Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Articles

Fortune-Tellers & Causation

Seán Moran won’t be palmed off by talk of backwards causation.

Giving money to fortune-tellers seems a foolish thing to do. But many clairvoyants earn a good living, so there must be enough customers with faith in their future-seeing powers to keep them in business. Of course, some of those who pay to have their fortunes told approach the experience in an ironic or amused manner, but others take the predictions seriously. And occasionally the prophecies will turn out to be correct, just by the laws of probability. As long as the palm-reader has a plausible manner and makes accurate forecasts from time to time, he can continue to ply his trade profitably.

However, it would not be a legitimate philosophical move to let customer satisfaction indicate the value of a fortune-teller’s contribution to knowledge. In fact, textbooks on epistemology (the philosophy of knowledge) typically cite clairvoyance as a prime example of ‘non-knowledge’. The classic definition of knowledge requires the knower to have a ‘true, justified belief’. The fortune-teller may sometimes unwittingly speak the truth, and may even fervently believe his own utterances, but he falls down over the matter of justification. Even if he gets it right and utters a statement that later comes true, the absence of a reliable mechanism for gaining knowledge undermines the clairvoyant’s claims to have justified knowledge about the future.

Justification usually flows from a combination of the ‘onboard’ epistemic resources of perception (of evidence), memory, and cognition, and the ‘outboard’ resource of testimony. By these means, it is possible for us to have knowledge of the past and the present, but not usually of the future. We can know things about the past by perceiving historical evidence (artefacts, photographs, and so on) and by receiving testimony (spoken, written, or electronic) from those who were present at a particular event. If we too were there at the time, we can also draw on our memories, and our presence there gives this knowledge the splendidly-named extra quality of ‘voluptuous legitimation’. (It is sometimes said of the 1960s that if you can remember them you weren’t there, so voluptuous legitimation doesn’t always help.) The last of the trio of onboard resources, cognition (thinking), enables us to piece the jigsaw together, and hence to justify our true belief.

In the present, we can similarly draw on all four epistemic sources, but perception has a particular immediacy. Were this page suddenly to burst into flames, for example, we could know this without any mnemonic, cognitive or testimonial buttressing. So direct perception can be justification enough of a belief. After the event, though, we might seek confirmatory testimony from a nearby witness – “Did you see that?” – trawl through our memory for similar happenings, and use our cognitive powers in an attempt to make sense of the event. Everyday life does not usually provoke much epistemic analysis, but out-of-the-ordinary experiences such as spontaneous combustion demand our full attention. Even then, we might not acquire genuine insightful knowledge about what happened.

Predicting the future is more precarious, but it is possible to acquire true, justified beliefs about days yet to come. I can confidently predict, for example, that Pythagoras’ Theorem will still be correct when this magazine is published. We can do this with all the truths of mathematics, for they are ‘necessary’ truths – they have to be that way in all possible situations or eventualities (worlds). In the case of ‘contingent’ truths – facts that could have turned out otherwise – predictions can still yield true justified beliefs, but with less certainty. I might know, for example, that in a few seconds’ time, a recalcitrant cricket ball will break my kitchen window even as I sit here writing this article. I can know this by observing its present trajectory and extrapolating it into the future. But a sudden gust of wind could interfere with this prediction. (The chances are that I would be right in this scenario, though.) This lack of certainty does not negate my knowledge claims, and it would be prudent to act as if my prediction were accurate, by moving away from what will shortly be flying glass. If I am outside the house, I might be able to add my contribution to the chain of events in the form of an heroic catch. We do not always act as if our reasonable predictions are true, however. If I buy a lottery ticket, the chances are extremely high that I will not win millions. Statistically, I am more likely to be struck by lightning, so I can know with a high degree of confidence that mine is not a winning ticket. I am, nevertheless, strangely reluctant to burn it.

