Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Interview

Peter Singer

The controversial Australian philosopher defends the right to choose to die on utilitarian grounds. Matt Qvortrup recently asked him about it.

The Northern Territory in Australia was the first place in the world to legalise euthanasia. It was in 1996. After a year, the federal government stepped in and banned the procedure. Now, thirty years on, all jurisdictions in Oz allow people to voluntarily die. Recently I made a short documentary about it, including interviews with the widow of the first person to die, and with the doctor who oversaw his death – his name was Nitschke. His surname led us to talk about Nietzsche, and then philosophical ethics, and Peter Singer’s name came up. “You should speak to him”, said the doctor. Before I could say anything, he said: “This is his number and email. I’ll put in a word for you.” And so he did, and so I could interview the world’s most controversial philosopher.

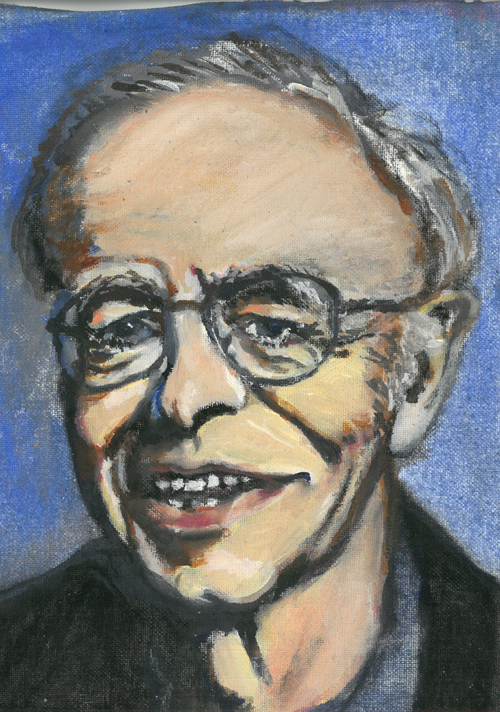

Peter Singer by Gail Campbell

“I have no idea what Aristotle would say.” Peter Singer is perhaps the world’s leading moral philosopher, but he is not pretending to be omniscient. He is world famous for putting Animal Liberation on the agenda with his book of that title in 1975.

He might have done much to atone for the sins of René Descartes – who regarded animals as insentient beings. But he has caught much controversy especially with his views on voluntarily assisted dying – or VAD, as voluntary euthanasia is called in Australia.

His muscular defence of the “right to die” is nothing new. Over the years it has had consequences for Singer, and also for the institutions he worked for. It resulted in Princeton University losing money from benefactors who took exception to the Ivy League university appointing Singer to the Ira W. DeCamp Chair of Bioethics in 1999. But he still stands by his views.

Singer was born to Jewish parents in 1946. They were Austrians who emigrated to Australia when Hitler invaded their country in 1938. The household observed Jewish holidays but was agnostic. Young Peter Singer took a stand. He was an atheist and refused to have a Bar Mitzvah – the religious coming-of-age ceremony. He studied philosophy at the University of Melbourne, and later had a stint at Oxford University where he specialised in political philosophy. It was in this phase that he wrote two short books on the philosophies of Karl Marx and G.W.F. Hegel.

Singer has never abandoned political philosophy – and he even wrote a cheeky book on it titled The President of Good and Evil: The Ethics of George W. Bush. Written at the height of the Iraq War in 2004, in it he used ethical and political theory to reconstruct the philosophy of the then US president.

But it was his book Practical Ethics that gave him the status of a major philosopher. Covering themes ranging from abortion, through to political violence and overseas aid, the book did exactly what it said on the tin: it was a book on the practical use of philosophy. That Singer became notorious was due to his views on euthanasia.

At a moment when this particular issue is being debated in the United Kingdom Parliament, his thoughts are perhaps particularly timely now – and certainly controversial. Some would even say distasteful, “Parents should have the possibility if they so choose to humanely end the life of a severely disabled infant after obtaining advice, not only from the doctors but also from those with personal knowledge of what it is like to have a child with that disability”, he told Times Radio in an interview last year.

Some might see his defence as concerning a purely hypothetical situation. But an article in the esteemed medical publication New England Journal of Medicine documented that infants’ lives have indeed been terminated in the Netherlands. It suggests that there have been around 600 such cases.

Asked about his views in the light of this being no longer just a thought-experiment but a reality, does Singer still think parents should, under certain circumstances, have the right to terminate the lives of infants who suffer incurable and painful diseases?

Singer’s response is measured rather than kneejerk: “The article refers to only 22 cases of active euthanasia in severely ill newborns, over seven years. The figure of 600 refers to all cases in which medical decisions led to the end of life – for example, turning off a respirator. That happens all over the world, in every neonatal intensive care unit.”

Nonetheless, there are actual cases. Can they be morally justified? Singer thinks so: “I agree with the authors of the article that there are some cases in which, if the parents agree, active euthanasia for a severely disabled newborn infant is justifiable.”

Utilitarianism

To have such views is perhaps unusual. Some would say extreme. But for Singer they are based on philosophical foundations. And Singer is unashamedly a utilitarian. John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) defined this approach to ethics in the following terms in his book Utilitarianism:

“Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness” (Utilitarianism, 1863, 4). But Singer goes a bit further back in his utilitarianism in his defence of euthanasia:

“Jeremy Bentham, the founder of the English school of utilitarians, also known as the ‘philosophical radicals’, was an early advocate of voluntary euthanasia, as he was of many other reforms that have subsequently been adopted.”

But while closer to Bentham than Mill, Singer is at pains to acknowledge the views of Mill too:

“The arguments of John Stuart Mill, in On Liberty, are also very relevant here. In addition, there is now a great deal of information about the actual practice of legal VAD that wasn’t available to anyone in a previous century.”

So far so good, but could the introduction of legal euthanasia be the start of a slippery slope? Some people have argued that Canada is an example of the unintended consequences. In that country the right to die was expanded from those with a terminal illness to others with an incurable disease. He is not concerned about that coming to Oz?

“No, the Canadian decision was not based on common law, but on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms that became law in Canada in 1982. We have nothing comparable to that [in Australia].”

Nor is he concerned that in Canada, 4.7 percent of all deaths were a result of the introduction of euthanasia. He does not see it as a high number. Far from it: “It shows that there was a previously unmet need for voluntary assisted dying”, he says.

Singer of course admits that there are philosophically-sophisticated ethical systems other than his own. A philosopher like Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) did not believe in the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people, but assessed every action according to whether it was consistent with a moral law. Singer says that, “Kant was opposed to a right to die.”

But he is not sure all Kantians would agree with the master. Kant’s philosophy was based on his famous Categorical Imperative, which states that we should “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” (Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, 166). Singer is open to the possibility that a Kantian could be in favour of voluntary assisted dying, “There are many interpretations of the Categorical Imperative, and yes, on some of them, it could be.”

But his fundamental belief is utilitarian, so it is not surprising that his defence of voluntarily assisted dying is based on utilitarianism: “Mill famously defended the view that the state should only prohibit actions that caused harm to others. A person’s own good, physical or moral, was his own business. So, Mill would have argued that VAD should be legal.”

Whether these considerations convince – or otherwise – the politicians grappling with this practical ethical question, let alone their voters, is, of course, another matter.

• Matt Qvortrup is a regular contributor to Philosophy Now.