Your complimentary articles

You’ve read one of your four complimentary articles for this month.

You can read four articles free per month. To have complete access to the thousands of philosophy articles on this site, please

Brief Lives

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

Daphne Hampson on the man many consider to be the father of existentialism.

Søren Kierkegaard, the Danish thinker the bicentenary of whose birth we celebrate this year, was suspended between two worlds. On the one hand in the face of the Enlightenment – with its devastating implications for classical Christianity, which had led others to try to adapt the faith – he would point to Christian claims. On the other hand he too was a child of the Enlightenment and Romanticism. In pursuit of the question as to what it would mean to be Christian within modernity Kierkegaard created a fascinating and far-flung body of work, employing a novel and flamboyant literary style which would affect twentieth century literature, theology and philosophy.

Life and Work

Born in 1813, Kierkegaard undertook the major part of his work during a mere seven years (1842-49) in his thirties. Having come from an evangelical background, his reading during his student years led him to a point where the veracity of Christian claims was called into question. His early work would represent a dialogue between a Christian position and an Enlightenment, or Kantian, position; the devil being Hegel who, translating transcendence into immanence in the unfolding of history, had confused the two. Kierkegaard’s polemic was directed against Danish Hegelians and a church that had reduced Christianity to a Christianised culture.

In Fear and Trembling (1843) Kierkegaard pits Abraham, who will obey the command of God, if necessary slaughtering Isaac his son, against the Kantian presupposition that there can be no higher calling than the ethical imperative. Kant, too, had considered the akedah (the story of the binding of Isaac, Genesis 22), in a passage Kierkegaard must have known. Hegel muddies the water. Likewise, in Philosophical Fragments (1844), Kierkegaard contrasts the Socratic (and Enlightenment) position, in which all truth is inherent to the learner (and we may supplement this by saying also that truth which is given with the world), with the Christian claim that ‘Truth’ (of a different order) was ‘given’ to humankind at a particular moment in history, making Christianity what Kant rightly called a ‘historical’ religion.

Kierkegaard’s presuppositions here derive from the eighteenth century. Following Leibniz’s distinction between absolute and historical truths, Lessing had spoken of the “wide, ugly, ditch” that prevents a deduction of the absolute (God) from the contingencies of history (the man Jesus Christ). Kierkegaard is in accord. But he will seek to cross the ditch by a subjective movement of ‘faith’, which throws a line across to the objective ‘Truth’ which is the Chalcedonian confession (AD 451) that Christ is both divine and human in one persona (or entity). Kierkegaard hopes to validate Christian faith in the face of a Feuerbachian reductionism (counting it a human projection), newly on the scene.

In a work of two years later, the so-called ‘Postscript’ to Fragments, Kierkegaard cashes out in existential terms what it is to be a human being who, in each moment, while finding his identity in pursuing “the thought of eternal life” occupies himself with this or that. It is to such writing that the existentialists were to owe so much, as Kierkegaard considers the human propensity to lose oneself amid the trivia of our lives. Thus he delineates the different ‘stages’ or modes of life (aesthetic, ethical, and potentially religious) in which human existence can be framed. His target is ‘Christendom’, a world in which Christian faith has lost its edge, transmuted without remainder into mere civilised living.

Concurrently with Fragments, Kierkegaard published a much different, phenomenological, exposition, The Concept of Anxiety. Kant, Hegel and the great theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher had all considered ‘Adam’ more or less a mythical figure. Lutheran tradition conjectured a ‘positive’ freedom (freedom understood as identity with God), while the disobedience of the Fall represented separation and a concomitant anxiety. Schelling had faced the same dilemma as Kierkegaard: how to validate human independence, choice and creativity, while acknowledging the human need for God. The context, further, is that as to how to recast the conception of ‘original sin’ given the dawning recognition of evolution and thus of there having been no Fall. Kierkegaard produces a remarkable work, plumbing the depths of human subjectivity.

