desire for any particular outcome. Indeed, his ability to value feeling without sacrificing truthfulness – his insight that feeling itself could be appropriate (rational) or inappropriate (irrational) – underlies his unique contribution to modern philosophy.

© Jeanne Warren 2025

Jeanne Warren is a founder-member of the John Macmurray Fellowship, which aims to make Macmurray’s work better known. She is also a member of the Oxford Philosophical Society.