Backwards Causation, Impossibility Of

As long as the fortune-teller confines his predictions to events whose trajectory already seems to be in progress, or which are statistically likely anyway, he can expect to enjoy some success. By gathering enough clues from his client’s demeanour, appearance and conversation, he may be able to formulate reasonable conjectures about what their future holds. It is the claim that he can somehow see the future that is philosophically untenable. If this were the case, a future event would be causing a present belief. Causation works the other way around, though: causes come first in the timeline, followed later by their effects. This phenomenon of causes preceding their effects is such a strong part of the thinking of minds like ours that Immanuel Kant in The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) rates it not just as a truth, but as a synthetic a priori truth. He means by this that causation is a truth that is not gained from experience; it is known prior to or independent of experience. In fact, for Kant it is a precondition of experience: we can only have a coherent experience of a world where effects follow causes, and we cannot imagine things to be otherwise.

But, as hard to believe as this may be, who is to say that causation cannot actually proceed in the other direction? Might the fortune-teller have unusual sensitivities that can detect the effects of future causes?

Well, no. If such backward causation really were possible, it would always be susceptible to what the British-American philosopher Max Black in 1956 called ‘bilking’. In everyday talk, bilking means defrauding someone out of money, or circumventing their right to have what is due to them. In the philosophical sense intended here, it means depriving the effect of what would otherwise be its cause. For example, if the clairvoyant tells us that we will have a boating accident, we can resolve henceforward to stay away from boats. Then the future cause could not have the claimed past effect on the soothsayer, for it will never happen: we won’t have a boating accident. This type of bilking is not possible after normal causation, for after the event both the cause and its effects are now consigned to the past, safe from attempts to change them. If I see a ball smash my kitchen window, I cannot retrospectively interfere with this causative sequence. It is too late for that, once the light from the broken window has reached my retina. (If I notice the ball en route, that’s a different matter, as we have already seen). The cause of the sensory effect has already occurred and cannot be revoked. But revoking the cause is, in principle, available to us in the case of any apparent retro-causation, such as that which clairvoyants claim. Because the cause is in the future, it is possible to interfere with it, and hence give the lie to their predictions. That is to say, if the clairvoyant says nothing, his secret predictions might come true. Once he tells his ‘victim’, though, she can attempt to avoid her predicted fate, and make his predictions wrong from the start. That is, as long as she is not taken in by his fatalism and doesn’t resign herself to the view that ‘whatever will be will be’.

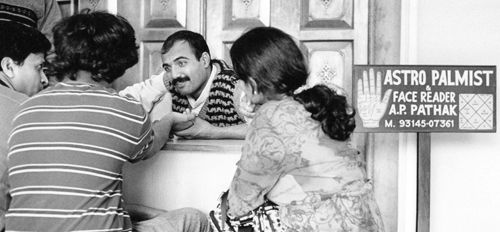

Palmist in Rajasthan, India. Photo © Seán Moran 2013

Causes & Motivations

Despite this bilking argument, it does sometimes appear as if the future has a causative effect on the present. For example, the desire for a future event can cause us to act in certain ways. However, it is a present desire that causes the action: the prize is the effect of the hard work that preceded it, not the physical cause of it. It is incoherent to say that the future passing of an exam is the physical cause of the hours of revision that led up to it. The desire to pass the exam might have been our motive, but the physical causation runs the other way. Our diligent revision caused the exam success.

If we accept the bilking argument, it is clear that fortune-tellers’ intuitions cannot be caused by future events, so they have no good epistemic justification for their pronouncements. But to stay in business they merely need excellent interpersonal skills, not epistemic credibility. The palmist in my photograph is typical of others I have observed: he makes good eye contact, holds hands with his client, listens intently (to pick up cues that can be used to make predictions), and shows concern. We might think that the experience is harmless – benign even – but the interaction can be fundamentally disempowering. By making his client think in fatalistic ways, he may well prevent her from taking action to circumvent undesired possibilities, or he may discourage her from working towards her goals, because they will only happen if they are ‘meant to happen’.

Our analysis has been rooted in notions of cause and effect, but the only causal chain that the clairvoyant is really involved in here is causing vulnerable people to give him money. Maybe this is unfair, though. Perhaps to be convincing, the fortune-teller must first convince himself that he has the gift of prophecy. Only by deluding himself can he delude his clients.

© Dr Seán Moran, 2013

Seán Moran is a philosopher at the Waterford Institute of Technology, Ireland. In his spare time he uses vintage Leica cameras to photograph life on the streets.