Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

The Self

The Illusion of the Self

Sam Woolfe says that we’re deluding our selves.

In our day-to-day lives, it always appears that there is an I who is thinking, perceiving, and interacting with the world. Even the language we use assumes that there is a self – a distinct conscious entity: when we talk to each other we say, ‘I think…’, ‘You are…’ etc. However, appearances can be deceptive. The cognitive scientist Bruce Hood defines an illusion as an experience of something that is not what it seems. He uses this definition in his book, The Self Illusion: How The Social Brain Creates Identity (2012), arguing that the self is an illusion – and he admits that everyone experiences a sense of self – a feeling that we have an identity, and that this identity does our thinking and perceiving – but he says that beyond the experience, there is nothing we can identify as the self.

In The Principles of Psychology (1890), William James said that we can think of there being two kinds of ‘self’. There is the self which is consciously aware of the present moment – we represent this self by using the pronoun ‘I’; then there’s also the self we recognise as being our personal identity – who we think we are – which we represent by using the term ‘me’. According to Hood, both of these selves are generated by our brain in order to make sense of our thoughts and the outside world: both ‘I’ and ‘me’ can be thought of as a narrative or a way to connect our experiences together so that we can behave in an biologically advantageous way in the world.

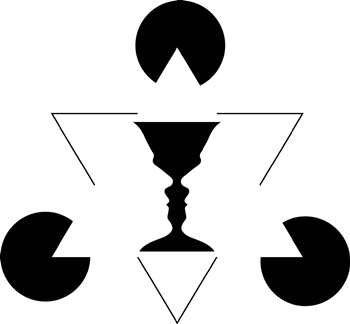

A helpful way to understand how the brain creates the illusion of the self is to think about perceptual illusions such as the Kanizsa triangle [see illustration]. In this illusion we see a triangle even though no triangle has been drawn, due to the surrounding lines and shapes giving the impression of there being a triangle. Our brain essentially ‘fills in the gaps’. Hood states that our sense of a self is similarly a hallucination created through the combination of parts. We perceive the self as a result of different regions in our brain trying to combine our experiences, thoughts, and behaviours into a narrative, and in this sense the self is artificial.

Hood’s argument is that our brain naturally create narratives in order to make sense of the world. Essentially, our brains are always thinking in terms of stories: what the main character is doing, who they are speaking to, and where the beginning, middle, and end is; and our self is a fabrication which emerges out of the story-telling powers of our brain.

This belief has been backed up by case studies in neurology. For example, in many of his books, neurologist Oliver Sacks describes patients who suffer some damage to a memory region of their brain, and they literally lose a part of themselves. In Dr Sacks’ best-known book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat (1985), he describes a patient known as Jimmy G who has lost the ability to form new memories and constantly forgets what he is doing from one minute to the next. (In the film Memento, the protagonist suffers from the same condition.) Due to this condition, however, Jimmy has also almost lost his sense of self, since he cannot form a coherent narrative of his life. This loss of narrative is deeply troubling, and means Jimmy struggles to find meaning, satisfaction, and happiness. Cases like this show not only that the sense of self depends on a multitude of brain regions and processes, but that our happiness depends on the illusion of self.

Other evidence from neuroscience supports the claim that the brain is a narrative-creating machine. Dr Sacks reports many different patients who make up stories to explain their impairments. The neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran also recounts patients who are paralysed but who deny that they have a problem. The brain is determined to make up stories even in the face of obvious and compelling evidence (e.g. that an arm will not move).

This does not mean that the illusion of the self is pointless. It is the most powerful and consistent illusion we experience, so there must be some purpose to it. And in evolutionary terms, it is indeed useful to think of ourselves as distinct and personal. There is more of an incentive to survive and reproduce if it is for my survival, and my genes remain in the gene pool. After all, how can you be selfish without a sense of self? If we had no sense of self, and we perceived everything as ‘one’ or interconnected, what would be the point of competition? Perhaps then some important moral lessons can be drawn from the fact that the self is artificial, a construct.

The idea that the self is an illusion is not new. David Hume made a similar point, saying the self is merely a collection of experiences [see box in Chris Durante’s article]. And in early Buddhist texts the Buddha uses the term anatta, which means ‘not-self’ or the ‘illusion of the self’. Thus Buddhism contrasts to, for example, Cartesianism, which says that there is a conscious entity behind all of our thoughts. The Buddha taught his followers that things are perceived by the senses, but not by an ‘I’ or ‘me’. Things such as material wealth cannot belong to me if there is no ‘me’, therefore we should not cling to them or crave them.

© Sam Woolfe 2013

Sam Woolfe is a philosophy graduate from Durham University. He is a writer and editor at The Backbencher magazine and blogs at www.samwoolfe.com. He lives in London.