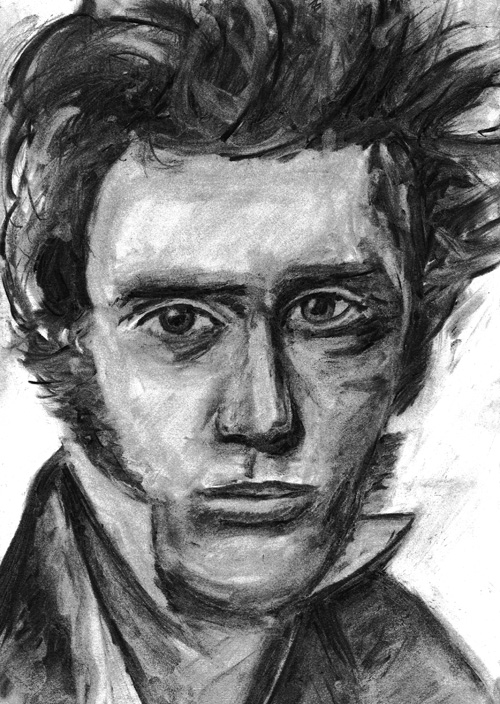

Portrait of Kierkegaard © Athamos Stradis 2013

In Works of Love – or, better translated, Love’s Deeds – (1847), Kierkegaard gives us a beautiful book, again of a whole different genre (as indeed he published edifying discourses throughout these years). As God loves us agapeistically (unconditionally, irrespective of our merits) so are we called to love our neighbour. The book is a strange composite of compassion for others, evincing deep insight into human relations, together with social views that must make us cringe. Thus Kierkegaard thinks a beggar should make himself scarce lest his presence disturb others’ faith in God’s goodness; a stance that was to outrage among others Theodor Adorno. But Kierkegaard was not callous. The world for him has become a ‘meanwhile’ in light of God’s eternity, while before God humans enjoy a fundamental equality.

The revolutionary year 1848 brought Kierkegaard to a new pitch of intensity, bequeathing us some of his most remarkable work. A monarchical conservative, Kierkegaard disdained in equal measure the patriotic fervour whipped up against Germany in the dispute over Schleswig-Holstein and the strident call for a new political order. His response to what he judged mass hysteria was, as he said, to make ‘his category’ that of ‘the individual’, focussing in his writing on the self in its relation to God. In The Sickness Unto Death (1849), a book about healing, he conceives of the self as self-reflexive (as had Hegel), but for Kierkegaard the synthesis of body and spirit (or mind) which is the self can only come about as one “rests transparently in God”; a very Lutheran insight.

Kierkegaard’s post-Enlightenment recognition that we must be said to come into our own, in his case not only in relation to others but to God, while concomitantly finding God fundamental to the self’s composition, makes his subtle conceptualisation of the self perhaps the finest in Christian tradition. Later work was to take on board an almost Augustinian sense (more commonly found in Catholicism) of progress in becoming oneself as the self is drawn in love to God. It is brilliant, sensitive, deeply spiritual writing. Nevertheless such a conception carries as a corollary problematic questions pertaining to one’s relation to the world, more particularly to women. Kierkegaard has become the lover of an anthropomorphically conceived God in substitution of her.

In his final months Kierkegaard provoked a head-on collision with the Danish state church, charging that it had lost all sense of the ‘otherness’ and demands of Christianity. True discipleship, said Kierkegaard, far from conforming to the world, was liable to lead to martyrdom. In Practice in Christianity (1850) he had thrown down the gauntlet, castigating the esteemed Primus of the Church, J.P. Mynster and the social mores he represented. Now Kierkegaard, founding his own broadsheet, addressed the populace at large. It was in particular (as had been the case in the earlier debate over Hegel) the succeeding Primus H.L. Martensen, who called forth his ire. The struggle still in full spate, Kierkegaard died, aged 42; a death he conceived of as ‘martyrdom’ for the cause.

Influence and Significance

Kierkegaard’s influence has been extraordinary, traversing diverse disciplines. Writing in a minor European language, and perhaps also on account of having fallen out with his peers, the impact of his thought took time to materialise. But Kierkegaard was influencing German scholarship by the 1920s, French by the 1930s, his influence becoming global through translation into English in the 1940s. Today he is available in languages from Korean to Hungarian. (I found his work in a bookshop on the seafront promenade in Lima, Peru.) While he predicted he would be “translated into other languages”, Kierkegaard would have been incredulous!

In philosophy Kierkegaard’s work played a seminal role in that broad movement of thought known as ‘existentialism’. Heidegger was to acknowledge Kierkegaard’s masterly exploration of the human condition as one of ‘Angst’. Governed by contingency, yet in spirit soaring above the world, the human being finds himself torn asunder. He must come into his own within his situation of ‘thrownness’ (Geworfenheit) in the world, facing death. Partly through Heidegger, but also directly, Sartre likewise came under Kierkegaard’s sway. His depiction of the human state as tossed between what it is to be pour soi(‘for itself’, creative yet anxious) and en soi (‘in itself’, content but inert) reflects the Kierkegaardian (and ultimately Lutheran) disjuncture between independence and identity.

Kierkegaard’s ‘stages’ are well captured by Albert Camus’ novel The Fall. The protagonist lives the ‘aesthetic’ life as, in a bar in foggy Amsterdam amidst the pimps and prostitutes, he conspires to lose his ‘self’. We learn however that he had formerly been a Paris lawyer, living the life of ‘ethical’ respectability. Witnessing a young woman throw herself into the Seine, and hurrying by, he was forced to recognise the farce that was his self-congratulatory existence. (Compare Kierkegaard in Either/Or, 1842): “Forget… that there was piety in your soul and innocence in your thought… doze your life away in the glittering inanity of the soirées, forget that there is an immortal spirit within you; and when wit grows mute there is water still in the Seine.”) Jean-Baptiste (significantly his name) keeps in a cupboard the stolen panel of the Van Eyck triptych depicting the just judges ‘on their way to meet the lamb’. Penitence and entry into the ‘religious’ sphere remain an open possibility, but in the final line “it will always be too late”.

Kierkegaard’s pervasive influence has thus been through the use of literary writing to convey philosophical truths pertaining to human living. He showed astutely (perhaps in this influenced by ancient Greece) that fundamental questions of life and values might best be illuminated not in the abstract but through consideration of the concrete nature of human living in its everydayness. His writing is witty, imaginative, versatile and always highly perceptive as, through the many characters of his creation, he depicts the foibles of humanity and the frequent tragedy of life, if also the greatness of human beings and sublimity of the human condition. If constrained necessarily by our contingency, the world is yet wide-open. Kierkegaard invites us to choose, in the first place, ourselves.

Kierkegaard judged himself the greatest prose writer his native tongue has known – and his fellow Danes have not dissented. Much must inevitably be lost in translation, yet the reader can gain a sense of the beauty and rhythm of his prose, most notably in his prayers. Kierkegaard writes in such a way as to draw the reader in; not cajoling, but simply illuminating the options. In later work however, as his own circumstances darken, a bitterness creeps in. It is difficult to square his sour condemnation of those who fail to believe the Paradox of the God/man with his own high standards of behaviour and conduct (and indeed with what may well have been a personal hope that all will be saved). But Kierkegaard was following what he believed to be the letter of the biblical text.

Kierkegaard begat existentialism

Unsurprisingly, Kierkegaard was a major influence on twentieth century so-called ‘dialectical’ (Barthian) theology, following Karl Barth. If, subsequent to the Enlightenment, in particular the constrictions of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, it was no longer possible to reason one’s way to God, and if Schleiermacher’s attempt to found theology in the immediacy of religious awareness should be judged deficient (as both Hegel and Kierkegaard contended) then the only alternative was a revelation “straight down from above” as Barth, acknowledging Kierkegaard’s influence, was to put it in his revolutionary 1922 Epistle to the Romans. In Fragments, the God who is Christ both is the ‘Truth’ that is revealed and himself brings as gift to the disciple the condition of its recognition. Theology becomes self-contained (or circular).

The young Dietrich Bonhoeffer was also deeply influenced, the title of his 1936 The Cost of Discipleship (in German Nachfolge, the one word having the double entendre of ‘consequences’ and ‘discipleship’) culled from the entry on Kierkegaard in a German encyclopaedia. As his life played out in the church struggle amid the circumstances of the Third Reich, Bonhoeffer found inspiration in Kierkegaard’s witness. But the problems with a Kierkegaardian position also become evident. Bonhoeffer’s Christology (compiled after his death from students’ notes taken at his 1933 lectures), prefaced incidentally by a quotation from Kierkegaard, “Be silent for that is the infinite” advocates precisely Kierkegaard’s ‘leap of faith’ in acknowledgment of the Paradox that is Christ. To speak in this manner reflected the times; it was a confession that provided a frontal challenge to the ‘leap of faith’ that many were making to Hitler. But such thinking does not axiomatically lead to talk of human rights or an advocacy of humanistic values per se.

Of recent years Kierkegaard’s writings have met with a ready reception among post-modernists. His playing with words and styles of writing, his quirky outsider’s readiness to demolish the verities of his age, and the proliferation of pseudonyms in what has been called polyphonic writing, have made him an ideal candidate as the Ur-father of a certain manner of writing. But in Kierkegaard’s case these traits can also lend an inconsistency to the authorship (not least in the question as to whether talk of God should commence from a revelation given ‘straight down from above’, or whether the human movement to Christianity finds a starting point in human anxiety, to which revelation provides the answer. As regards Kierkegaard’s use of pseudonymity, it should be noted that it was a common practice in his society: there is little divergence of viewpoint from his private journals; and it is evident that the decision to employ a pseudonym was frequently last minute.

What strikes me as deserving of attention – as we celebrate the bicentenary – is the revolution in presuppositions that, in every sphere, at least European society has undergone. Kierkegaard may credit Incarnation through faith, and not on account of reason, but nevertheless his belief stands within a field populated by presuppositions about knowledge that serve in his day to make it ‘thinkable’. Living a hundred and fifty years after Newton, Kierkegaard betrays little recognition that there can be no one-off exceptions to, or breaks in, the chain of cause and effect. He is, accordingly, a ‘supernaturalist’, crediting miracles. Again in this at one with his age, he conceived history to have a telos or goal, believing that, acting through interventionary events, God is bringing his purposes to fruition. Kierkegaard conceptualised the human as a synthesis, brought about in the moment, of spirit and carnal nature (in parallel to the Incarnation). Politically and socially too Kierkegaard is a man of his time, failing to conceive that social engineering could mitigate the lot of the poor, and thinking women ordained to be subordinate and obedient to men.

The fascination of studying a past writer of Kierkegaard’s magnitude and perspicacity is that one may chart in history the progress of the human spirit. One is brought to recognise the crucial nature of the material and scientific context within which our thinking occurs. Writing as recently as the 1840s, Kierkegaard thinks within the confines of a comparatively limited world: having little awareness of non-Eurocentric cultures; conceiving that there must have been an original human pair (for, as he says, nature “does not favour a meaningless superfluity”); and with no notion of the timescale or size of the universe. Most strikingly, human beings possess for him a certain divinity, a conceit perhaps irrevocably lost with Darwin. Kierkegaard belongs to a thought-world, stretching from Plato, in which a belief in the beyond inflects all his thinking. Most damagingly, in scholarship already underway in his age, the scriptures have today been set within the cultural context of their composition. Yet, for all this, Kierkegaard’s writing retains a freshness that never ceases to yield new insights and food for thought.

© Daphne Hampson 2013

Daphne Hampson holds doctorates in history from Oxford, in theology from Harvard, and a master’s in continental philosophy from Warwick. Professor Emerita in Divinity at St Andrews, she is an Associate of the Department of Theology and Religion at Oxford. She is the author, among other works, of Christian Contradictions: The Structures of Lutheran and Catholic Thought (Cambridge University Press, 2001) and of Kierkegaard: Exposition & Critique (Oxford University Press, 2013).